Five days before a federal jury found Hunter Biden guilty of felony firearms charges, President Biden publicly stated that he would not pardon his son. ABC's David Muir interviewed the president in Normandy and asked Biden if he had “ruled out a pardon.” Biden's response was quick and straightforward: “Yes.”

Indeed, Biden could pardon his son. The Constitution gives the president sweeping powers to “grant reprieves and pardons.” Subject to certain constitutional limitations, this power is among the most sweeping of the presidential powers.

But doing so would be an abuse of presidential power.

While the president should not be praised for declining to abuse his power, his decision stands in stark contrast to his predecessor, who pardoned friends, donors, staff and loyalists while considering what they might do for him in return. The Washington Post An investigation into the pardon laws during Trump's term concluded that “never before has a president used his constitutional pardon power to release or pardon so many people whose actions may be useful for future political activity.”

Biden's decisions, reiterated recently, help clarify the appropriate use — or lack thereof — of the president's core powers — and serve as a reminder of the president's solemn obligation to serve the nation's interests, not his own.

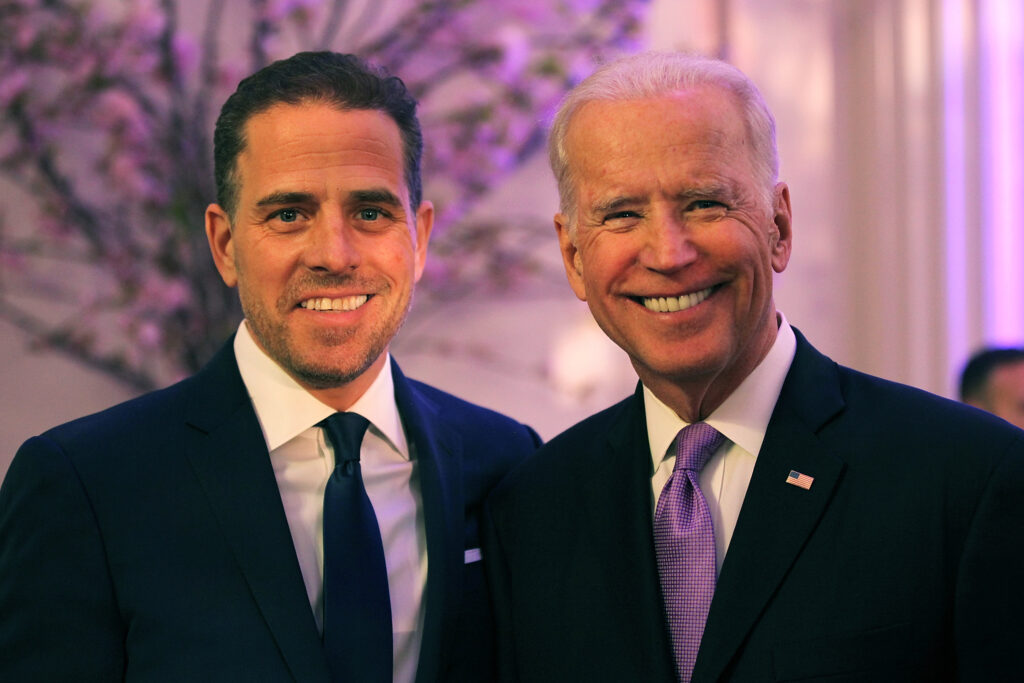

Teresa Kruger/Getty Images, courtesy of World Food Programme USA

In general, the United States Constitution commands the President to exercise his powers to promote the public welfare. Two clauses, the Duty of Care Clause and the Oath Clause, require the President to swear an oath to “take care that the laws be faithfully executed” and to “faithfully execute the office of the President.” According to legal scholars, when the Constitution was written, the term “faithfully execute” specifically meant exercising power in the public interest, not for “self-interest, self-defense, or any other malicious or personal reasons.” This is the only command to appear twice in the Constitution.

In including the pardon power in the Constitution, the Framers made it clear that, like other presidential powers, it would be used to promote the public interest. Alexander Hamilton explained the importance of pardons, given that the justice system would inevitably be “cruel and overly cruel” at times. He also envisioned their use during times of civil war, when “by a timely pardon to rebels and traitors, tranquility in the Union might be restored.” George Washington's first pardons were offered during the Whiskey Rebellion as a tactic to induce rebels to lay down their arms. (It worked, and pardons helped put down the rebellion.)

For most of American history, it was unheard of for a pardon to be used for personal reasons, such as to provide assistance to campaign donors or political activists.

In the rare cases where pardons have come before the courts, the judiciary has also reaffirmed its public interest role. In 1927, the Supreme Court explained that pardons are not “private pardons” but a means of promoting the “public welfare.” (Chief Justice and former President Howard Taft, who recused himself from the case, later wrote that he had granted the pardon in question.)[t]He just rules [a president] The only rule that must be followed is that it must not be exercised against the public interest.”

In 1974, federal courts devised a “public interest” test to evaluate the constitutionality of conditions imposed on a commutation of a sentence. The court explained that “the President, exercising his powers as the elected representative of the people, must at all times exercise those powers in the public interest.”

By refusing to pardon his son, Biden is simply complying with the scope of the pardon power as intended by the Framers and Constitution, which does not include using pardons for personal gain.

To be sure, Biden has pushed the boundaries of executive power in a variety of other areas. In 2022, he unveiled a plan to cancel hundreds of billions of dollars in student loan debt, relying on an expansive interpretation of the president's emergency powers. In 2023, he successfully defended the government's domestic mass surveillance program; as a senator, he called the law an “unconstitutional expansion of presidential powers.” The Biden administration also continues the practice of firing missiles at countries it is not at war with without congressional approval.

What makes the President's decision noteworthy in this case is not that it is a decision not to abuse presidential power. His decision not to pardon Hunter Biden should be seen as the kind of basic restraint we should expect from those entrusted to serve the people they represent, not themselves.

Grant Tudor is a policy advocate and Amanda Carpenter is editor of Protect Democracy, a nonpartisan anti-authoritarian organization.

The views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Rare knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom, seeking common ground and finding connections.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom, seeking common ground and finding connections.