Does Indian Creek Island, known as Miami’s ‘billionaire bunker’, need a new nickname? Situated just off the north end of Miami Beach, the gated community has long been a favourite of America’s rich and famous, with financier Carl Icahn and former first daughter Ivanka Trump among its residents. But a new neighbour has taken things to the next level.

[From the magazine: Populism is on the march – again]

‘I love Miami,’ wrote Jeff Bezos (net worth $170 billion, so not just a billionaire but a ‘centibillionaire’) in an Instagram post, as he announced his intention to up sticks from Seattle – Amazon’s HQ since 1994 – and relocate to South Florida. Having stepped down as Amazon chief executive in July 2021, Bezos clearly has more time on his hands. And where better to spend some of it than at a $79 million mansion in Miami’s most exclusive enclave?

Closely guarded by elite security, Indian Creek isn’t accessible to outsiders (when I was in Miami late last year I caught a glimpse of it, or at least some of its palm trees, from a vantage point across the water in the well-heeled Surfside district). Yet elaborate details of its 41 mega-mansions have become the stuff of legend on celebrity news sites. Bezos’s new estate – which contains a 19,000 sq ft, seven-bedroom mansion – has been no exception on that front. Bezos is reported to have purchased two adjoining properties, with a home cinema, a wine cellar, a sauna and ‘stately grounds’.

Yet Indian Creek is hardly the only part of Miami to have courted UHNWs in recent years, many of whom have made the city their new home. Eye-catching recent arrivals include Citadel founder Ken Griffin, venture capitalist Peter Thiel and billionaire hedge-funders Scott Shleifer and Daniel Loeb. According to wealth research firm Henley & Partners, there are now 12 billionaires resident in Miami. On the next rung down, the city also contains the largest share of America’s centimillionaires.

[From the magazine: Family offices: is the private equity party over?]

This trend has come largely at the expense of other US cities. ‘We’re seeing a huge number of people moving from New York and California, as well as financial types from Chicago,’ says Jennifer Goldstein from Official, a high-end realtor that also serves the Hamptons and Los Angeles. Unlike much of the US, Miami’s real estate market has hardly cooled at all in the past 18 months. ‘We’re still seeing new records set for waterfront properties,’ Goldstein adds.

Content from our partners

If it’s good enough for Jeff Bezos…

To get a sense of what this great wealth surge looks like in practice, I head to Sunny Isles Beach. This island municipality was once a sleepy backwater, but its skyline is now dominated by branded skyscrapers carrying the names of Porsche, Armani and even Trump.

All three towers were brought into being, at least in part, by larger-than-life property developer Gil Dezer. He’s now looking to build a Bentley tower too. Sitting in his office in Sunny Isles Beach, he provides Spear’s with a bullish assessment of the city’s luxury residence market. ‘When Carl Icahn moved his offices down here, you saw 15 different sales of properties priced over $10 million,’ says Dezer. ‘It’s not just the billionaires moving down here, it’s all their executives too, and those guys make bank.’

What does $10 million get you in Miami? A three-bed unit in Dezer’s Porsche Design Tower – home of ‘The Dezervator’, a car-sized elevator that transports owners and their vehicles to personal garages on the same floor as their residence – will set you back around $7 million. As a rule of thumb, prices in Miami’s most fashionable districts (notably the waterfront areas around Coconut Grove) frequently stretch above $700 per square foot.

[See also: Driven by design: how car galleries have become the new motoring status symbol]

Like many people who work with Miami’s super-rich, Dezer isn’t shy when it comes to sizing up someone’s wealth. ‘If someone is buying an $8 million second home, you can be sure they’re not spending the last of their cash,’ he says. ‘Most of my buyers are worth at least $100 million.’ Many have boltholes in other top-tier cities, including London and New York.

Bezos has voiced several reasons for his move to Miami. America’s second-richest man has spoken of his desire to be closer to his parents and – less prosaically – to spend more time on his Blue Origin space exploration project, which is based in Cape Canaveral, three hours’ drive north of Miami. It perhaps helps that both Bezos (the son of a Cuban migrant) and his partner Lauren Sánchez (born to a second-generation Mexican-American family) are both fluent in Spanish, which gives English a run for its money as Miami’s most spoken language. But are there other factors drawing the world’s rich to the city?

Sun, safety – and seriously low taxes

Florida’s Republican governor, presidential hopeful Ron DeSantis, has made much of the state’s low-tax credentials. Indeed, not only does the Sunshine State’s constitution forbid the collection of taxes on income, but its comparative position to other states has grown even stronger in recent years – thanks to the efforts of one of its more divisive billionaire residents.

Since the advent of federal income tax in 1913, US residents have been able to deduct the value of local taxes against their bill. But in 2017 the newly minted Trump administration sought to cap the amount deducted at $10,000. As a result, tax practitioners at EY estimate that someone moving to Florida from California or New York could slash their federal tax bill by around 10 per cent overnight.

[From the magazine: Introducing Spear’s Magazine: Issue 90]

Yet those who advise Florida’s HNW classes have a slightly different perspective. ‘I actually think the low-tax argument is overstated,’ says Michael Kosnitzky, a private client lawyer – and long-time Miami resident – with the full-service law firm Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman. ‘In my experience, lifestyle factors are a bigger deal. I have a billionaire client who just moved from New York. He was telling me that when he goes to the drugstore there, everything is locked away because of theft. Needless to say, that doesn’t happen in Miami.’ On a similar theme, he adds, UHNWs feel much safer in Miami. ‘They can go for dinner on South Beach and not need their bodyguards with them all the time.’

Like other private-client lawyers in South Florida, Kosnitzky says business is booming. Some of that comes from new clients, but existing Pillsbury clients who have moved from New York are looking for help too. ‘When they move here, they need to update their estate plans and restructure their family office,’ he says. Some need to re-register their personal aircraft.

[See also: What is succession planning? How to pass on wealth, control and knowledge to the next generation]

In Brickell, Miami’s financial district, where Pillsbury has its office, the pristine streets pulse with activity. Beneath imposing offices housing corporate lawyers and money managers, advisers in smart, sober suits (a far cry from the stereotypical Miami uniform of pastel hues and lurid prints) weave from high-rise offices to five-star hotels (including the Four Seasons and, just over the water, the Mandarin Oriental), luxury restaurants (including an outpost of Richard Caring’s Sexy Fish), and even the occasional traditional cigar shop such as Village Humidor (in South Florida, some habits die hard). The pandemic and the economic crunch feel as distant as the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Playground rules

But beyond the glass high-rises of ‘Wall Street South’, the influx of wealth is making its presence felt in other ways. Demand for places at Miami’s best private schools – the likes of Miami Country Day School (the school of choice for newly divorced Miami locals Tom Brady and Gisele Bündchen for their kids) – hugely outstrips supply. Not only does Miami have a much smaller selection of schools than New York or Chicago, but also prohibitive land values are making it difficult to add more to the mix.

‘Even families who you would have considered to be a shoo-in are now looking for outside help to strengthen their applications,’ says Miami-based college admissions consultant Christopher Rim, founder of Command Education. He tells Spear’s he moved to Miami in 2021, in response to a spike in requests in the city from nervous parents looking for coaching and intel on the all-important selection process.

[See also: What are the most expensive private schools in America?]

For new Miami residents, the preference among schools toward legacy applications, including those with siblings already in the system, presents another potential barrier. Among locals, there are whispers that some well-heeled families may have decided to take a more direct approach, with tax filings from several of Miami’s most sought-after schools showing a sharp rise in donations. Revenues to Ransom Everglades, a tax-exempt private school, have risen almost 50 per cent since the pandemic.

New arrivals face other obstacles too, not least satisfying the all-powerful Inland Revenue that Florida should be considered their primary residence. One local tells Spear’s about an enterprising trick among charitable hospitals: courting donations from newcomers seeking to join a philanthropic board to strengthen their residency claim.

Getting Messi in Miami

Predictably, the great millionaire migration has turbocharged Miami’s cultural and culinary scenes too. ‘We have restaurants like Bouchon [a signature project from Californian restaurateur Thomas Keller] which wouldn’t have opened here a few years ago,’ says Jennifer Goldstein. Miami now ranks sixth in the US for Michelin stars.

The city’s cultural scene is thriving, too. Visitors to Art Basel Miami Beach, the global art fair popular with HNW buyers, rose from 30,000 in 2009 to more than 80,000 in 2022. ‘Since it launched in 2002, Art Basel in Miami Beach has driven Miami’s ascent to the status of art world capital,’ says Arun Kakar, art market editor at Artsy. ‘The art fair is not only the largest in the US, it’s now an established fixture in the international art world calendar, with few equals in terms of international clout, artwork value and HNW clientele.’

[See also: Outstanding art advisers for UHNWs]

Then there’s the Miami Open tennis tournament and, as of last year, a Formula 1 Grand Prix. And finally the city’s latest megastar: World Cup-winning footballer Lionel Messi, now at Inter Miami after a $150 million deal brokered in part by David Beckham.

What does it all mean for those who have long called the city home? A familiar local grumble is that Miami’s starry turn has been terrible for traffic, making the city America’s fifth most congested. Likewise, Miami’s slightly ageing airport has become notorious for delays – a serious impediment for a city selling itself as a business hub. It also lacks a fast-track lane for business travellers (although that won’t be a concern for the UHNW visitors making use of the city’s three private airfields).

[See also: Is Formula 1 becoming the hangout of choice for UHNWs?]

Bubble trouble

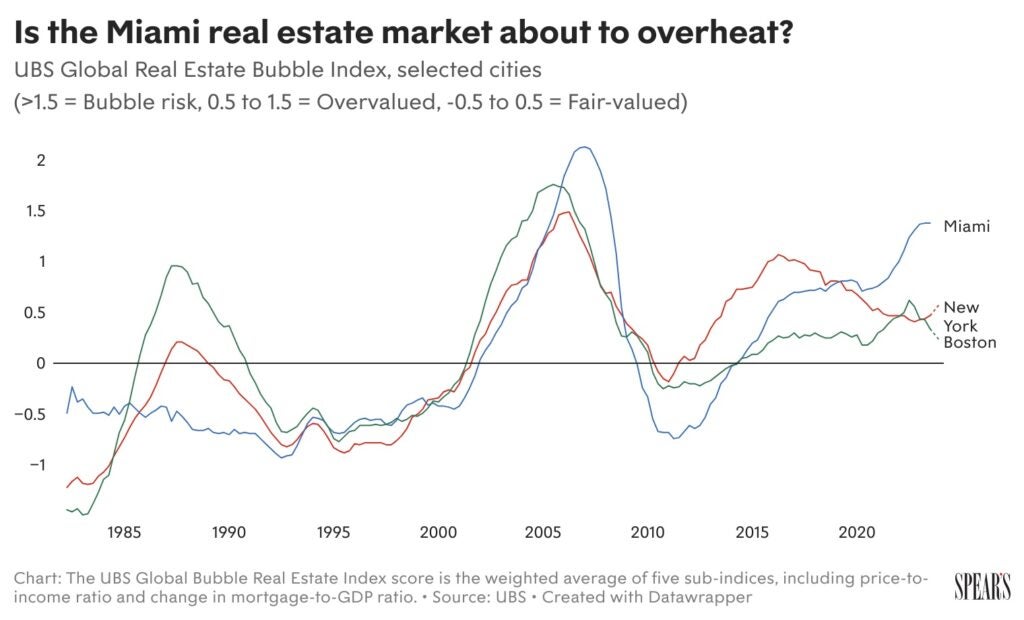

Miami has boomed before, most notoriously before the global financial crisis. Given the latest headwinds facing the economy, could the city be vulnerable to another downturn? Ominously, the city recently ranked third in the world (and first in the US) in UBS’s Real Estate Bubble Index. Maintaining current real estate prices, says the bank, would equate to defying economic gravity.

But while rocketing prices can suggest a bubble, it is by no means certain. Miami’s luxury market has benefited from HNW buyers seeking to move their cash away from less certain jurisdictions, in particular from Central and South America. Headlines from Argentina – whose eccentric new president has pledged to scrap the central bank – suggest that window is far from closed.

A more pressing vulnerability comes from the city’s exposure to climate change: not just in terms of rising sea levels, but also the intense rainstorms that frequently hit South Florida. By some estimates, Miami now has the costliest building insurance policies in America. In 2021 the metropolitan area of Miami-Dade (the county encompassing much of urban Miami) became the first place in the world to appoint a chief heat officer – a recognition of the immediacy of the threat. Daytime temperatures for much of the year are in the mid 30s.

What happened to the crypto-bros?

Until now, the question of resilience has been confined to more prosaic matters. In the years before the pandemic, for example, Miami set out to become the world’s crypto capital. Its energetic mayor, a self-confessed Bitcoin enthusiast called Francis Suarez, even backed the city’s own digital currency, MiamiCoin, as part of a strategy to lure tech investors to the city.

In March 2021 – following another Bitcoin bull run – Miami entered into a deal with the now-disgraced crypto mogul Sam Bankman-Fried to rename one of its stadiums, home of the Miami Heat basketball team, after his crypto exchange. The FTX Arena name lasted less than 18 months (in April 2023 it became the Kaseya Center, after a partnership with a local software firm).

[See also: The 2023 Spear’s Wealth Management Indices]

These days, the fast-spending crypto-bros are nowhere to be seen, their absence acutely felt by the city’s nightclubs. Indeed the closest Spear’s comes to experiencing crypto-wealth in Miami is spotting an unplugged Bitcoin ATM gathering dust in a convenience store. But those who have worked with the city’s tech entrepreneurs aren’t worrying too much just yet.

‘Miami has always moved in waves,’ says Michael Kosnitzky. ‘Right now the excitement is all about tech. Before that it was wealth managers opening Latin America offices. Prior to that it was real estate.’ Each time, he adds, a new tranche of lawyers and other advisers will move to Miami. Inevitably, not all of them last the course.

Developer Gil Dezer is equally unfazed. ‘I don’t think a single one of those Bitcoin guys bought an apartment from me, despite them registering interest,’ he says with a dismissive wave. ‘Sure, those guys got rich overnight, but that was all they had. If they sell their Bitcoin, they have no way of making more.’

By contrast, the current wave of incoming billionaires are unafraid to splash the cash. After relocating the Citadel headquarters to Miami in early summer 2022, Ken Griffin is already expanding his fund’s footprint in Miami. Last year he took on six floors in a newly opened prestige high-rise in the heart of Brickell. He is also reportedly investing personally in a major construction project in Palm Beach – one of Miami’s plushest zip codes.

In an interview with Bloomberg in November, Griffin went on to praise Miami as ‘the future of America’, predicting the city could be on course to eclipse New York. Maybe in 50 years, he suggested, instead of calling Miami’s financial district ‘Wall Street South’, people will refer to the cluster of gleaming skyscrapers in Lower Manhattan as ‘Brickell Bay North’. For Miami’s new super-rich residents, anything seems possible.