In the press release, Crawford speaks of her love for a skinny, spicy Casamigos margarita: “A few years ago, Rande and I were watching the sunset and we talked about how fun it would be for me to do a spicy tequila. Voila — Casamigas was born.” (Also, how fun is it to eavesdrop on completely authentic golden-hour conversations between hot model spouses?)

The other bottle is an additive-free blanco from Pure Brands, a U.S.-based investor-developer, named Not A Celebrity Tequila.

That a new tequila markets itself around what it is not should give you a hint of where we are these days. You can’t swing a quiote without hitting a tequila brand that’s owned, invested in or fronted by a celebrity (often the face of a multinational corporation). A by-no-means-comprehensive list includes Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson (Teremana), Kendall Jenner (818), LeBron James (Lobos 1707), Michael Jordan (Cincoro), Mark Wahlberg (Flecha Azul), Guy Fieri and Sammy Hagar (Santo, but Hagar also launched Cabo Wabo back in 1996).

“Having spent the last 4 years working in the tequila industry, it feels like every brand that has been released in that time has some sort of celebrity affiliation,” Pure Brands founder Andrew Bushby said in an email. While Not A Celebrity Tequila’s name is tongue-in-cheek, he hopes it has a more serious effect: encouraging more transparency within the industry, so consumers can make more educated decisions.

It’s going to be an uphill climb. Though the small, four-digit NOM indicator on every bottle of tequila or mezcal allows savvy consumers to find out some information about its production, labeling regulations for agave spirits are complex and often opaque, even to those steeped in the industry.

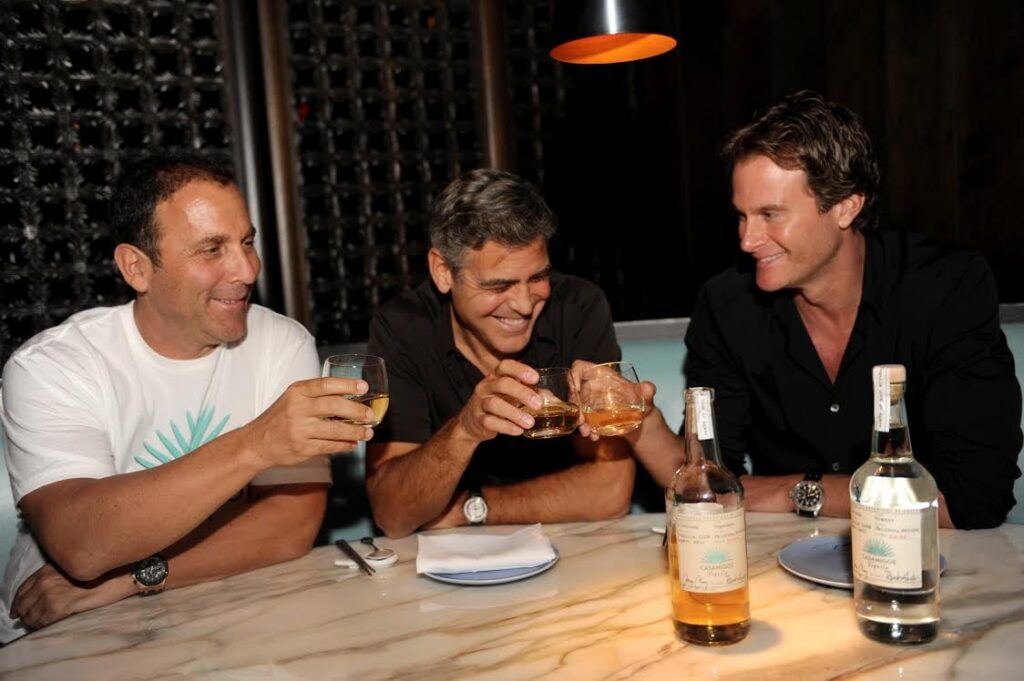

The category is getting crowded. Especially since that billion-dollar Casamigos sale, there’s been the booze equivalent of a Gold Rush.

“I’m honored to be known as the ones who helped grow the tequila category to what it is today,” Gerber said, in a statement sent by the Casamigos PR team. “Many will learn that it takes time, dedication, most of all it takes authenticity and a really great product such as Casamigos and Casamigas to succeed.”

Others have a different take. “Every celebrity pretty much since George Clooney has gone into not just mezcal or tequila, but any liquor, with dollar signs in their eyes,” says Susan Coss, co-founder of Mezcalistas, a company dedicated to raising mezcal awareness in the United States. Celebrity marketing is so pervasive that nobody cares “if you’re a celebrity and you start a vodka brand or a gin brand,” she said. “But I think as soon as you start playing in waters that are cultural, that’s where you get into trouble.”

Consider the backlash when Kendall Jenner — whose very Kardashianness guarantees an outpouring of love and hate for any project she might take on — launched 818 tequila, naming a Mexican spirit after an L.A. county area code, with images of herself riding a horse through misty agave fields dressed in vaguely “Mexican” apparel.

More subtly and pervasively, I’ve lost track of how many tequila websites contain a first-person celebrity origin story that goes something like: “I fell in love with this wonderful, authentic Mexican spirit, the vibrant history and culture it comes from, so I made a version that is way better than what they’ve been making for centuries.” The attraction to tequila may be sincere, but the marketing hook is baited with condescension.

If you distill it, will they come?

That’s the question for so many spirit brands, and a famous face can provide visibility in an incredibly crowded space.

“But a lot of celebrities miss that tequila and mezcal is something that is truly embedded in the culture of Mexico,” says Lucas Assis, former L.A. bartender and now a consultant and agave spirits educator. “It’s not just a spirit. It’s always more than just that.”

When American celebrities become the face of a spirit made by Mexican farmers and distillers, when they benefit financially from a spirit made from a plant with deep roots and cultural significance in Mexico, it raises the question: Who defines tequila? Its makers, its drinkers – or its marketers?

Tequila’s drinkers are disproportionately Americans. Since 2002, according to the Distilled Spirits Council of the United States, domestic tequila sales have grown by 180 percent; and the U.S. is still by far the biggest destination for tequila exports. Eighty-five percent of tequila is consumed in the U.S. and Mexico, with the U.S. vastly outpacing its southern neighbors, who actually make the tequila we drink.

American tastes have, for years, driven the evolution and marketing of agave spirits.

Worth billions, from a financial perspective tequila is a huge success story. It’s also a story about how consumers can alter the very product they seek. “Tequila historically was really just another mezcal, a mezcal from the town of Tequila way back when. Already what we know as tequila today has been completely shaped by the American market and the American palate,” says Chantal Martineau, author of “How the Gringos Stole Tequila.”

By law, mezcal or tequila can be made only in Mexico. Both are made from the spiny succulent agave, but tequila can be made only with one of the hundreds of agave species – tequilana (blue Weber) – and only in specific parts of Mexico. Mezcal allows for a wider range of agave species and locations. Agave plants are harvested by skilled jimadors, trimmed down to their piñas — imagine an enormous pineapple — and then cooked, crushed, fermented and distilled.

For Mexico, tequila’s explosive growth has been an economic boon, but it has also created tremendous pressures. Because blue Weber agave takes at least seven years to mature, as demand for the spirit has grown, some producers have sought to speed the process — using more land for growing, harvesting immature plants, using more efficient industrial cooking processes.

While some tequilas are still made by traditional methods, many have become what agave geeks refer to as “agavodkas” — industrialized versions that, for reasons of efficiency or cost, have been stripped of their essential character, often leaning on such additives as vanilla and glycerin to compensate.

Many of the tequilas fronted by American celebs land in this category. But the language on bottles can be a bewildering combination of flash and fact, making it hard to tell what you’re getting. Casamigos hints at added flavoring, touting “notes of a smooth vanilla finish” on its label. Many brands with similar notes don’t acknowledge any additives (and in aged tequilas, some vanilla notes come from barrel aging). But if you compare their flavors to a classic, truly additive-free tequila, your palate will tell you what’s going on.

Plenty of celebrity tequilas that lean smoother and sweeter are beloved by consumers. And so what? If you like a tequila that tastes like vanilla-frosted birthday cake, what’s the harm?

Maybe not much. But if millions of consumers believe that’s what tequila is supposed to taste like, driving other brands to follow suit, tequila will move farther and farther from its roots.

It’s not that celebrity-affiliated tequilas are never high-quality, says Bushby. The danger “is that a lot of the time the celebrity is not an expert … Many tequilas on the market are much lower quality than advertised or priced, have been made with agave in various stages of ripeness and have been artificially flavored or manipulated … to give the appearance of time and technique.”

I’ve been struck by how many brands seem to want it both ways: They have the celebrity face on the bottle, their website, the events, but they do not want to be thought of us as a “celebrity tequila.” Casamigos “was never a celebrity tequila,” according to Gerber. “George just happened to be an actor.” (It’s a paradox: so many celebrities “making” tequila, yet none of them make celebrity tequila!)

Beyond the question of whether celebrity tequilas are good lies a bigger question about their impact.

Celebrity marketing has helped push tequila’s enormous growth, but the wealth has generally not made its way to the people doing the hard labor to make tequila, says David Suro Piñera, a tequila importer, activist and co-author of “Agave Spirits.”

“I would love to have celebrities who actually share the profits,” says Suro Piñera, who also founded Siembra Spirits. “But if you come down to the farms in Mexico and ask most of the jimadors or people at the distilleries if they really see any increase in income? The answer is going to be not really.”

You can see this, he says, in the migration of jimadors leaving Mexico to seek a better living in the U.S., taking their skills with them. “If we don’t take care of the people who take care of tequila, there will be nobody to take care of tequila,” says Suro Piñera.

Many mezcal producers who have seen the path tequila has traveled want to protect mezcal — not from success, but from its side effects: increased industrialization of artisanal production processes, overplanting, and overreliance on particular agave species, the latter of which is problematic from a sustainability standpoint and also reduces the spirit’s incredible diversity and complexity. Celebrities sticking a toe into mezcal may find the water a little chillier.

Lupita Leyva, who used to work with the Mezcal Regulatory Council and now represents the Mezcal Ambassadors Project, recognizes that for mezcalero families, the opportunities of a celebrity partnership deal can be enormous. And she’s seen examples of celebs who seem to be trying to do things in a way that gives back to the region. She has high hopes for Dos Hombres, the mezcal launched by “Breaking Bad” stars Bryan Cranston and Aaron Paul, who have spent time with the family making their liquor, introduced a water project in the community, and seem interested in agave sustainability.

But, she told me in an email, other times celebs fly down in a private jet, go to the distillery, “grab a copita with water instead of a spirit, simulate drinking and eating local food, take 200 pictures, leave and never come back. For them [it’s] the same to own a tequila, vodka, whisky, panties, perfumes, blankets or some other brands,” she said. “At what point is it OK to sell our heritage, our culture to some people who do not appreciate it?”

“The fine, early aroma is off-dry and gently herbal, with a trace of honey backnote … the aroma blossoms into a harmonious, integrated bouquet … A classic distilled spirit that deserves your immediate attention,” wrote spirits authority F. Paul Pacult in “Kindred Spirits 2.” Five stars—his highest recommendation.

Sammy Hagar clearly likes tequila, but given the rep of celebrity tequilas, this review of his Cabo Wabo Reposado was unexpected. And I kept seeing begrudgingly positive reviews of Santo, his newer brand with Guy Fieri, on some sites where celebrity tequilas are generally excoriated.

Now 76, the former Van Halen frontman has been in the tequila game for nearly 30 years. Back in the ’80s, like most Americans and maybe especially most rock stars, Hagar had mostly tasted cheap mixto tequilas (in which up to 49 percent of the spirit may be made from sugars not from agave, typically sugar cane).

“I was one of those guys who said, ‘I can’t drink tequila anymore,’” Hagar says. Then while furniture shopping in Mexico, friends took him to Tequila and encouraged him to try a batch made by a local family. “All of a sudden, I’m pouring water out of my Evian bottle and filling it up out of a barrel—these guys had about ten—and I taste it and I’m like, ‘Oh my god.’ I’ve never had tequila like this in my life. This was a pure 100% agave handmade tequila, from ripe agaves, eight or nine years old, that these guys generally kept for themselves,” he says. “The light went on in my head.”

I was struck by Hagar’s sincere interest in the spirit, his unprompted voicing of the credos of serious agave people: Don’t use additives. Most celebs are in it for an ego-driven cash grab. Celebrity brands are catering too much to young American consumers who want drinks that are sweet and smooth. Tequila shouldn’t necessarily be smooth.

When he first worked with the Rivera family who made Cabo Wabo, he says, “I started with farmers that had donkeys and carts and they went out in those fields and got the agaves by hand, they had wood-burning ovens, they had one tank at the distillery, it was so small and they lived in little shacks. When I sold Cabo Wabo to Gruppo Campari, they all had beautiful mansions with swimming pools, they had trucks, and they had quadrupled [the size of] their distillery and they were very, very happy. They became millionaires.”

Do you feel a little misty at the loss of a rustic, authentic, traditional Mexican process disappearing due to an influx of American rock-star capital?

Me too. But I’m not the beneficiary of said wealth. It’s not my family’s future. And one of the great complications of agave spirits is that what’s “good” for sustainability, what’s “good” for quality tequila, what’s “good” for the preservation of traditional, artisanal processes and what’s “good” for the financial security of the people making agave spirits are sometimes in tension.

In many ways, this is arguing about the barn door after the burro has fled. Agave spirits have already been transformed by foreign investments.

But celebrities who choose to wade in can use their clout by focusing on high-quality, authentic spirits that respect the tradition, being aware of the cultural context and ensuring that profits and glory are shared with the people who truly make the liquor.

Or they can go the other way. (Taylor Swift, if you’re reading this, choose wisely.)

Agave spirits should compel consumers to ask themselves: Do I care only about what’s in the bottle? Whose name and face are on it? Or about how it got there? Do I care if the people making it can afford health care or feed their families? Does it concern me if they’re planting and harvesting agave sustainably?

Learning about all those factors, though, remains a challenge, and is more of an investment than most drinkers, aiming to grab a bottle for decent margaritas, are prepared to make. When I ask Suro Piñera if there are quick ways for someone standing in the tequila aisle to know whether they’re buying a “good” brand, he laughs ruefully.

“This is the question of my whole career,” he says.

Sammy Hagar is willing to advise. When I ask the Red Rocker for his tips for consumers wanting to make better choices in their purchases of agave spirits, he laughs, too. “Don’t buy celebrity tequila,” he says.

He doesn’t mean his, of course. That’s different.