SHREVEPORT, La. (KTAL/KMSS) – His name was Odessa St. Strickland, and in the early 1900s he invented a device that traced and defined the boundaries of oil and gas deposits. In 1940 alone, 139/140 of the locations discovered by Strictland’s invention produced oil and gas. But Strickland’s big claim to fame came about because of his involvement in what many newspapers of the 1930s referred to as the first black-owned oil company in the United States.

Universal Oil, Gas and Mining Company’s headquarters was located at 1051 ½ Texas Avenue in Shreveport. UOGMC got its start at the very beginning of the Great Depression, when the company had only $20 left in its entire treasury after paperwork was filed for the charter.

Universal Oil, Gas and Mining Co. is not to be confused with Universal Oil Co., which attracted major media attention in the early 1930s when several New York City politicians were taken to court concerning their involvement with the company.

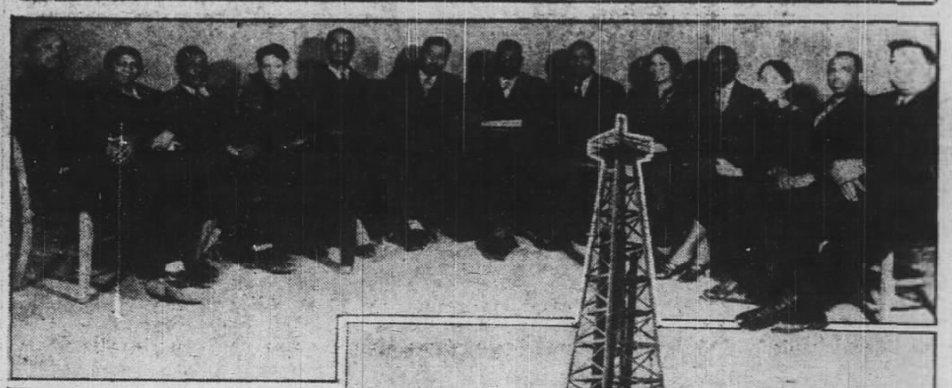

The charter was filed with the Caddo Parish Clerk in Oct. 1930. 5000 shares of stock of $10 par value were listed when the company was chartered. Officers were W. M. Rogers, president; R. L. Johnson, vice president; O. S. Strickland, secretary and general manager; and Dr. R. T. Nelson, treasurer.

General Manager O. S. Strickland grew the corporation until it owned and controlled oil lands, wells, drilling machinery, and carrying lines that were worth more than half a million dollars.

In Apr. 1931, the company completed its No. 1 J. T. Brown for a daily estimated production of 8000 barrels, according to the Longview News-Journal. The well was in the Pru Survey.

The company drilled a crooked well in 1931 and had to plug the hole at the 2400-foot mark to begin drilling again and straighten the hole, but the company also announced in that time period that they were beginning to drill a second hole in the same area immediately.

By the next August, the company amended its charter to increase capitalization to 10000 shares of $10 par value.

In 1932, three black women were on the board of directors. Fast forward to 1937 and four of the nine directors were women.

J. L. Jones was the president by 1937. Jones had been a beloved educator and principal in Minden. He had been President of the Louisiana Colored Teachers Association.

J. L. Jones Elementary School in Minden, Louisiana (Webster Parish) is named after him.

In Jan. 1934 the company was lauded in The Shreveport Journal for hiring only white labor.

“The Universal Oil, Gas & Mining Col, backed by several Shreveport negroes, are owners of the well, their first in the Converse area. Chief operations of the company has been in East Texas field where it has drilled three producing wells, according to C. L. Mills, white drilling and production superintendent. Only white labor and drillers are said to be used.”

But by the fall of 1936, a few of the high officials in the company were secretly entering into a conspiracy to sell out the only black-owned oil company in the United States. The company’s stockholders took action swiftly and dismissed the high-ranking officers in the company and fill the vacancies left with “officers who feel that Negroes should own the wealth of mother earth as well as any other nation.”

The company was known to shape and train young Black men and turn them into oil engineers, oil mechanics, and oil drillers. But in 1937, oilfield workers had to hold their ground when they were shot at by a white mob near Luling, Texas.

Universal had hit black gold on a major well northwest of Yoakum, Texas in August. The previous month Universal had a major problem when the cement on the No. 1 Schuebel well did not hold. The well began drilling deeper and proved that sometimes it pays to stop, think, and work harder when a problem arises.

By the end of 1936 Universal’s president, J. L. Jones, sold and delivered $27,000 worth of oil from wells in east Texas. Their sixth year of business closed successfully.

In 1937, the company made plans to build a $50,000 petroleum engineering department and attach it to the headquarters office. It was also predicted that the company would produce half a million barrels of pipeline oil.

Some white oilfield workers in the Shreveport area were insistent that people of dark skin should not share in the wealth created by the Caldwell County, Texas oil pool. They also said that Black engineers and oil drillers should not work in the same field as white operators.

But a Black unit of oil engineers, workmen, and drillers drilled 2,544 below the surface of the earth and tapped into one of the richest veins of oil in Texas history.

In 1938, Universal was called “the Greatest Negro Oil Organization America has Produced,” and the company fully believed it was more advantageous for black landowners to use Universal’s services than to use white-owned oil companies. One newspaper stated that “hundreds of Negroes have, during the past twenty-five years touched the magic wand, steeped in a pool of black liquid gold and in several instances some of them have been rated as millionaires. But “it should be kept in mind whatever its colossal amount, it represented only one-eighth of the cache which wise providence had hidden in the recesses of earth as a bounty for the black man who owned the land.”

The paper would further explain that the Universal Oil, Gas and Mining Company, “headed by a far-visioned, capable son of Oklahoma, O. S. Strickland has entered the oil drilling arena of this state for the purpose of claiming for Negroes their other seven-eighths of their oil rights. Mr. Strickland has conquered the intricacies of the oil game and today has an all-Negro drilling crew that knows how to pierce the earth to deep levels, where the rich oil deposits are. Mr. Strickland’s company is not an experiment. He is today paying dividends from producing wells in Texas and Louisiana fields. These wells were drilled by the same all-Negro crew soon to start operations at Langston, Oklahoma.”

The publication furthered that it takes faith to believe in the evidence of things not seen a mile and one half down in the earth: “…and that is why Negroes have been overlooking the other seven-eighths of the oil rightfully belonging to them. O. S. Strickland has that type of vision. He dreamed (and) became the master of his dream, and today he returns to Langston, the scene of his early childhood, to tell the Negroes he has found the other seven-eights of their wealth. He may dig a dry hole at Langston, but he will dig it with an all-Negro drilling crew who has proven their ability to actually produce paying oil wells in Texas and Louisiana.”

The company was granted a drilling permit by the State Conservation Department, Oil and Gas Division, to drill an oil well to a depth of 5200 feet. The first well was set to be drilled in a corner of property belonging to Langston University.

At the time, Universal had 13 producing oil wells.

Unfortunately, the well at Langston University was not successful. But the perception of the company’s abilities by that time period was impressive. The Black Dispatch reported on such in Mar. 1938:

“Think of the great riches that would today be in the hands of black people of Oklahoma had they had the faith to organize oil drilling companies as has Mr. Strickland and then train black men to pierce the earth to its mineral stratums. Our faith has not extended past an oil lease. Observe the wonderful opportunity that has come to a black man who in a certain sense has had the ‘faith of a grain of mustard seed.’”

Universal moved their drilling operations to the Illinois Oil Basin and began drilling on the H. O. Williams lease in the Centralia Oil field by Aug. 1938. They were after what others were already getting: between three to seven hundred barrels per day from each well drilled. And they were, by that time, known as the only colored company operating the new field. More than that, they were becoming nationally recognized as the only all-colored oil company in America.

A Chicago newspaper even featured J. L. Jones, an “oil magnate” from Shreveport, La., in a list of highly successful African Americans who could serve as role models for children.

In 1939, O. S. Strickland was credited with inventing the electronometer, which defined the boundaries of oil and gas fields. Strickland said he expected his invention to ” benefit colored landowners across the nation.”

The invention gave Universal an incredible advantage in the oilfield.

By 1941, Universal had acquired a cable tool drilling rig that they installed on a well in Kentucky. The rig was destroyed completely in Aug. 1940. The culprit? A gas blowout. But in the same year, daily oil production from all Universal wells in Texas, Kentucky, and Louisiana hit 380 bbls/day.

Strickland returned to work in Texas and in 1942, he went into business with white men.

Before his death, Strickland wrote an editorial for black citizens of Shreveport.

“It has been our ambition to organize a company that could take in all phases of the oil and mining industry with an exclusive Negro personnel, and employ men and women to operative every phase of the business, in which we have been considerably successful, for we have Negro drillers, lease operators, field agents, and geologists and engineers, all of whom are Negros and trained in their particular line of work.”

Strickland was writing on the subject of WWII and the oil industry.

“We pledge to do our bit for the safety and protection of our country,” he promised.

He died on Sept. 16 of the same year and was buried in the Sheppard Street Cemetery in Minden, Louisiana.

On his tombstone, a hand-carved image appears to be a flowing oil well.

Research suggests that, despite the claim by multiple publications in the 1930s that Universal was the first black-owned and operated oil company in the United States, a few other oil companies have also claimed similar titles. For example, in 1902 the Wilgera Oil Company was hailed as the first colored oil and gas company to be incorporated in the United States.

SOURCES:

- “Negro co. Completes new Texas oil well,” The Pittsburgh Courier, Aug. 14, 1937, pp. 12

- “The other seven-eighths,” Mar. 12, 1938, The Black Dispatch, pp. 4

- “Negro oil co. Jubilant over big G U S H E R,” The Northwest Enterprise, Apr. 30, 1931, pp. 1

- “Converse townsite gets 4th producer,” The Shreveport Journal, Jan. 15, 1934, pp. 13

- “Edwards test verdict near,” Forst Worth Star-Telegram, Aug. 30, 1936, pp. 24

- “DeWitt Well to Recement,” July 8, 1936, Fort Worth Star-Telegram, pp. 2

- “News Flashes,” The Arizona Gleam, Jan. 15, 1937, pp. 3

- “Universal Oil Co. to sink well on Lanston U. land,” The Black Dispatch, May 7, 1938, pp. 7

- “Universal Oil, Gas & Mining Company brings fortune and golden opportunity to Oklahoma!,” The Black Dispatch, Mar. 12, 1938, pp. 3

- “Negroes share Centralia rich new oil field,” The St. Louis Argus, July 29, 1938

- “Logan County,” Shawnee News-Star, Aug. 13, 1938, pp. 6

- “National Guide Right Week for Negro Youth,” Chicago Sunday Bee, May 1, 1938, pp. 6

- “Invention and Inventor,” The Pittsburgh Courier, Sept. 23, 1939, pp. 22

- “Black American Oil Industry History,” by Mary Barrett, Centenary College of Louisiana, Nov. 2023

- The (Shreveport) Times, Oct. 12, 1930, pp. 1

Gary D. Joiner received a B.A. in history and geography from Louisiana Tech University, an M.A. in history from Louisiana Tech University, and a Ph.D. in history from St. Martin’s College, Lancaster University in the United Kingdom. He is a Professor of History at Louisiana State University in Shreveport, where he holds the Mary Anne and Leonard Selber Professorship. He is the director of the Strategy Alternatives Consortium and the Red River Regional Studies Center. His research interests span military history, local and regional studies, and defense-related projects. He is the author or editor of 38 books, including: 9/11: A Remembrance, Henry Chilvers: Admired by All (2018), History Matters, Shiloh and the Western Campaign of 1862, One Damn Blunder From Beginning to End, Through the Howling Wilderness, No Pardons to Ask Nor Apologies to Make, Little to Eat and Thin Mud to Drink, Mr. Lincoln’s Brown Water Navy, Red River Steamboats, Historic Shreveport-Bossier, Lost Shreveport: Vanishing Scenes From the Red River Valley, Historic Haunts of Shreveport and Wicked Shreveport, Wicked Shreveport, Historic Oakland Cemetery, Local Legends of Shreveport, Shre3veport’s Historic Greenwood Cemetery: Stories in Granite and Marble, Red River Campaign: The Union’s Last Attempt to Invade Texas, and The Battle of New Orleans: A Bicentennial Tribute. Dr. Joiner is also the author of numerous articles and technical reports and served as a consultant for ABC, CBS, Fox News, PBS, the Associated Press, A&E Network, C-SPAN, the Discovery Network, HGTV, the History Channel, MSNBC, SyFy, and MTV among others.

Among his awards and honors are: the Aaron and Peggy Selber Writing Competition Prize; Albert Castel Award; A.M. Pate, Jr. Award, Listed in the International Biographical Centre (Cambridge, England) Outstanding Academics of the 21st Century; Jefferson Davis Award nomination; Silver Spur Award nomination, Western Writers of America; Army Historical Foundation finalist, Distinguished Writing Award; Douglas Southall Freeman Award nomination, MOS & B; Book of the Month Club featured alternate, History Book Club Main Selection, and Military Book featured alternate; Lifetime Achievement Award and Life Membership, Red River Civil War Roundtable, Alexandria, Louisiana; Charles L. “Pie” Dufour Award, for Preservation and Scholarly Contributions in the field of History, New Orleans Civil War Roundtable; A.M. Pate Distinguished Service Award for Civil War History by the Fort Worth Civil War Round Table; Louisiana Trust for Historic Preservation, Preservationist of the Year Award for 2010.

Jaclyn Tripp is an investigative reporter with KTAL NBC 6 News in Shreveport, where she focuses on the history, culture, and environment of northwest Louisiana. She is a United States Air Force Veteran, a graduate of Southern Arkansas University and DINFOS, and won the Louisiana Press Association’s award for Best Investigative Reporting. While on active duty, Jaclyn served as a military artist and photographer and as the assistant to the Little Rock Air Force Base‘s historian. She was born in Shreveport and is a native of Webster Parish.