By McGregor McCance

In 1983 Ed Freeman was a young university researcher and lecturer barely off the starting line in his academic career. Though he had produced plenty of papers about business issues, that summer would see the publication of Freeman’s first book: “Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach.”

He didn’t exactly expect it to set the world on fire.

“Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach” was published in 1984.

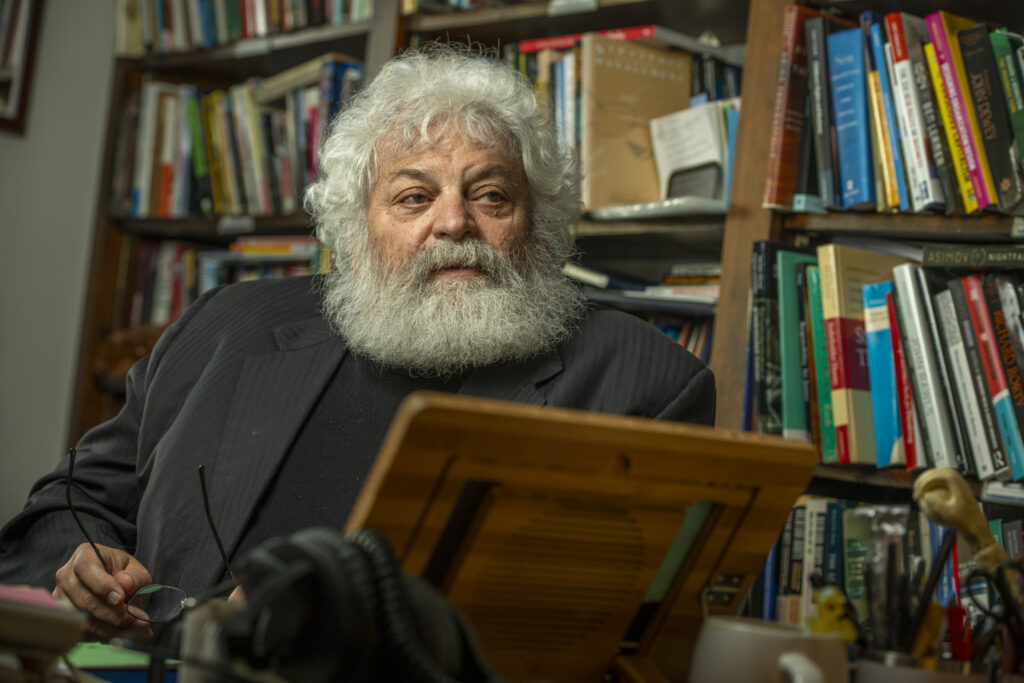

“My expectations were, ‘Look, I’m just trying to write something that says I really think companies are better off if they run their businesses for their stakeholders, not just their shareholders,’ ” Freeman said in an interview in his office at the University of Virginia Darden School of Business, where he’s taught the principles of that core philosophy, ethics, leadership and related topics for more than three decades.

Stakeholder theory holds that businesses exist to do more than just make profits and money for shareholders. Instead, they function best and serve the greater good when their actions reflect what’s best for all stakeholders – employees, suppliers, the community, partners and, of course, shareholders.

“It’s a business for human beings rather than business for a few human beings,” Freeman said. “I think that’s a better way to think about business.”

Freeman hoped the book would help him get tenure one day. He thought it might be useful for academics and corporate managers. He never expected to make money from it. Forty years later, what’s broadly known as stakeholder theory or stakeholder capitalism carries more weight than anyone might have imagined.

High Level Impact

Embraced by some of the country’s biggest corporations and many influential leaders, the concepts articulated in “Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach,” and refined and expanded in subsequent writings by Freeman and his colleagues, enjoy global acceptance. Leaders at corporate giants like Costco, Wal Mart and Whole Foods endorse them.

“Ed’s 1984 book was a watershed moment because it helped turn the tide and helped us see business as a deeply human institution.”

Bobby Parmar, Professor of Business Administration at Darden

In 2019, more than 200 CEOs affiliated with the Business Roundtable officially adopted a new “Statement on the Purpose of a Corporation.”

In it, the Business Roundtable officially moved away from the long-held and widely accepted narrative that the existential purpose of a business is to generate economic returns for its shareholders and instead embraced the stakeholder approach. The CEOs declared: “Companies should deliver long-term value to all of their stakeholders – customers, employees, suppliers, the communities in which they operate, and shareholders.”

Over the years, probably no economic idea has become more synonymous with Darden or its guiding values. “Stakeholder” has become part of the School’s cultural fabric. While the term has a specific definition, it also has become shorthand for Darden’s teaching philosophy based on responsible business management and ethically grounded leadership.

Bobby Parmar, the Shannon G. Smith Bicentennial Associate Professor of Business Administration at Darden.

“The success of stakeholder theory and Darden’s distinctive competitive advantage are tied together,” said Bobby Parmar, the Shannon G. Smith Bicentennial Associate Professor of Business Administration, who has known Freeman for nearly 30 years. “Ed has had a huge impact at Darden and helped us become a place that is unique and attracts students, faculty and recruiters who care about this set of ideals.”

A ‘Hero’s Journey’

If Freeman’s humility prevents him from accepting much credit, others are happy to assign it.

“All of us are called to a hero’s journey,” said John Mackey, co-founder and former CEO of Whole Foods Market, the natural and organic grocer that grew from a single store to 540 stores with $22 billion in annual sales and more than 105,000 employees. “Most people don’t answer that call. Ed answered it, and he’s a hero. He’s made a big difference in the world, and he’s a remarkable human being.”

Mackey’s journey through entrepreneurship and business leadership – and his (unknowing at the time) exposure to stakeholder theory – began in the mid-‘70s when he was living in a vegetarian housing co-operative. Those in the food co-op line of work didn’t focus much on profits. In fact, they were essentially anti-profit and mostly wanted low prices and broad access. But any notion to serve more people eventually ran into their aversion to profits. There simply was no money to invest in expanding the business.

Mackey took note. A business couldn’t truly flourish with just one objective or one group in mind.

In 1980, Mackey and his girlfriend Renee Lawson merged a young natural foods store they started together in Texas with another local store to establish Whole Foods Market. The company struggled after a disastrous flood nearly wiped it out in 1981. It survived because a banker personally guaranteed an emergency loan after the institution declined Mackey’s application. Whole Foods employees worked without pay for a month until payroll could get back on track. Suppliers fronted the company inventory to restock shelves.

“I began to realize, we are in this network of relationships, and they love us and care about us, and we owe them,” Mackey recalled. “We need to pay back the generosity they’ve shown us.”

By the early ‘90s, as both Mackey’s company and his own business acumen continued to mature, the CEO grew more interested in this concept that a business could improve the world by focusing on more than just profits. Another famous business book, “Ethics and Excellence: Cooperation and Integrity in Business,” deeply impressed Mackey. As it turned out, its author, Robert C. Solomon, and Ed Freeman were friends and philosophical brethren. Soon, Mackey began devouring anything Freeman had written on the topic.

The common thread connecting Mackey’s own experience, his business strategies and his personal values finally had a name: Stakeholder theory.

“I got excited about it because I realized, ‘Well, that’s it!’ That’s the term I’ve been looking for, what we’ve been doing at Whole Foods,” he said. “The brilliance of what Ed did is that he saw the interdependencies. He saw it as a system, and it wasn’t seen that way before Ed came along.”

Stakeholder Vocabulary

Parmar credits Freeman for clearly articulating this approach to running a responsible business, and for a providing a “vocabulary” that cut against a narrative that dominated since economist Milton Friedman’s famous 1970 New York Times commentary. In it, Friedman stated that the only social responsibility of business is to increase its profits as long as it does so legally and in open competition. While “Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach” shared some terms and concepts you’d find in any economic writing of the day, it spoke an altogether different language for businesses.

“Ed’s 1984 book was a watershed moment because it helped turn the tide and helped us see business as a deeply human institution,” Parmar said.

Not that it immediately changed things. That would take time.

Andy Wicks is the Ruffin Professor of Business Administration and director of the Olsson Center for Applied Ethics at Darden

Andy Wicks witnessed the evolution. Wicks is the Ruffin Professor of Business Administration and director of the Olsson Center for Applied Ethics at Darden. He’s taught here for 22 years, and before that, was a UVA religious studies graduate student focused primarily on medical ethics, followed by a decade teaching at the University of Washington. He met Freeman in the late ‘80s, soon after learning about stakeholder theory.

Wicks recalled having his students in a 2002 class read an article by Milton Friedman (companies exist to create shareholder profits) and another by Ed Freeman (all stakeholders are integral). In a class of 70, only one student raised a hand to indicate alignment with stakeholder theory.

“When I teach that material today in a Darden classroom, I will get anywhere from 60% to 80% of the students who raise their hand for Ed,” Wicks said.

Origin Story

Spreading the word has proven to be a lifelong passion.

During his career, Freeman has written and co-authored hundreds of books, articles, commentaries and essays about stakeholder concepts and the importance of business ethics. He’s taught thousands of students. Accepted honorary degrees across the world. Provided countless media interviews. Freeman travels frequently to deliver guest lectures at business and management schools, participate in conferences about responsible business practices and management, and consult directly with corporations.

The concepts have come a long way since he first was exposed to the idea of business “stakeholders” at the Wharton School of Business in the mid- and late-‘70s. Even before then, Freeman has stressed over the years, researchers at the Stanford Research Institute and a Swedish theorist were analyzing how different groups affiliated with or interacting with businesses could affect a company. Recognizing those pressures and influences was part of being strategic. Those pioneering researchers introduced the term stakeholder into the discussion.

But stakeholders at that time predominantly were considered disparate elements that could influence the operations or success of the company, rather than integral components or partners whose shared interests could enable them all to flourish.

“He’s made a big difference in the world, and he’s a remarkable human being.”

John Mackey, co-founder and former CEO of Whole Foods Market

That bigger idea “was in the air,” Freeman said. And during one Wharton gathering of economists and academics, the chalkboard featured a diagram of different stakeholders. Freeman remembered one person suggesting that it wouldn’t be appropriate to discuss the interests of those other stakeholders in the context of the corporation’s fortunes because their issues were matters of “justice” rather than strict business considerations.

“I’m just sitting there like a fly on the wall, probably 25 or 26. And I thought, ‘Well, wait a minute. I don’t know why you can’t say anything about justice.’”

Freeman didn’t voice his thoughts in that setting. But he and his boss at the time, Jim Emshoff, were thinking and writing together along those lines. Emshoff encouraged Freeman to further explore the idea of a stakeholder approach, to try to answer, “Can you run a business this way?”

“Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach” was about to be born.

A Most Awesome Feeling

Published in summer 1983 with a 1984 copyright date, only 2,000 copies comprised the initial run. (The book has been updated and reissued, and along with Wicks, Parmar and others, complementary volumes build on the original themes.)

Freeman remembers holding the book in his hands for the first time.

“It was, at that time, the most awesome feeling I had had professionally,” he said.

Evidence of stakeholder capitalism’s enduring influence abounds – whether it reflects Freeman’s specific contributions or the continued general recognition of the value of businesses that account for the wellbeing and success of its full set of participants.

In a report published in 2021, the Conference Board said its research and surveys showed that nearly 90% of C-suite executives surveyed around the world believed that “there is a shift underway from stockholder to stakeholder capitalism, and almost 80% say the shift is occurring at their firm.”

The organization reported increased focus among corporate leaders on environmental and social issues, diversity, employee wellbeing, workforce management and community impact. “Executives who recognize and embrace the shift now are better positioning themselves and their companies for success in the future,” the Conference Board suggested.

But it’s not time to declare victory by any stretch. Almost any edition today of the Wall Street Journal or other major news outlets will remind one that unethical or selfish corporate behavior will always come with the territory if humans are involved.

Mackey, though optimistic overall, said stakeholder theory faces threats on multiple fronts. On one hand, he said, a growing number argues that focusing exclusively on creating returns for shareholders will actually help all stakeholders in the end because they’ll share in or indirectly benefit from the profits. On the other extreme, he sees growing anti-business sentiment in some quarters, with groups seeking control of corporate boards to advance narrow agendas reflecting political priorities of the few, rather than the good of all stakeholders.

Mackey finds both approaches flawed and limiting.

“Stakeholder theory is being challenged on these different fronts,” he said. “But it works. If it didn’t lead to competitive advantage it would disappear.”

Freeman, too, conveys optimism. However, he identifies authoritarian political movements as a threat to approaches like stakeholder capitalism because they can lead to crony capitalism, in which the government skews a functioning competitive marketplace by getting involved in ways that favor specific businesses or industries.

“If you pay attention to stakeholders, and you have a high purpose, you’re basically going to beat the hell out of companies that don’t, unless these companies get a leg up from government. So that worries me.”

A Task Not Yet Finished

His continued experience in the classroom particularly heartens Freeman. Students come to Darden with a strong appreciation of the importance of business ethics. It could be that many choose Darden today because of its reputation for teaching and emphasizing ethics – and that suits him fine.

“They come in with a stronger sense that they want to do something that has meaning,” he said. “They want to do something that makes the world better. There’s no question about that.”

Two years ago, as his book was nearing 40, Freeman reassessed how well it has stood the test of time in “My Own Book Review. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach,” published by the International Association of Strategic Management.

One of the book’s enduring strengths is that “it is based on real business situations, and it does not shy away from prescribing how business can improve,” he wrote. Among the weaknesses: a chapter focusing on internal stakeholders, which Freeman later recognized as a potential distraction from his goal of making businesses more cognizant of external stakeholders.

He also linked the heart of the theory and practice to core values – such as those he earned and learned growing up on a Georgia farm – especially the truth that “one needed to be responsible for the effects of one’s action on others.”

“I get far too much credit for a very small role that I played in developing the stakeholder idea,” Freeman concluded in his humble and self-critical review. “But the task is not yet finished. We desperately need to hasten the transition to a more inclusive stakeholder capitalism. That is a worthy task for our generations, and one to which I am committed.”