Hundreds of products, including coffee, tofu and cars, need to be shipped to other parts of the country because the ports are closed to most shipping traffic. Three temporary waterways restrict access to the Port of Baltimore.

To illustrate how the supply chain has been disrupted, The Washington Post examined the delivery process for some products imported from overseas to serve Compass customers.

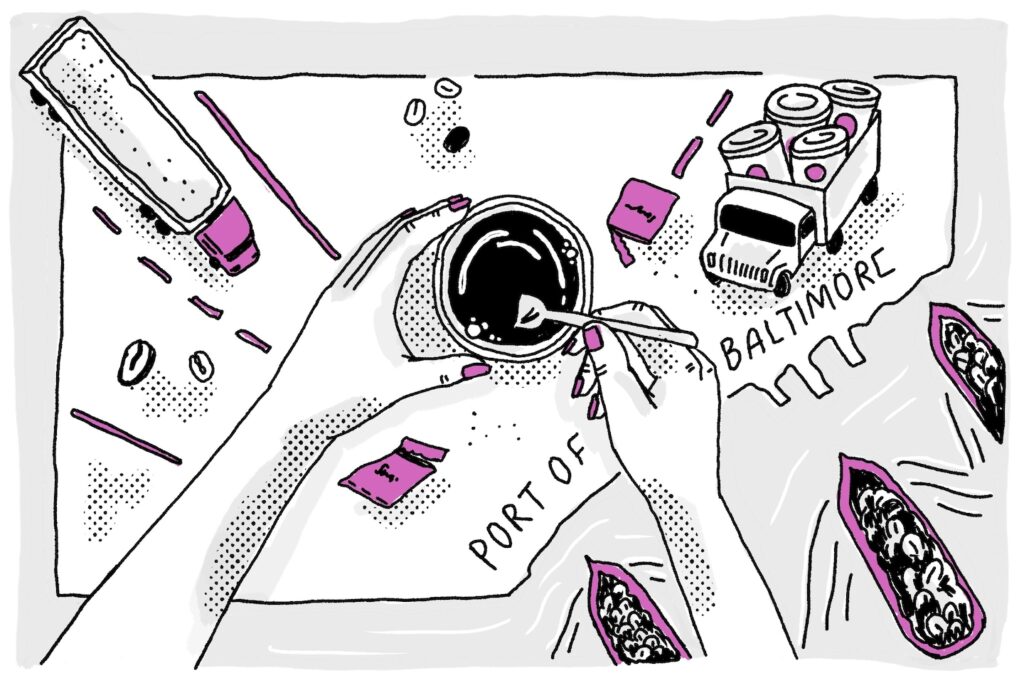

From all over the world to your hands

Compass sources coffee beans from Kenya, Ethiopia, Indonesia, Brazil, Guatemala and Colombia. These beans are loaded into shipping containers (42,000 pounds each) and sent to sea.

They arrive at the Port of Baltimore, which receives more than 8 percent of the nation's coffee beans. The only ports that were importing more beans each year before the bridge collapse were the ports of Newark, New Orleans, Charleston, Oakland, and Houston.

Compass uses imported sugar in addition to beans to make simple syrup. Their 12-ounce coffee bean cans are manufactured by a company that imports steel through the port.

Compass typically transports six to eight containers containing coffee and other products.

Once Compass beans are unloaded at the Port of Baltimore, they are trucked to a warehouse about 19 miles northeast of the city. The facility also stores beans from other coffee companies, from giants like Starbucks to small businesses like Washington, D.C.-based subscription service Kam's Kettle. Inside, 150-pound bags of coffee are stacked on wooden pallets.

The beans then wind their way to Compass' 18 D.C.-area cafes. Others are sent to wholesalers and grocery store customers, and some are sold to customers for home brewing.

The collapse of the bridge interrupted this process and meant, among other things, that coffee, sugar and cans had to be moved to a new location.

Some of the ships carrying beans were already at sea when the bridge collapsed, and shipping companies diverted them to New York and New Jersey ports in the Newark area. The port typically handles about seven times as much cargo as Baltimore and accepts much of the cargo originally destined for Baltimore, a Port Authority spokeswoman said.

Compass then needed to decide where to deliver the beans that had not yet been shipped. Matt Brown, who works with Compass as an outside sales manager for importer Café, said the company depends on factors such as the size of each port, its capacity to accept cargo, the cost of transporting the product from there to Washington, D.C., and the timing. It is said that they considered it. Imported goods.

Haft decided to send the coffee to Newark. While this solved the immediate problem, it also caused a domino effect.

The beans now enter the country through New Jersey, so it now takes five days to truck them to a warehouse in Maryland instead of 30 minutes. In addition, Compass must return the empty container to Newark. Chas Newman, Compass' chief operating officer, said sugar is also expensive to transport from New Jersey because it is dense.

Roaster's next order for bulk raw materials The coffee bags are expected to take 12 weeks to ship, twice as long as usual, and other shipments are also behind schedule. Empty simple syrup bottles were delayed by six weeks. One of Compass' main packaging suppliers, based in Maryland, also expects delays.

What does this mean for you in Washington DC?

For now, Compass is keeping prices the same for customers. However, Haft hasn't ruled out future price increases and would like to see the Port of Baltimore fully reopened before making any changes to operations.

The conversion cost a lot of money. It used to cost Compass about $1,000 to ship a container from the port to its roastery in northeast Washington.

The company currently plans to pay $3,500 per container for the trip from Newark to Washington, D.C., plus an additional $10,000 in sugar costs over the next three months. Haft sometimes buys more beans at a time to compensate for the time it takes to transport the coffee to the warehouse.

There are still other products that could be affected, from paper cups to compostable straws. “The ripple effects are being felt up and down the supply chain,” Haft wrote in an email. “We are scrambling to find alternative products and alternative transportation routes.”

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers said it aims to complete the removal of Key Bridge debris by the end of May, paving the way for the reopening of the Port of Baltimore.

“I hope so,” said Carl Bentzel, commissioner of the Federal Maritime Commission, which regulates international shipping. “But there’s a lot of steel that has to come up from the bottom.”

Edited by Kanyakrit Vongkiatkajorn and Tara McCarty. Illustrations by Hannah Good. Design editor: Christian Font. Photo editing by Mark Miller. Data compiled by Megan Heuer. Copy edited by Briana R. Ellison.

Photo by Craig Hudson for The Washington Post. Photo courtesy of Compass Coffee and images from marinetraffic.com used as illustration reference.