Get our FREE US Election Countdown newsletter

Important news about money and politics in the race for the White House

Would you rather live in a society where the rich are incredibly wealthy and the poor are very poor, or a society where the rich are simply very wealthy and those with the lowest incomes enjoy a decent standard of living?

For all but the most ardent free-market libertarians, the answer is likely to be the latter. Surveys consistently show that while most people would like some distance between the top and bottom, they would actually prefer to live in a society that is significantly more equal than we have today. Many would even choose a more equal society if the overall pie was smaller than in a less equal society.

With this in mind, one good way to evaluate which countries are better places to live than others is to ask yourself, “Is life there good for everyone, or only for the wealthy?”

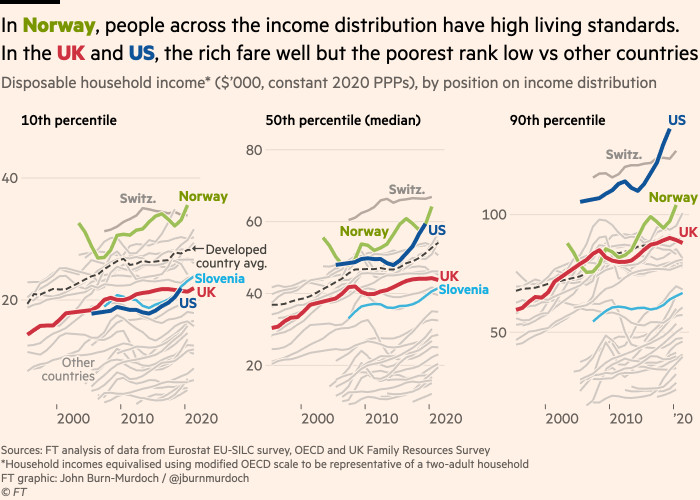

To find the answer we need to look at how people at different points on the income distribution compare to their peers elsewhere. If you're a proud Brit or American, you might want to look away right now.

At the top of the ladder, Brits enjoy a very high standard of living by virtually any standard. Last year, the top 3% of British households had about £84,000 each after tax, which equates to $125,000 after adjusting for price differences between countries. This puts Britain's highest earners well within the global elite, just behind the wealthiest Germans and Norwegians.

So what happens when you go down the scale? In Norway, the picture is consistently rosy. The living standards of the top 10% are second among the top 10% of all countries. The median Norwegian household is second among all countries. And at the other end, the poorest 5% in Norway are the richest 5% in the world. Norway is a good place to live, whether you're rich or poor.

The UK is a different story: its top earners rank fifth, while the average household ranks 12th and the poorest 5% rank 15th. Far from narrowing the gap with Western Europe, the lowest-income UK households lived 20% worse than those in Slovenia last year.

The story is similar for the middle class: in 2007, the average British household was 8% poorer than its counterpart in northwestern Europe; since then, the deficit has ballooned to a record 20%. If current trends continue, the average Slovenian household will be better off than the average British household by 2024, and the average Polish household will be even better off within a decade. Countries in desperate need of migrant workers may soon be forced to ask newcomers to take wage cuts.

On the other side of the Atlantic, the story is similar, but even worse: The rich in the United States are extraordinarily wealthy: the top 10% have the highest disposable income in the world, 50% higher than the richest in the UK. But the bottom 10% struggle with a worse standard of living than the poorest people in 14 European countries, including Slovenia.

Specifically, the US data shows broad-based growth and and Equal distribution of benefits is important for well-being. Healthy growth in living standards across the distribution in the US in the five years before the pandemic lifted all boats, but this trend was notably absent in the UK.

But redistributing the gains more evenly would make a much bigger difference to the quality of life for millions of people. Rapid growth has increased the incomes of the bottom 10% of American households by roughly 10%. But if we applied Norway's inequality gradient to the United States, the poorest 10% of Americans would see an additional 40% increase in income, while the top 10% would remain wealthier than the top 10% of almost every country on earth.

Our leaders rightly aim for economic growth, but to ignore concerns about the distribution of decent living standards, which income inequality essentially measures, shows a lack of interest in the lives of millions of people.Unless these inequalities are reduced, the UK and the US will remain poor societies with a wealthy minority.

To compare with other countries, use the interactive version of the graph below.

john.burn-murdoch@ft.com

Follow

Responses to this article:

Poverty analyses underestimate the problem / Steve New, Associate Professor of Operations Management, Said Business School, University of Oxford, UK, Fellow at the University of Hertford