When I was a kid, my mother sometimes threatened to give my brother and I pronunciation lessons. We all know that in a class society like Britain, how you speak matters a lot. Our increasingly diverse hometown of Peterborough was prosperous enough, but not posh. Six in 10 of the city's residents voted for Brexit, serving as a reverse indicator of the upper classes. (Thursday's general election gave Peterborough its first Labour MP since 2001.)

My mother came from a working-class rural background and wanted us to rise up the social ladder without having to worry about a false accent. We never ended up taking pronunciation lessons, but we did have to attend Saturday morning ballroom dancing lessons, and she didn't want us to fail there either.

In the end, my brother and I got along well, thanks to the stable, loving, middle-class home we grew up in. Any remaining working-class vestiges of my own accent were wiped away by three sanitized years at Oxford. My wife says it comes back when I drink, but she doesn't know what she's talking about. She's American.

I’ve always found British classism depressing, which is one of the reasons we brought our British-born sons to America, where class is a quaint thing, something you can observe with amazement through imported TV shows like “Downton Abbey” and “The Crown.”

So imagine my horror when I discovered that the US is more rigidly classed than the UK, especially at the top. The big difference is that in the US, most of the people at the very top deny their privilege. The US myth of meritocracy allows them to attribute their status to their own talent and hard work, rather than luck or a rigged system. At least upper-class people in the UK have the decency to feel guilty.

In the UK, it is politically impossible for a prime minister to send his children to the equivalent of a private high school; not even Eton-educated David Cameron could do it. In the US, even the most liberal politicians can fund a luxury private education. Some of my most progressive friends send their kids to $30,000-a-year high schools. It's not that they do it that's surprising; it's that they do it without any moral qualms.

America's class reproduction machine operates with ruthless efficiency beneath its classless surface. The upper middle class in particular is strengthening. This privileged stratum of the income distribution, with an average annual income of $200,000, is separating itself from the bottom 80 percent. Overall, pre-tax incomes for this top fifth have increased by more than $4 trillion since 1979, while everyone else's income has remained at just over $3 trillion. Some of this growth has gone to the top 1 percent, but most of it has gone to the 19 percent just below them.

The “we are the 99 percent” rhetoric is actually dangerously self-serving, allowing people with healthy six-figure incomes to convince themselves that they are somehow in the same economic situation as ordinary Americans and that the so-called ultra-rich are to blame for inequality.

While politicians and policy experts worry about poverty continuing through generations, wealth is more strongly inherited. Most disturbing is the realization of just how firmly class status is passed down through generations: Most children born into the top 20 percent of families stay there or drop only to the next fifth. As Gary Solon, one of the leading scholars of social mobility, recently said, “Rather than a poverty trap, there seems to be more persistence on the other side of it: a 'wealth trap,' so to speak.”

There's a kind of class doublethink going on here: on the one hand, upper-middle-class Americans believe they operate in a meritocratic society (the belief that they are entitled to what they've earned), and on the other, they constantly engage in anti-meritocratic behavior to benefit their own children. To the extent that ethical considerations are raised, they usually end up with the justification, “well, it may be wrong, but that's what everyone does.”

For example, the United States is the only country where it's easier to get into college if one of your parents went to college. Oxford and Cambridge abolished the practice in the middle of the last century. It's surprising that such an unfair practice exists in 21st-century America. But what strikes me even more is how comfortable even supposedly upper-middle-class liberals seem to be in taking advantage of it.

Upper-middle-class people also do a lot of things right by creating stable home environments and being actively involved parents. This behavior should be encouraged, not discouraged. Working hard to raise good children shouldn't be seen as a bad thing.

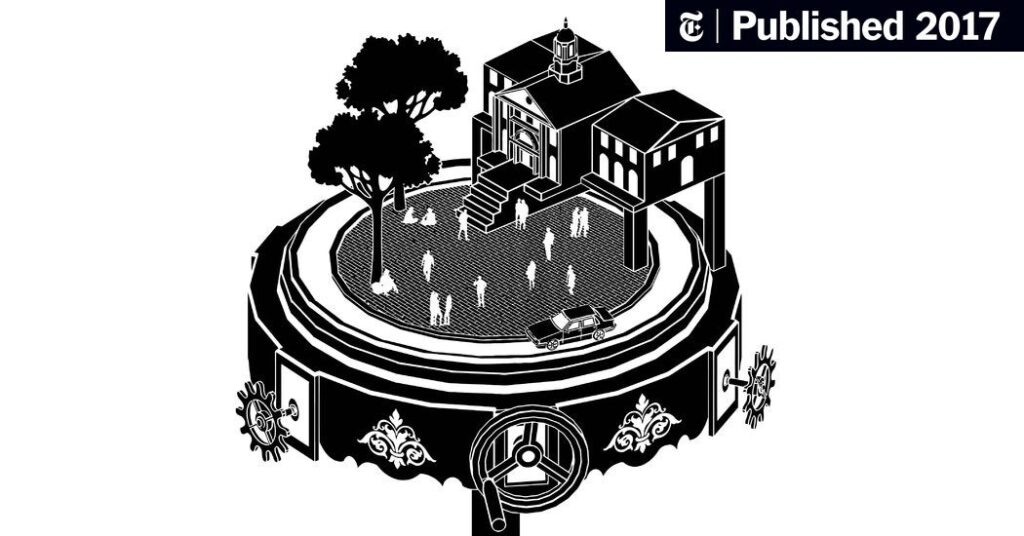

But when the upper-middle class starts manipulating markets to their own advantage, to the detriment of others, things get ugly. Take housing as perhaps the most important example. Exclusionary zoning practices allow the upper-middle class to live in enclaves; de facto gated communities, even if there is no gate in sight. The physical segregation of upper-middle-class neighborhoods is reflected in the classrooms, because schools typically draw students from the surrounding areas. Good schools make neighborhoods more desirable, further increasing home values. The federal tax code gives us a handout to help buy these expensive homes, through the mortgage interest deduction. For the upper-middle class, regardless of their professed political orientation, zoning, wealth, tax credits, and educational opportunity reinforce each other in a virtuous cycle.

It takes courageous politicians to question the privileges enjoyed by the upper-middle class. Recent attempts to make zoning laws more inclusive have failed in liberal cities like Seattle and states like California and Massachusetts. Mortgage interest subsidies seem to be an immortal deduction (in contrast to the UK, where equivalent tax breaks were phased out by 2000 under both Conservative and Labour governments).

Or 529 college savings plans, another waste of money: a tax-free way to put money aside for education expenses. Thanks to a law signed by George W. Bush in 2001, capital gains on these plans are exempt from federal taxes. Most states allow you to deduct savings up to a certain amount from your state income tax. The benefits of 529 plans go almost entirely to middle-class and above-class families. But when President Obama proposed eliminating the federal tax credit in 2015, there was uproar, and not just from Republicans. Liberal Democrats representing wealthy districts roundly rejected the idea.

Progressive policies — urban planning, school admissions, tax reform — too often run up against upper-middle-class opposition. Selfishness is natural. But those who make up America's upper-middle class don't just want to maintain their advantage; they believe they deserve it, armed with a belief in a classless meritocracy. The top 20 percent exude a strong whiff of entitlement that is felt by everyone else.

Now we can see that there is an important silver lining to British class consciousness. We can see, at the very least, that class is a reality of social life. Upper-class Britons tend to see their status as at least partly the result of good fortune. For Americans to solve the problem of deepening class divisions, we must first acknowledge their existence and our own complicity in maintaining them. We need to become more aware of class. And, yes, I'm looking at you.