The Nashville Regional Chamber of Commerce has been hosting an annual conference of local business leaders since the 1800s, but the theme of a recent gathering was decidedly modern: artificial intelligence.

The goal is to demystify technology for the chamber's roughly 2,000 members, especially small and medium-sized businesses.

“I don't get the sense that people are wary,” said Ralph Schultz, the chamber's chief executive officer, “They just aren't sure how it will be used for them.”

When generative AI burst into the public consciousness in late 2022, it captured the imagination of businesses and workers with its ability to answer questions, compose text, write code and create images. Analysts predicted the technology would drive a surge in productivity and transform the economy.

But so far, its impact has been limited. Despite rising adoption of AI, only about 5% of businesses nationwide use the technology, according to the Census Bureau's Business Survey. Many economists predict it will be years before generative AI has a measurable impact on economic activity, but say change is coming.

“To me, this isn't a five-quarter story, this is a five-year story,” said Philip Karlsson Szlezak, global chief economist at Boston Consulting Group. “Are we going to see something measurable over a five-year period? I think so.”

While some larger companies in Nashville and elsewhere are finding uses for AI and investing money and time in further developing it, many smaller businesses are just starting to dabble in the technology, if they're not using it at all.

“Right now, the smartest and biggest companies are really implementing this and extracting value from it, but the adoption curve is still very early on,” Karlsson-Szlezak said.

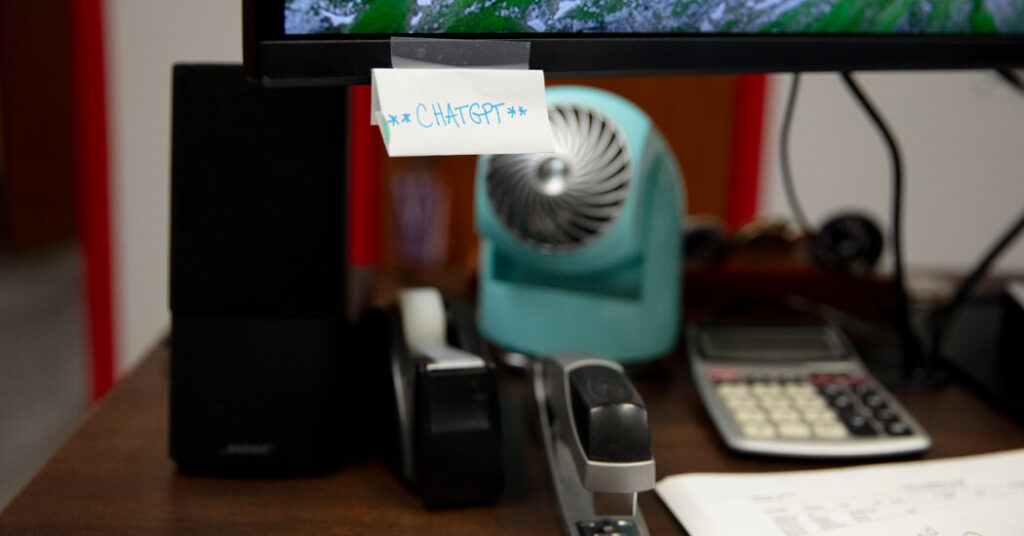

Allison Giddens, co-president of Wintec, a 41-employee aerospace manufacturing company in Kennesaw, Georgia, said she started using ChatGPT about six months ago for several job tasks, including writing emails to employees, analyzing data and creating basic procedures for her company's front office. She keeps a note on her computer monitor that simply says “ChatGPT” to remind herself to use the technology.

“You have to get into the habit of actually using the tools,” she said.

But there are hurdles to adopting it more broadly and using it to make her company more efficient. Sometimes, ChatGPT's answers feel off the mark. Cybersecurity is important in her industry, so she has to be careful about what information she inputs into AI models. And the technology wouldn't work on a factory floor, where machinists make custom aluminum and titanium parts for the defense industry.

“There aren't many examples of it being used in manufacturing yet,” she says.

Historically, technological innovations such as computers and the Internet have taken years, or even decades, to penetrate an economy and affect productivity and output. American economist Robert Solow noted in 1987 that “the computer age can be seen everywhere except in productivity statistics.”

Economists generally believe that generative AI will become more widespread and adopted much faster, in part because information flows more quickly than in the past. For example, in a recent series on generative AI, consulting firm EY-Parthenon concluded that the technology could improve productivity in three to five years.

But there are several significant barriers, including hesitation to use the technology, legal and data security hurdles, regulatory friction, cost, and the need for more physical and technical infrastructure to support AI, including computing power, data centers, and software.

“We're still in the early stages of the revolution in the sense that significant investments are beginning to be made to lay the foundations for that revolution,” said Gregory Daco, chief economist at EY-Parthenon, “but the full extent of the benefits in terms of productivity, in terms of increased output, in terms of expanded deployment of the workforce are yet to be seen.”

David Duncan, CEO of Chicago hotel operator First Hospitality, said the company is working to make its internal financial data available to AI systems in the future.

“We are planning the next generation of applications of AI,” he said.

Duncan said he envisions using AI to analyze this data and write early drafts of reports, reducing the burden on executives and general managers. The company, which has about 3,600 employees, also hopes to use AI to analyze weekly employee surveys over a year to gain insights into morale trends across the team.

“I think we're in the early stages of a massive transformation in how business ideas, strategies, data and output are processed,” Duncan said.

According to the survey, AI use is most prevalent in information and professional services, such as graphic design, accounting and legal services – traditional white-collar jobs that are less threatened by automation.

Research has found that marketing is one of the most common uses of AI across all businesses: Gusto, a payroll and benefits platform for small businesses, found that of companies founded last year using generative AI, 76 percent were using it for marketing.

Still, many economists believe that in the long term, there are few occupations that won't be affected by AI in some way. EY-Parthenon estimates that two-thirds of U.S. employment, or more than 100 million jobs, are affected by generative AI at a high or moderate level, meaning those jobs are likely to be transformed by AI technology. The remaining jobs, which typically involve more social and human interaction, are likely to be affected as well, through tasks such as clerical work.

And AI adoption appears to be gaining momentum. Using data from the Census Bureau's Business Establishment Statistics, a working paper from the Center for Economic Research found that there was a “significant, notable surge” in AI-related business applications last year, which could help drive adoption of the technology. The paper also showed that over the years, businesses born from AI-related applications have greater potential for job creation, payroll, and revenue than other businesses.

Taken together, “we believe these AI startups could have an impact on our economy in the near future,” said Can Dogan, an associate professor of economics at Radford University in Virginia and one of the paper's authors.

“In general, incumbents should find out what they can do with these technologies,” he added. “I think that's going to be the key to wider adoption.”

Chris Jones, founder of Planting Seeds Academic Solutions, an education and tutoring business with nine employees and 100 to 150 independent contractors, is also exploring how to use emerging AI technologies. Jones, who lives in Dallas, said he was interested in using AI at his company in 2021 or 2022, but “wasn't fully sure how it could be integrated into our business.”

He plans to hire a consultant soon to show the company how to use AI in sales, administration, curriculum development, and other program operations. He said he is aware of the potential impact on employees' jobs, but is clear about the changing economic climate.

“Competition is real and as a business you need to survive,” Jones said.

In Nashville, the driving force behind encouraging small businesses to adopt AI is Chamber of Commerce President Bob Higgins, who has been talking to other business leaders, hosting webinars and working with a Vanderbilt University professor who is an expert on generative AI.

Mr. Higgins is also trying to lead by example: At his engineering and architectural services firm, Verge Design Solutions, where he is CEO, the HR team is using generative AI to write job ads to attract more qualified applicants for hard-to-fill positions. He also uses the technology as a “thought partner” to prepare meetings and write agendas.

The ultimate goal, he said, is to “make Nashville a GenAI city.”

“I think if you live in fear of that, you're going to be left behind,” he said.