scratch

“I try to make people feel good.” How one New Jersey diner stays in business.

Julia Rothman and

Julia is an illustrator. Shaina is a writer and filmmaker.

Just after 5 a.m. on a recent Friday, Bendix Diner, a small, family-run establishment, began frying eggs on a hot plate, the first of dozens of dishes it serves to a rotating cast of regulars.

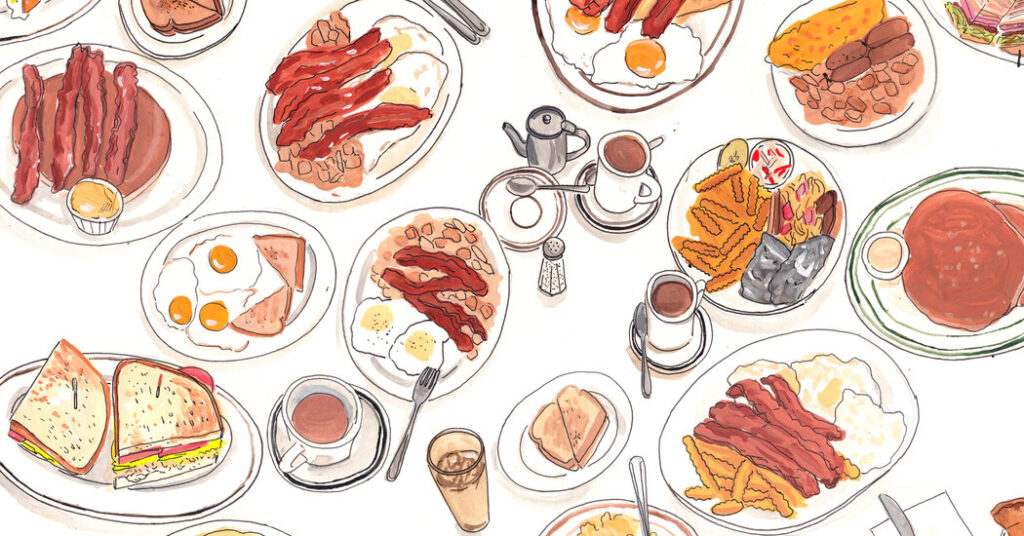

From dawn until lunch, 46 guests ate more than 87 eggs, 36 slices of bacon, and drank copious amounts of coffee. This classic diner in Hasbrouck Heights, New Jersey, just 15 miles from Manhattan, offered a glimpse into many of the things shaking up the country right now.

Amid the sounds of cooking and televisions blaring court cases, people could be heard lamenting the rising prices of gas and goods. Some debated who should be the next president, while others discussed marijuana laws.

The one thing that hasn't changed is the sense of community diners feel here and its owner, John Diakakis, a 56-year-old blind man whose family has run the restaurant since 1985 (though the restaurant itself has been around since the 1940s).

Though blind, Diakakis keeps busy serving food, refilling drinks, handling money, and more. He is assisted by his three sons, who help out on weekends, Julio, a longtime cook, and a small team of part-time dishwashers named Tiny (who is well over six feet tall).

Regular customers, most of whom are men and many of whom have nicknames, let Diakakis know in advance who is coming and bring their dirty dishes to the kitchen.

“The place makes a good income, but running a diner is hard work,” Diakakis said.

Running a small shop like Bendix has always been precarious: weekdays are hit or miss, he says, and weekends are busy (the shop regularly goes through 1,000 eggs), but it's gotten tougher in recent years as rapid inflation has made operating costs unpredictable.

“Since COVID, a lot has changed. Things change every week. Until recently, a case of eggs was twice as expensive, but when news of bird flu comes out, the price of a case can go up to four times,” Diakakis told me about the menu, recording every meal ordered that morning.

New Jersey has long boasted a reputation as the diner capital of the country. Peter Sederears, who owns a diner in New Jersey and runs an informal diner coalition, said the number of diners in the state has declined in recent years. “We don't keep an official count. It's just growing by word of mouth. At our peak, we had 575 diners; now we're at about 400.”

The Diakakis have scrambled to adapt, adding vegetarian options to their menu and hosting film shoots to bring in extra cash. “We're going to try DoorDash and Uber Eats this summer. We have to make sure we're on deck,” Mr. Diakakis says. “Things change. We have to evolve.”

Bendix continues to evolve, but its enduring appeal lies in the nostalgia it exudes.

But customers also like to talk about current events in a country that feels constantly at war. Regulars come from all walks of life and across party lines. “The Fox News and CNN parrots are arguing on the counter. I try to stay out of politics,” Diakakis says.

Customers like Khaled Mohammed, 49, a professor and aeronautical engineer, are also feeling the financial pressure.

Walter Martin, 59, is the owner of a limousine service. He's known as Limousine Walt. He first set foot in Bendix 13 years ago.

These days, places like Bendix are under pressure on multiple fronts: rising raw material costs, rising property taxes and competition from food-delivery apps that have become an essential part of daily life. Restaurants have to offer something special to lure diners out.

For police officer Dominique Cebolero, 30, and her mother, Mary, 70, it was the atmosphere at Bendix that made them decide.

After all, this is Diakakis' (special) skill: he fosters community, he creates an environment where people care for one another. In a world that often feels cruel, Bendix Diner is the polar opposite.

“We've been raising our food prices for almost two and a half years now,” Diakakis said. “I don't mind raising the prices a little bit because I want my customers to feel good. I want them to laugh, to eat, to have the experience of being blind.”

“They're not walking out of here saying, 'Why the hell did you come in?'”