Oakland city officials have been unable to collect tax revenue that could run into the tens of millions of dollars for years. With the city facing a crippling budget deficit that will likely lead to layoffs and service cuts, city and union officials want to know “what went wrong?”

The issue emerged last month after city councilors asked the Treasury how many businesses had not paid their taxes in the past three years.

In response, treasurers revealed that thousands of businesses have defaulted on tax payments since 2021. An April report showed as much as $34 million in taxes went uncollected. Forecasting, city staff predicts Oakland will collect more than $115 million in business taxes for the 2023-2024 fiscal year, which ran from July of last year to the end of June. This is 7.6% lower than the city originally expected.

City officials say last year's ransomware attacks were largely due to delays in the process of notifying businesses about delinquent taxes. The attack was carried out by a shadowy group of hackers who stole large amounts of city data, locked Oakland out of some of its systems and databases, and demanded that Oakland pay a large ransom. The city has not explained how it resolved the hack.

The City Treasurer answered technical questions from the City Council regarding the City's business tax collection process and schedule. But staff say they have no idea how many businesses are delinquent or how much money has been collected over the past three years, citing limitations in the multi-step process and software for notifying taxpayers of unpaid invoices. It points out that it is difficult to provide simple numbers on what is happening and what is not. .

City officials said Tuesday that the $34 million figure represents a snapshot of delinquent accounts on a specific day in April 2024. They stressed that the amounts are likely to change daily as payments come in and officials discover business failures. exist longer. The administration also said the $34 million is spread over three years and is a relatively small portion of the City of Oakland's $2 billion annual budget.

A city spokesperson acknowledged that the department's processes for investigating and collecting delinquent business taxes could be improved. For example, the agency is working to speed up the process of sending notices to delinquent accounts. When asked why the city has remained delinquent for years, a representative from the city administration said it can be difficult to determine if a business is still operational. It is unclear how much of this potential revenue will be recovered, but it is unlikely that the funds will go toward the current deficit, which must be resolved by the end of June.

A sense of crisis as the deadline for approving budget amendments approaches

City Council President Nikki Fortunato-Bass said they would identify and collect unpaid revenue not only for long-term financial stability, but also to offset potentially painful cuts to Oakland's workforce. He said it was important for the city to do so.

“Every $1 million in unpaid revenue that we successfully collect allows us to retain several city employees to provide the services we have to provide to Oakland,” Bass told Oaklandside. .

Councilor Janani Ramachandran has scrutinized Treasury reports and records and questioned officials at several meetings. Ramachandran believes the maximum amount left on the table could be as much as $50 million.

“There was a failure in leadership and decision-making,” Ramachandran told Aucklandside. City officials said they did not know how Mr. Ramachandran came up with the $50 million estimate.

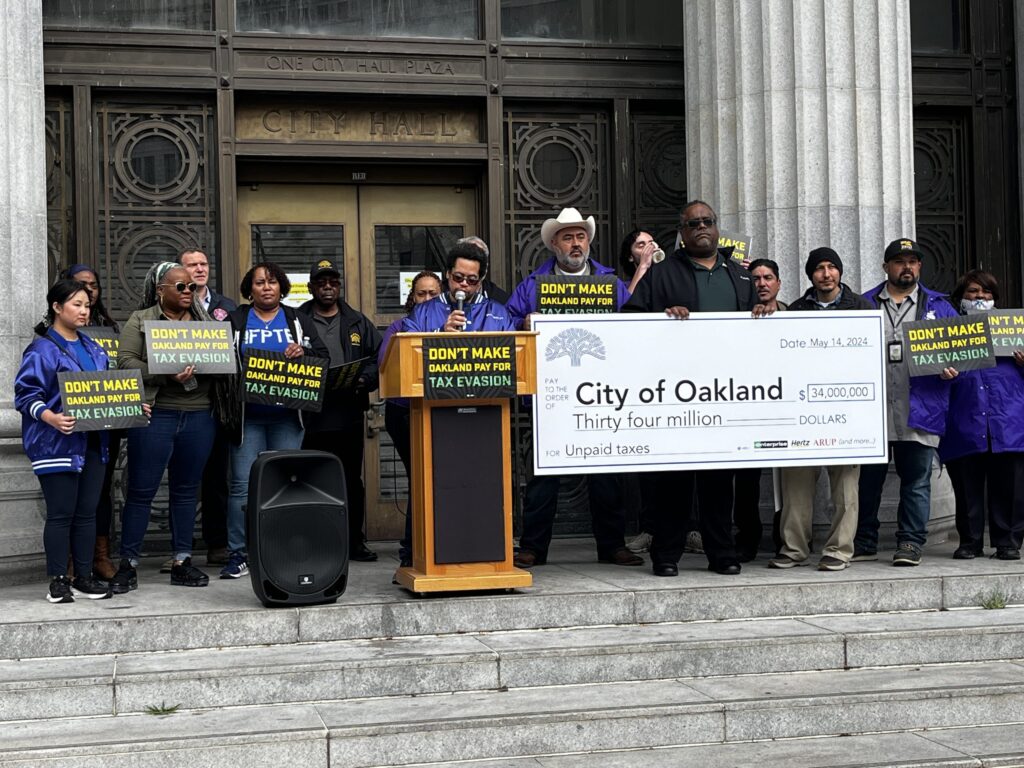

Ramachandran is not alone in this assessment. On Tuesday, Oakland's main union representing more than 3,000 workers, including firefighters, police dispatchers, engineers, service industry and electrical workers, gathered in front of City Hall to demand answers.

“Our message is simple: Don't make Oakland pay for tax evasion,” said Julian Ware, IFPTE Local 21 Oakland vice president. “We urgently need clear action and accountability from Finance Director Erin Roseman.”

Auckland Mayor Shen Tao has not yet announced any revised budget proposals, but it is widely expected that cuts will be imposed across multiple departments. The pink slip will likely be combined with cuts to critical services to offset an expected $177 million deficit in the city's general purpose fund.

“I haven't seen this budget yet, but I have a good idea of what's in this budget, and it includes fire department closures — a lot of fire department closures,” Oakland said. said Zach Unger, president of the city's fire union and a candidate for city council. Mr Unger told the Oakland Side that he expected three to four fire stations would be closed.

This year's deficit is primarily due to shortfalls in several key revenue categories, including business license taxes. In a letter sent to the mayor last week, labor officials said they met with City Administrator Jestyn Johnson in December after hearing from union members that the city was failing to take several steps in the tax collection and delinquency process. He said he did. Union officials said Treasury officials had given answers that were “often evasive or sometimes contradictory or false.”

Local 21 filed an unfair labor practice complaint against the city on March 25, alleging that employees violated the collective bargaining agreement by failing to consult with the union about financial plans that could affect the workforce.

In response to requests for information, union leaders said the city “either gave vague and undetailed answers, or told union members that work was being done only to confirm that no work was actually being done.” “I was assured that there would be,” he said.

Union representatives who spoke to The Oakland Side said the city's struggle to collect business taxes appears to be a relatively new problem.

City Council struggles to get clear answers

Ramachandran and Basu asked Finance Director Erin Roseman and Revenue and Taxation Administrator Sherry Jackson for specific data on revenue collection.

“We want to be as proactive as possible on the revenue front,” Council President Nikki Fortunato Bass said at the May 7 meeting, citing the budget deficit.

Bass asked how much unpaid revenue the city could collect and by when. Roseman responded that the city's collection cycle is continuous and extensive and takes into account penalties and interest.

An April 26 Treasury report found that “potential unpaid amounts” from fiscal years 2021-2022 to 2023-2024 could be up to $34 million from more than 21,600 companies. be. However, the report warns that some businesses included in the count may have closed or ceased operations in Auckland but not notified the city.

Councilors wanted the Treasury Department to come up with a total number of businesses deemed to be in arrears over a three-year period. In a memo published earlier this month, the Treasury Department said this would be a “custom query” that would cost Oakland money to run. “On the other hand, if staff manually retrieved the data, it would take months to compile and analyze it.”

In the same memo, the ministry said it would respond by sending delinquent businesses a notice demanding payment or requiring them to prove they had closed or relocated from Auckland. Bass said it's important to make sure all notices have been sent, as many businesses will pay out after they receive the notice.

Treasury officials said the ransomware attack meant they could not start sending out notices until October 2023, six months behind the normal schedule for business tax collection and four months after the end of the fiscal year. The city administration said the Treasury Department's notification dispatch process was significantly affected by the attack.

Ramachandran said candidly that he believes the Treasury Department is not speaking up to the City Council on the city's revenue issues.

“I feel like there is a reluctance to paint a picture of Congress, and I think that's the problem,” Ramachandran said.