Gary, 2007 Rivlin is The New York Times A feature article on Silicon Valley's most successful people. One of them, Hal Steger, lived with his wife in a million-dollar house overlooking the Pacific Ocean. Their net worth was about $3.5 million. Assuming a reasonable 5% return, Steger and his wife were in a position to cash out, invest their capital, and after one glorious year, comfortably live off a passive income of about $175,000 per year for the rest of their lives. But, Rivlin writes, “Most mornings, [Steger] “By 7 o'clock I'm at my desk. I usually work 12 hours a day, plus an extra 10 on weekends.” Stöger, then 51, noticed the irony (sort of). “People from the outside looking in ask why a guy like me keeps working so hard,” he told Rivlin. “But a few million dollars doesn't make you what it used to.”

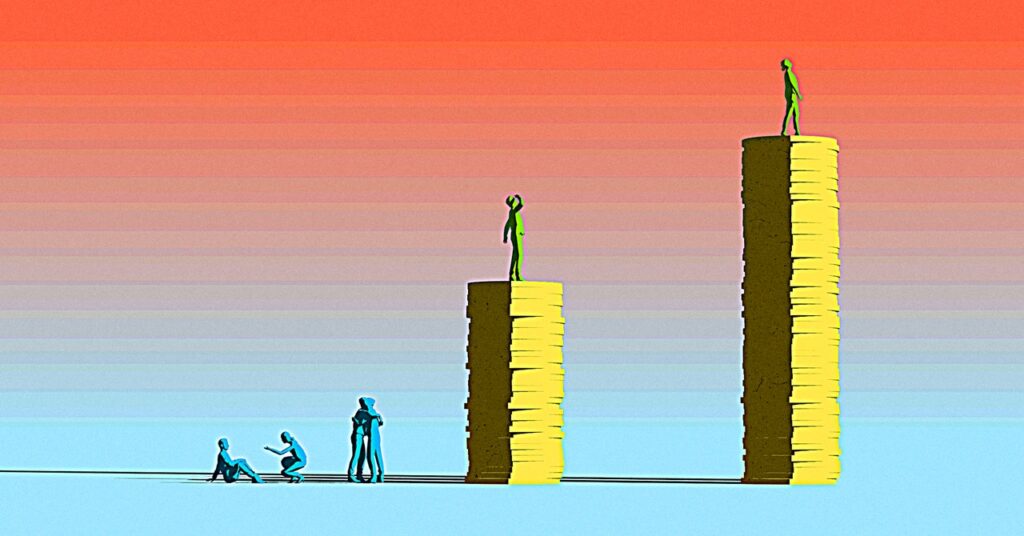

Steger was probably referring to the damaging effects of inflation on currency, but he seemed oblivious to how wealth was affecting his psyche. “Silicon Valley is full of what you might call working-class billionaires,” Rivlin wrote. “Hardworking people like Steger continue to work surprisingly hard, even when they realize they are among the lucky few. But many of these successful and ambitious members of the digital elite don't see themselves as particularly lucky, in part because they are surrounded by others who are richer, often much richer.”

After interviewing several executives for the article, Rivlin concluded that “people with millions of dollars often view their accumulated wealth as insignificant, reflecting their modest status in a new Gilded Age in which hundreds of thousands of people have accumulated much greater amounts of wealth.” Another notable example is Gary Kremen. The founder of Match.com, with a net worth of about $10 million, Kremen understood the trap he was falling into. “Everybody here looks at the people above me,” he says. “At $10 million, you're a nobody here.” If you have $10 million and you're a nobody, what's the price of celebrity?

Now, you might be thinking, “Screw those guys and the private jets they flew on.” That's fair. But the thing is, they're shit. Seriously. They've worked so hard to get where they are, and they've acquired more wealth than 99.999% of the people who've ever lived, but they still aren't where they think they should be. Without a fundamental change in how they approach life, they'll never reach their ever-distant goal, and even when they do realize the futility of their situation like a dark sunrise, they're unlikely to receive any sympathy from their friends and family.

What if most rich bastards are made, not born? What if the ruthlessness so common among the upper classes, the so-called “rich bastard syndrome,” isn't the result of a resentful nanny, or one too many sailing lessons, or one too many caviar meals, but a combination of disappointments and unfulfilled good fortune? We're taught that the person with the most toys wins, and that money represents points on life's scoreboard. But what if that platitude is just another side of the scam we're all caught up in? all Are you being fooled?

Spanish words Eisler “Isolation” means both “to isolate” and “to isolate,” and most people do it when they get more money. They buy a car so they don't have to take the bus. They move from an apartment with noisy neighbors to a walled-in house. They stay in expensive, quiet hotels instead of the funky guesthouses they used to frequent. They spend money to protect themselves from risk, noise, and inconvenience. But that isolation comes at the cost of isolation. For comfort, they must protect themselves from chance encounters, new music, unfamiliar laughter, fresh air, and casual interactions with strangers. Researchers have concluded time and again that the single most reliable predictor of happiness is feeling integrated into a community. In the 1920s, about 5% of Americans lived alone. Today, more than a quarter live alone, the highest level ever, according to the Census Bureau. Meanwhile, antidepressant use has increased more than 400% in the past 20 years, and painkiller abuse is epidemic. While correlation doesn't prove causation, these trends are not unrelated, and it may be time to ask some unashamed questions about our previously unquestioned desires for comfort, wealth, and power.

I was in India For the first time, I realized I was a rich bastard, too. I had been traveling for months, ignoring beggars as best I could. Living in New York, I was used to deflecting attention from desperate adults and psychopaths, but I had a hard time getting used to the group of kids who would gather right next to my table at a streetside restaurant, glaring hungrily at the food on my plate. Eventually a waiter would come and shoo them away, but they would run out into the street and keep watching, waiting for me to leave his protection and bring them some leftovers.

In New York, I had developed psychological defenses against the desperation I saw on the streets. I told myself that there were social services for the homeless, that they would buy drugs and booze with my money, that they probably got into this situation on their own. But none of this worked for these Indian kids. There were no shelters to take them in. I saw them sleeping on the streets at night, huddled together like puppies for warmth. They had no intention of using my money recklessly. They didn't even ask for money. They eyed my food like starving creatures, and their emaciated bodies were cruelly obvious evidence that they were not faking their hunger.

On a couple of occasions, I bought a dozen samosas to share, only to have the food disappear quickly as more children (and, often, adults) surrounded me, reaching out, touching, making eye contact, pleading. I knew the numbers. The money I spent on a one-way ticket from New York to New Delhi could have saved a few families from generations of debt. The money I spent at a New York restaurant the previous year could have put some of those kids through school. The budget I had set aside for a year's travels through Asia could have probably saved a few families. built school.

I'd like to say I did those things, too, but I didn't. Instead, I developed the psychological scar tissue I needed to ignore the situation. I learned to stop thinking about things I could have done but knew I wouldn't. I stopped using facial expressions that suggested I was capable of compassion. I learned to walk past dead or sleeping bodies without looking down. I learned these things because I had to, or at least told myself to. Textbook RAS.