The concept of using polls to predict the outcome of presidential elections is centuries old, but the procedures employed have evolved over time.

Today, “elections and opinion polls are so intertwined that it is difficult to imagine one without the other. Polling numbers feed media coverage and election predictions, shape the behavior of candidates and voters, and provide the basis for interpreting the meaning of election results,” as D. Sunshine Hilligas writes in Public Opinion Quarterly.

The history of measuring public opinion has gone through several stages. Before representative government, royals and monarchs had no reason to measure the opinions of their people. As democracies emerged in the United States and other countries, leaders sought to find out what people cared about and what their partisan preferences were.

Early American officials constantly worried that the public would criticize their policies: “George Washington in particular sought feedback on what he considered to be flaws in his actions more than on what he considered to be praiseworthy,” Lindsay M. Chervinski wrote in Lapham's Quarterly.

Washington and other early politicians tracked the issues, concerns, and mood of the nation through a wide network of friends and acquaintances. They monitored pamphlets, letters to the press, and rallies, which frequently described popular sentiment. Washington held weekly open houses and sometimes rode through the countryside on horseback, asking people he met their thoughts about government.

The first political survey was conducted during the 1824 presidential election.

Reporters from the Harrisburg Pennsylvanian interviewed residents near Wilmington, Delaware, asking them about their favorite candidates in a non-scientific sampling survey known as a “straw poll,” so named because of the suggestion that such votes, like straws tossed in the air, would “show which way the wind is blowing.” The poll correctly determined that Andrew Jackson had won the popular vote, but a runoff election in the House of Representatives for electoral votes awarded John Quincy Adams the presidency.

The successful prediction was pure chance, due to flaws in the tabloid's polling methodology, which “only counted available respondents, typically excluding hard-to-track demographics like the poor and working class,” Jackie Mansky wrote at SmithsonianMag.org.

Over the next century, primaries for presidential elections became common.

Publications across the country organized their own polls and also reported on those conducted by others. In many cases, the bogus tallies strangely far exceeded the vote share of the candidate favored by the newspaper. “These polls were obviously intended for the entertainment of their readers and for partisan gaming…because primary polls cannot provide conclusive evidence of the outcome of an election,” Clifford Teece wrote in Presidential Studies Quarterly.

In the early 20th century, the popular Literary Digest magazine funded the first national primary for a national referendum for commander in chief, held every four years.

The survey methodology was based on the unfounded assumption that larger samples would increase the validity of the results. Its predictions were remarkably accurate, correctly predicting the outcomes of all five presidential elections between 1916 and 1932. “Opinion polls were a lucrative business for magazines; readers loved them, newspapers featured them extensively, and each 'ballot' included a subscription form,” according to a report on HistoryMatters.gmu.edu.

In 1936, the Digest's reputation for good prognostication took a beating. The magazine erroneously announced the winner of the election based on a mail-in survey of subscribers who had returned over two million postcard votes. The tally incorrectly predicted that Republican Alf Landon would win in a landslide victory over Democrat Franklin Roosevelt. The prediction's “failure was secondary to a flawed sample; the magazine's readers were well-off and not representative of the poor affected by the Great Depression.”

The Literary Digest debacle signaled the end of primary predictions. George Gallup, who had accurately predicted the outcome of the 1936 election, stepped in and changed the way presidential elections were predicted, ushering in the modern era of campaigning.

Gillian Brockwell of The Washington Post described his groundbreaking approach: “Rather than gauging the opinions of large numbers of the same type of people, Gallup developed a system of 'quota sampling' to survey a small number of Americans whose demographics reflect the overall population in order to get a more accurate measurement.”

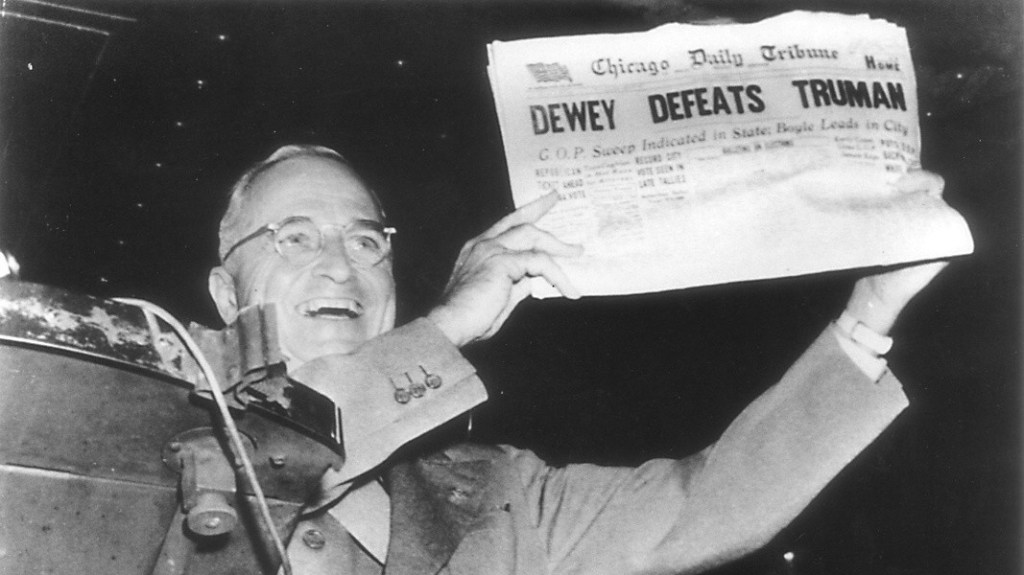

Gallup's company thrived with offices in 10 countries, and his work appeared regularly in over 100 periodicals. In 1948, the organization suffered a setback when it incorrectly predicted that Thomas Dewey would handily defeat incumbent President Harry Truman. This erroneous prediction led to premature headlines in many daily newspapers announcing Dewey's victory. Gallup's reputation was tarnished, but the organization weathered the disaster.

Over the next half century, Gallup, along with other polling companies, adopted new strategies to improve the accuracy of their forecasts.

In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, telephone polls and live interview surveys were the standard for input, but the advent of cell phones and the Internet changed the methods of accurate sampling. An article from the Pew Research Center states that “pollsters don't just use different methods, many use multiple methods” to reliably assess test groups for national polls. These new protocols gave rise to computer-savvy entrepreneurs who made their mark in the research industry.

Social scientists tell us that one of the most fundamental human desires is to peer into the future, as evidenced by the many opinion polls that have emerged since the first presidential election winner was predicted in 1824.

Since then, science has significantly improved the validity of polls, but experts acknowledge that it's still possible for the wrong candidate to be elected. Perhaps when in doubt, experts should just throw straws in the air and see how the political winds blow.

Jonathan L. Stoltz is a resident of James City County.