The world's rich countries are not reproducing themselves. A total fertility rate (TFR) of 2.1 (the number of children an average woman has over her lifetime) is considered replacement fertility. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the TFR in the United States in 2022 was approximately 1.67. According to the 2023 World Fact Book, Sweden's TFR was 1.67, Germany's 1.58, and Japan's 1.39. This means that without immigration, the world's rich countries would quickly shrink in size. Declining birth rates, declining birth rates, declining birth rates, and a disproportionate increase in older people in the rich world make headlines because they have many negative social consequences. These include issues with government funding for pensions and health care, and increased feelings of loneliness as more people live alone.

However, trends at the aggregate level across countries mask trends emerging among individuals in these countries. In my new book, co-authored with Martin Feeder and Suzanne Huber, Not so strange after all: the changing relationship between status and fertility, for much of the 20th century, poor people had more children than rich people in countries such as the United States, but the new trend is that wealthier men and women are more likely to have children. We note that a trend is emerging. Men and women who are not very well off.

Readers of this blog will not be surprised by this change. Given that marriage is more concentrated among economically wealthy people in the United States and other countries, and in most countries (even Scandinavia) marriage remains the preferred arrangement for raising children. , . In an era when fewer and fewer of the population are getting married and having children, a stable family life is increasingly becoming the preserve of the wealthy elite.

In our book, we present studies from a variety of countries in East Asia, Europe, the United States, and the United Kingdom that document the changing relationship between status and fertility. For example, in Japan, men with higher incomes are more likely to get married and have children. Naohiro Ogawa et al. found that in Tokyo in 2003, 85% of men aged 25 to 34 in the lowest income category were unmarried, compared to only a small percentage of men in the highest income category. It was found that 35%. In East Asia, childbearing is so closely tied to marriage that these high-income men who marry are also more likely to have children. For example, recent research shows that pro swan found a positive relationship between annual income and number of children for Japanese men in all birth cohorts from 1943 to 1975, with high-income men having, on average, more children than low-income men. It was discovered that it was producing . Similar trends are evident in Taiwan, South Korea, and China.

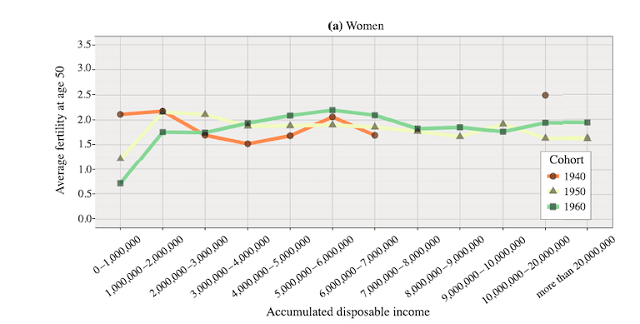

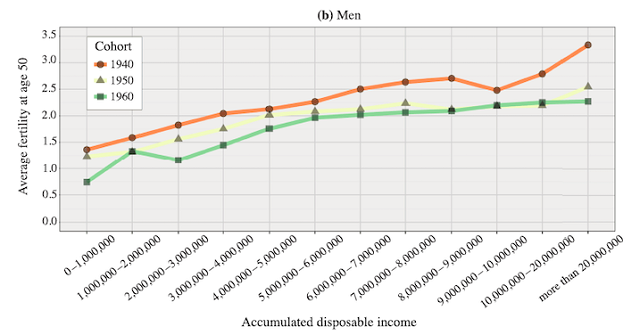

In Sweden, among recent cohorts, high-income and highly educated men and women are the most likely to have children, while low-income and low-educated men and women are the most likely to have children. (see Figures 1 and 2). Even though cohabitation rates are very high in Sweden, people who are wealthy and have children are also more likely to (eventually) get married.

Figure 1. Average fertility rate for women at age 50 by cumulative disposable income,

For Swedish cohorts born in 1940, 1950, and 1960. (source cork 2022)

Figure 2. Average male fertility rate at age 50 by cumulative disposable income,

For Swedish cohorts born in 1940, 1950, and 1960. (source cork 2022)

In the United States and United Kingdom, there is also a positive relationship between personal income (excluding education) and the number of children a man has, with men with higher incomes having more children on average. In the US and UK, despite high non-marital birth rates, most children are born to married parents, and high-income men have higher birth rates because these men are more likely to marry . For example, a study published in 2022 found that evolution and human behavior, Martin Feeder and Suzanne Huber found a positive association between men's income and marital status in US data from the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study. They found that personal income predicted about one-fifth of the variation in marital status. In the United States, income is becoming more important when men get married. In another study of U.S. Census data, Feeder and Huber found that the difference in marital status explained by income for men ages 46 to 55 increased from 2.5% for men born in 1890 to 1910 to 2.5% for men born in 1973. It was found that the increase was approximately 20%.

Figure 3. Predicted total number of biological children by month

Personal income from all sources for men and women in the United States (Source: Hoploft 2023)

For women in the United States, a U-shaped relationship between education and fertility is emerging. However, as in many countries, there remains a negative relationship between women's personal income and fertility, with higher-income women likely to have fewer children than lower-income women.

Figure 4. Fertility by women's education, 1980 and 2010 (Source: Federal Reserve Bank)

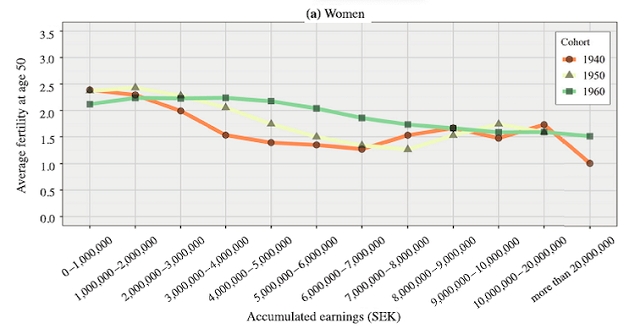

Much of the negative relationship between personal income and fertility for U.S. women appears to reflect the trade-off women face between earning an income and bearing and raising children. This is supported by Swedish data. In Sweden, these trade-offs are ameliorated by generous state benefits for parents. Both parents will each receive approximately eight months of paid parental leave while being paid 80% of their salary. Including such benefits in total income implies a positive relationship between income and fertility for both men and women, but excluding all benefits and remittances from the country. When we examine income from work, we find that women with higher incomes still have fewer children than women with lower incomes. woman.

Figure 5. Average fertility rate for women at age 50 by cumulative income,

For Swedish cohorts born in 1940, 1950, and 1960. (source cork 2022)

This negative relationship between women's income from work and number of children is because women without children are more likely to work outside the home during their lifetime. For example, using data from the 1979 National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, Lenske Verwey and her coauthors found that women who worked outside the home throughout their lives were less likely to work outside the home than women who worked outside the home less frequently. They found that they were about three times more likely to have no children. .

Recent changes suggest that rewards for children and families are increasingly limited to the wealthy, and this trend is likely to continue. This is not good for individuals, and it is not good for society as a whole. However, the government's existing policies do little to solve the problem. In fact, the governments that provide the most support to families with two working parents, such as the Nordic countries, are actually at the forefront of this trend.

Although our book does not derive policy implications from changes in the relationship between status and fertility, it is easy to do so.Unlike bloomberg Author Justin Fox suggests the solution is to emulate work-family policies in countries like Sweden, but this will only exacerbate the trend of rich people having more children. I believe.

A better approach is to accept that there are differences between men and women with respect to gender and social behaviors such as parenting (as predicted by theories of evolutionary biology). Work and family policies in countries such as the Nordic countries largely ignore these differences and aim to promote full-time employment for women. This is, in part, a reaction to a history of patriarchal rules that limit women's rights and opportunities. However, there is a difference between removing barriers to women's labor force participation and encouraging equal employment outcomes for men and women. There is no legitimacy to laws or policies that limit women's opportunities, but they do not require that all workplaces have equal proportions of men and women or encourage men and women to behave in exactly the same way. or encouraging them will likely have negative consequences. These policies are likely to hinder family formation and childbearing, especially given the gender differences in child-rearing. For example, to the extent that such laws and policies mean replacing men with higher-paying jobs, one effect could be that more men end up in jobs that do not allow them to support their families. Even in the Nordic countries, these low-wage men are less attractive fathers, despite the many benefits afforded to working parents. This means that poorer couples have fewer births.

On the other hand, there are policies and practices that support families, such as providing better public schools, crime prevention, and safer communities, as well as policies that limit the cost of health care and higher education and promote productivity. . All of the family housing can reduce the cost of family formation. A family-oriented culture also helps. The wealthy may always be able to afford to have more children, but social engineering that seeks to eradicate gender differences in work behavior and policies that increase education, health care, and housing costs for families are likely to reduce this tendency. It will only make things worse.

Rosemary L. Hopcroft is Professor Emeritus of Sociology at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte.she is the author of Evolution and gender: why it matters for modern life (Routledge 2016), editor The Oxford Handbook of Evolution, Biology and Society. (Oxford, 2018), and author (co-authored with Martin Feeder and Suzanne Huber) Not so strange after all: the changing relationship between status and fertility (Routledge, 2024).