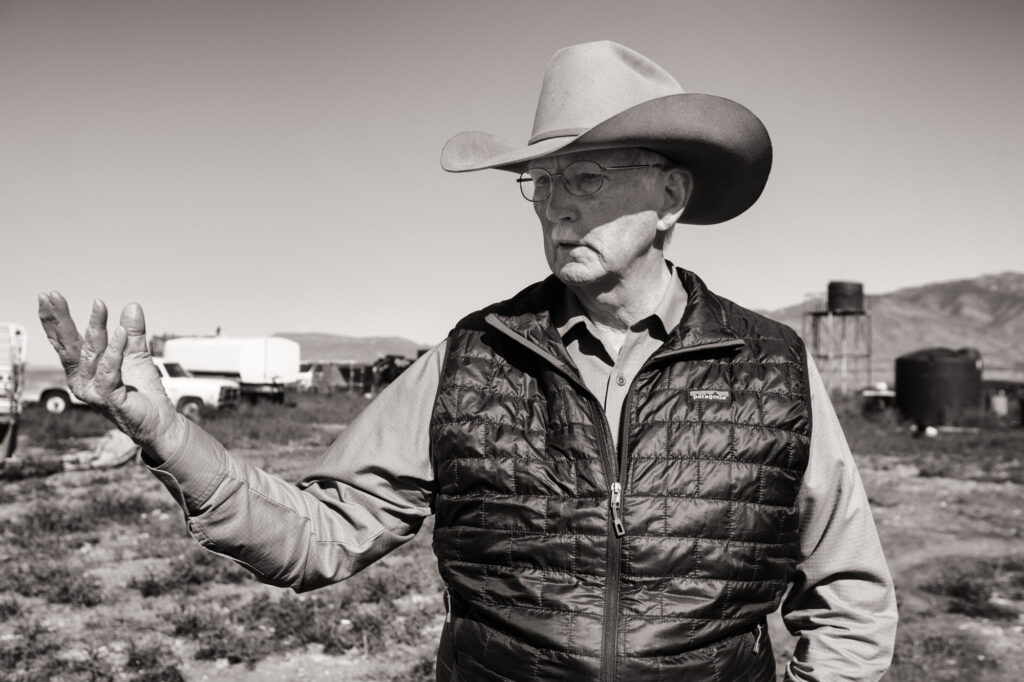

On a cloudless Tuesday afternoon this fall, Harvey E. Yates Jr., drives around Valencia County describing his plans for the future. At one corner, he envisions a thriving shopping center with a filling station and a hardware store. Elsewhere, he sees a ranch for wayward boys, and, finally, in the southeastern expanse — oil wells. His holdings are vast.

“Do you consider yourself a land baron,” I ask while looking out the window at acre after acre of sagebrush, desert clay and rolling foothills, much of them his. “Some call me an oil magnate,” he responds, as if the term has a sour taste to it. “People sure do like to put labels on you, don’t they?”

Yates, at age 80, doesn’t like to be boxed in. He is a lawyer, real estate developer, history lover, loyal Republican, cattle rancher and, yes, oil magnate. As of this year, he can add newspaperman to the list.

He is, after all, the grandson of a journalist-turned-wildcatter — Martin Yates Jr., the first person to discover a commercial oil field on state lands and the so-called father of the New Mexico oil business. It’s not surprising that he sees New Mexico through the prism of extraction, even at a time when the industry is facing an existential crisis.

To him, the looming crisis isn’t the methane clouds that hang over parts of New Mexico, the polluted aquifers from drilling, or even the prospect of earthquakes and climate change: The looming disaster is the possibility that government regulations will tighten and the industry will stop producing.

“If the oil and gas industry pulled out tomorrow, that’s where your disaster would be,” as Yates recently argued before the Valencia County Commission. The industry provides roughly 30 percent of New Mexico’s general fund revenue: The state couldn’t function without it.

What Yates doesn’t mention is that the industry equally needs New Mexico. His grandfather, Martin, helped pave the way for an enduring relationship between the state and its extractive industries, and his descendants, including Harvey, have carried on in that spirit of exploration. By the early aughts, members of the Yates family reportedly owned more oil and gas leases on public lands than anyone else in the country. In 2015, Forbes Magazine ranked the family’s net worth at $2.5 billion, making it one of the 115 richest in the nation. A year later, Yates family members sold the privately held Yates Petroleum to EOG Resources for $2.5 billion (Harvey did not own an interest in Yates Petroleum and did not profit from its sale, he said). The company assets included 1.6 million total net acres, EOG reported.

Lucas Herndon, the energy policy director of the nonprofit ProgressNow New Mexico, puts it this way: The Yates family is “intrinsically wrapped up in the history of this state.”

Harvey Yates has devoted decades to keeping the mutual dependency alive. That includes striking out for new sources of fossil fuels, seeking political allies and finding platforms to win hearts and minds. Earlier this year, he helped buy a newspaper to “remedy,” in his words, “the fact that conservatives are so often canceled.”

In April, Yates led a nine-member investment group, El Rito Media LLC, to purchase the Rio Grande Sun, a family-owned newspaper based in Española — the heart of a Democratic stronghold. Just one month later, he appeared at the Valencia County Commission meeting to speak in support of a natural resources ordinance that he’d helped craft — one that would enable him to realize a decades-long ambition of drilling in the Albuquerque Basin, succeeding where no one else has. The measure, after drawing fierce community opposition, ultimately passed 3 to 2.

Through it all, his business, Jalapeño Corp., pumped more than $200,000 into the recent primary and midterm elections, 90 percent of which went to Republican candidates. His campaign contributions in this state were second only to Chevron’s.

His friends cast him heroically. “I have often referred to him as ‘Mr. New Mexico,’” wrote Tom Wright, a close associate and fellow newspaper investor, in an email. “When he sees something which needs improving, he is willing to spend his time and money to make the situation better.”

His foes have an altogether different opinion: “He’s 80 years old — he’s gotta be hardheaded and dogmatic,” said Don Phillips, a structural geologist who strongly opposes fracking in the Albuquerque Basin.

“And he has the money to do anything he wants.”

Valencia vagaries

Jalapeño Corp. is located in a nondescript building off of Albuquerque’s Central Avenue, its dim interior filled with heavy wooden furniture and accouterments of the past — an old rotary bit from the driest hole Yates ever drilled, a Depression-era photograph of grandfather Martin, and walls lined with framed newspaper clippings marking key events in history.

The headlines span Harvey’s lifetime, from the 1942 Battle of Bataan and Ronald Reagan’s presidency to Nancy Pelosi’s rise to power and the killing of Osama Bin Laden. The last on the wall is a cover story about him in the Santa Fe New Mexican: “Oil man locked in battle for ‘soul’ of state GOP.”

If there is any indication of Yates’ fixity of purpose, it’s an easel that holds various maps of Valencia County. Little blue squares mark the location of mineral rights like Tetris blocks and lines crisscross the pages designating the breadth of his surface holdings, held under an array of company names. He’s helmed many over his lifetime, but his primary company today is Jalapeño, an oil and gas firm.

His dreams of drilling the county’s depths date back 50 years — all the way back to his return to New Mexico after graduating from Cornell Law School, where he studied natural resource law in the 1970s. The vast high desert looked to him like a perfect place to strike oil, but to drill there he’d need to acquire thousands of acres of mineral rights. In the late ’70s, shortly after forming his first company, Cibola Energy Corp., he found his way in.

An Arizona company called Horizon Corporation had for decades conned people across America into buying undeveloped and essentially worthless tracts in Valencia County, with more rattlesnakes and sagebrush than much else. After being sued for fraud, the company offloaded its remaining assets to another developer — helped by a loan from Yates.

In return for paying part of the downpayment for the properties, Yates says he walked away with thousands of acres of mineral rights, while setting his sights on amassing more. He now estimates his total holdings in the county to be about 20,000 acres of mineral rights — giving him access to resources underground — and 7,000 acres of surface rights.

There was a big catch: Valencia County’s zoning laws “made it prohibitive to exploit one’s minerals,” he explained on a recent day in his office. They only allowed drilling in a patchwork of “mineral resource districts,” areas that didn’t hold enough land for successful exploration.

Wildcat drilling — to explore untapped areas — is only worthwhile in his book if there are 10,000 adjacent acres. Unfortunately for him, none of the available districts offered that much acreage, Yates said. “Nobody in his right mind is going to go drill in an area where you can only drill one well,” he noted, pointing to an old map of the county’s fragmented mineral resource districts. It’s his Exhibit A.

So Yates threatened to sue. He argued that such overly restrictive zoning laws deprive people of the use of their property and constitute a “regulatory taking” in violation of the Fifth Amendment, a common legal argument in the oil and gas industry.

Leaving resources in the ground also runs counter to New Mexico’s nearly 100-year-old Oil and Gas Act: The law looks askance at squandering, according to Joseph Schremmer, an associate professor of oil and gas law at the University of New Mexico. “To place oil and gas resources out of reach is considered a form of waste.”

Valencia County saw the writing on the wall. In 2021, the county’s lawyer, Dave Pato, drafted the Natural Resources Overlay Zone ordinance, with Yates’ own suggested edits. (Pato and the Planning and Zoning Commission did not respond to Searchlight New Mexico’s request for comment.)

The resulting NROZ, as it’s known, makes it possible to drill and extract all sorts of materials — oil and gas, gravel, metals, sand and more — in residential and other areas without having to go through the onerous process of changing their zoning status.

To listen to Yates, the model has worked beautifully elsewhere. “How many wells are under Fort Worth, Texas?” (The answer: more than 1,900 gas wells alone, and residents are paying the price, local headlines say.)

In Valencia County, Yates and others can now potentially run cattle on the surface and draw oil from the depths of the same property. Or, as Yates says, “you could have minerals and industrial development on top, or houses or so forth.” Applicants must first go through an administrative and a public hearing process, satisfy a number of provisions and meet federal standards for noise emissions, air contamination and water quality, among other things. But once those bars are met, the NROZ allows all manner of uses.

‘Water is life’

To a casual observer, the effort to rewrite the resource ordinance in New Mexico’s second smallest county might appear to be belabored and insignificant. But the stakes are enormous. If at any time in the future Valencia County opens up to fracking — a drilling method that uses massive amounts of water — many residents fear it will contaminate and drain the already strained aquifer that serves the entire region. The word “fracking” is never mentioned in the NROZ. It doesn’t have to be, they say. It’s an unstated threat.

“Water is life,” said Janice Lucero, a local farmer in the Pueblo of Isleta who learned from elders to consider the needs of descendants. “Those extractive industries, they don’t necessarily think about seven generations into our future. When we start to allow these types of developers, we’re literally risking our lives.”

At 80, Harvey Yates still isn’t afraid to play the heavy. He can’t count the number of legal actions he’s been involved in over the years — several in Valencia County alone — but decades of going to battle have only hardened his views about what’s wrong with New Mexico. His primary targets: Laws that infringe on his private property rights, a media landscape dominated by the Gannett franchise and a belief, above all, that progressive Democrats are “well-educated elites” who ignore the Constitution and fail to understand the true needs of the people. He counts Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham among them.

“The populace needs to be warm. The populace needs to be able to drive their car. The populace needs to have air conditioning.”

The populace, in other words, needs fossil fuels.

Yates came of age during the oil shocks of the 1960s and ’70s, a major downturn that included a foreign oil embargo, a historic oil shortage and tanking oil and gas prices. Washington’s response, in his opinion, only deepened the crisis.

“The oil industry went to hell,” he says of the era, a time that forged his fierce belief in laissez-faire economics. It was a lesson that’s been passed down like a Yates family heirloom ever since: “Your primary risk is not geology so much as it is government.”

Bad education outcomes and addiction, to him, result from long-standing federal government overreach, which “leashed” entrepreneurial drive and created a “virus in New Mexico’s programming.”

Ink in the veins

Yates hammers home his theories in widely published op-eds that rail against “progressive initiatives,” such as regulations to address climate change. “Soon we will sacrifice hundreds of Navajo coal jobs to the god of Global Warming,” he wrote for a 2018 Searchlight survey of political opinions around the state. “The expansion of the oil and gas industry outside of the traditional oil basins has been stopped. …Progressive-driven hysteria has killed drilling in southern Sandoval County” and idled it in Otero County, he opined.

For years, he wrote one op-ed quarterly, alternately proselytizing for the oil and gas industry, espousing conservative views and targeting political adversaries. Yates has always needed a medium for his message.

The apotheosis came in April when he bought the Rio Grande Sun with eight other investors for an undisclosed amount — a “GOP media gambit,” as one headline dubbed it.

Besides Yates, a former national committeeman for the Republican Party of New Mexico and chair of the RPNM, other investors included Ryan Cangiolosi, former Republican state party chairman; cousin Peyton Yates, owner of Santo Petroleum; Jalapeño Corp., represented by Emmons, Yates’ son and the company vice president; and Francisco Romero, Jalapeño’s accountant.

Another investor is the company Los Mocositos — which translates to little snotty brats — located at the Santa Fe address of Richard Yates, a cousin and real estate developer. There’s also Tom Wright, the global outreach director of Christ Church Santa Fe and an avid op-ed writer about conservative issues; Bryan Ortiz, a former lobbyist; and state Rep. Joseph Sanchez, a conservative Democrat from Alcalde, near Española. (A tenth investor, the new publisher, Richard Connor, came on board months later.)

Yates was the unifying force and biggest investor. “Because I put in more money than anyone else, I’m involved more,” as he described it. A second newspaper buyout is in the offing in the 3rd Congressional district, largely located in northern New Mexico; he declined to name the publication until the deal is finalized.

When partisans of any stripe buy a newspaper, it raises fears of biased news coverage or lack of transparency. But Connor, the publisher, said he made things clear to the new owners. “You’re not gonna run the newspaper. I am. And you’re not gonna make decisions. I am,” he recalled telling them. “And I gotta say that there has been absolutely not one ounce of interference, not one.”

The paper, family-owned for nearly 66 years, is located in Española, the hub of New Mexico’s solidly blue rural north, a constellation of Hispano villages and Indigenous Pueblos. It’s one of the few rural Democrat-majority Congressional districts in the United States, according to Bloomberg. Most Democratic strongholds are in densely populated urban areas, making El Norte, as locals like to call it, an outlier.

Yates makes no bones about wanting to chip away at Democratic dominance in the area. In 2018, his political action committee, New Mexico Turn Around, ran an internet ad aimed at convincing northern New Mexicans that “ultra-progressives” in the Democratic Party were “wolves in sheep’s clothing” who wanted to strip poor people of their land and water. “Progressives are destroying our culture,” it proclaimed.

Democrats, Yates believes, have been in power for far too long, and news outlets don’t express the conservative point of view.

Editorials and op-eds at the Rio Grande Sun have crept farther to the right since the buyout, and transparency, a cornerstone of journalism, has not always been evident. One op-ed, titled “Life and forgiveness after Roe v. Wade,” asserted that “The Common Law accepts the Creator as being the giver of life and forbids the taking of human life.” The June 29 piece failed to disclose that Tom Wright, the author, is one of the investors who bought the paper.

“It’s no longer a newspaper,” said local political activist Antonio DeVargas. “It’s just becoming a Fox News type thing.”

Yates says he is adamant about keeping the character of the Sun as a community paper that expresses multiple points of view. The pages will remain a place to “read about the child who graduated, about the fellow who died, the neighbor who left his wife,” he said. Local newspapers enrich communities, the argument goes.

Those on the other side of Yates’ battles argue that he is only out to enrich his business and expand the state’s conservative base.

Over the years, Yates has funneled hundreds of thousands of dollars to candidates with the power to craft or kill laws concerning the oil and gas industry. A recent report from New Mexico Ethics Watch detailed the industry’s considerable influence on elections and legislation, with a section dedicated to the Yates family.

Harvey Yates “wants to win seats that will protect his bottom line,” says Herndon, of ProgressNow. “His money and influence and politics have kept New Mexico reliant on a source of revenue that at best has been spotty and at worst ruins the planet.”

The thrill of the drill

While driving along a desolate highway in Valencia County, Yates tells me that Cibola, the name of his first company, was inspired by the seven cities of gold from Spanish conquistadors’ myth. For someone who seeks riches that lie thousands of feet below the surface of the earth, it’s a fitting moniker.

“The thrill of the catch” impels him, he says — that, and the possibility of finding another oil-rich basin outside of the San Juan or Permian. “The thrill will be even greater,” he goes on, “if there are a thousand people saying ‘it’s not there. It’s not there. You’re a fool to do it.’”

But it might be foolishly dangerous, according to geologist Don Phillips. While working for Tenneco Oil in the 1980s, Phillips made a close study of the Albuquerque Basin, which lies in the middle of the Rio Grande Rift — the only continental rift of its kind in the Western Hemisphere. Research showed that the rift is very slowly pulling apart, each new movement sending fault lines from the surface and through an aquifer to the greatest depths of the basement rock.

“It’s completely fractured to beat the band,” Phillips said. Already, the rift is seismically active and its strata fragile, much like the layers of a croissant. “The reason that they’ve never fracked in it before is because nobody has been stupid enough or mean enough to try it.”

In the Albuquerque Basin, which stretches 125 miles from Cochiti to Socorro, groundwater sits close to the surface and the aquifer filters naturally through the delicate fault lines. If fracked, high-pressure fluid could easily rupture the strata, sending chemicals into the aquifer, Phillips said. Disposing of waste fluid, meanwhile, would induce earthquakes. This is not speculative, he added, but “a scientific certainty.”

Oil men typically want to proceed despite the dangers, protesting that they’re entitled because of property rights. That leaves surrounding communities to fight for the public good, said Alejandría Lyons, a Chicana organizer for New Mexico No False Solutions, a statewide coalition of climate justice groups. “Those are always the two forces going to battle when it comes to the environment.”

It’s a battle, in her eyes, between the “Old and New World” — between Valencia County’s acequia communities and the Pueblos of Isleta and Laguna, and private property owners like Yates, who define progress in different terms.

Risky gambles, rich payouts

Other companies have tried conventional vertical drilling to tap the recesses of the expansive Albuquerque Basin, which potentially holds oil reserves in the Mancos Shale, on Valencia County’s southeastern flank. The first attempts go back to the early 20th century and continued until a 1970s effort by Shell Oil Co., which provided enough geologic information to encourage further exploration by other companies into the 2000s. None succeeded.

But Yates has always wanted to throw the dice.

Months before the NROZ ordinance was put to a vote, he admitted to one commissioner, Joseph Bizzell (who received a $1,500 campaign donation from Jalapeño in 2020), that the chance of finding a productive well in the Albuquerque Basin was slim. “A drilling project in the basin underlying Valencia County carries a statistical chance of success of somewhere between 5% and 10%,” Yates wrote Bizzell in an email.

Then why do it if the rate of success is so low? Drilling a well on a 10,000-acre expanse is essentially a “scientific experiment” he explains: The more wells you drill, the higher the possibility of eventually hitting paydirt.

“If I show you a map of the Permian Basin, it looks like a pincushion — well after well after well,” he says, drawing a rough diagram for me in his office. And because of all that conventional drilling, operators found prodigious oil deposits in “non-conventional zones” — his term for areas that employ horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing. In short, fracking.

Yates will not use the word “frack” without qualifying it in exhaustive detail. Fracking, he believes, is a loaded and misused term, wielded by environmentalists to inflame the public. He prefers the industry’s term, “non-conventional drilling.”

Despite what others think, Yates says he does not run a fracking operation in the popular sense of the word. “As an operator, we have never drilled a horizontal well,” he says. He has chiefly been a wildcatter, discovering new lodes that others might eventually drill vertically, the old-fashioned way, or frack. He has, however, entered into operating agreements with enterprises that do fracking; this can include Jalapeño assuming part of the risks and profiting if the venture is successful.

According to a podcast featuring Emmons Yates, Jalapeño currently owns an interest in some 800 to 1,000 wells in the Southwest, which comprises about 95 percent of the company’s revenue stream.

When asked to venture a guess, Yates says he doesn’t think the Albuquerque Basin will be fracked in his lifetime.

Local opponents don’t buy it, and neither do activists across the state. They think fracking will happen sooner rather than later, and the damage it causes will linger long after he’s gone.

“You won’t live long enough to see it,” K.A. McCord, of the grassroots group Valencia County Water Watchers, told Yates after the resource ordinance was passed, “but we will.”

‘All roads lead back to Harvey’

On another Tuesday afternoon, I drive around with Amber Jeansonne and Ann McCartney, members of Valencia County Water Watchers, trying to identify where the drilling might take place. Yates has not yet applied for drilling permits, according to the state’s Oil Conservation Division, but the women worry they’ll land at any time.

We pull over along stretches of the road and consult a navigation app called OnX, which gives some of the most comprehensive data available on public and private lands. The shapes on McCartney’s phone translate to islands of Yates’ holdings.

Looking out into the distance, we find those massive swaths, framed on the east by the Manzano Mountains. In some places, he owns both sides of the highway.

“All roads lead back to Harvey,” Jeansonne says. “It’s unsettling.”

Clarification: An earlier version of this story stated that the Yates family sold Yates Petroleum for $2.5 billion, inaccurately suggesting that Harvey E. Yates Jr. profited. According to Yates, he did not own an interest in Yates Petroleum in 2016 and thus did not profit from its sale.