A version of this story appeared in CNN’s What Matters newsletter. To get it in your inbox, sign up for free here.

CNN

—

With Democrats divided over the Israel-Hamas war, uninspired by their presidential nominee in Joe Biden and planning a convention in Chicago, there have been multiple comparisons to 1968, when Democrat Hubert Humphrey lost the White House to Republican Richard Nixon.

The Vietnam War divided Democrats that year. Humphrey was uninspiring to younger voters opposed to the war. There was violence outside their convention in Chicago.

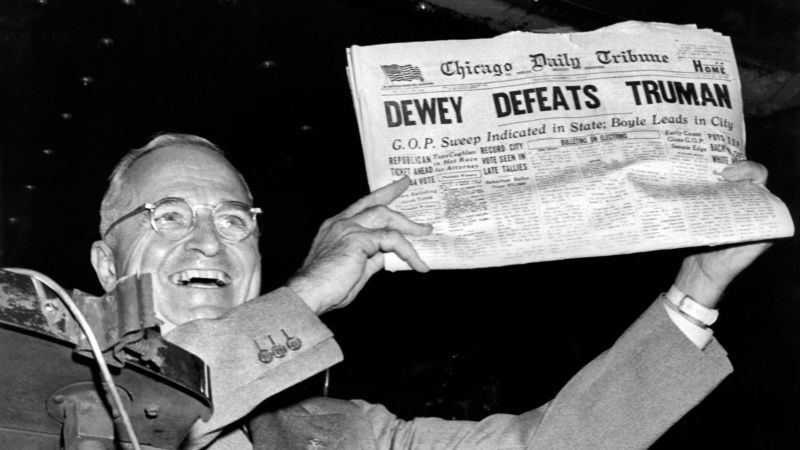

Democrats today should hope that a better comparison is to 1948, when then-President Harry Truman, an unpopular incumbent, pulled off a surprise reelection versus Thomas Dewey, then the Republican governor of New York.

That year, 1948, was also a much better year for Humphrey, then the young and inspiring Minneapolis mayor who helped push Democrats on the road to embracing civil rights legislation that would ultimately remake both political parties over the coming decades.

I talked to Samuel Freedman, a Columbia Journalism School professor, about his recent book about Humphrey and the 1948 Democratic convention in Philadelphia. The book’s title, “Into the Bright Sunshine,” is taken from a line in Humphrey’s rousing speech on civil rights. The crackling audio does not hide the competing jeers and applause when Humphrey says:

My friends, to those who say that we are rushing this issue of civil rights, I say to them we are 172 years late. To those who say that this civil-rights program is an infringement on states’ rights, I say this: The time has arrived in America for the Democratic Party to get out of the shadow of states’ rights and to walk forthrightly into the bright sunshine of human rights.

It is a particularly important time to remember right now, when there is an effort on the American political right to reinterpret the history of the Civil Rights Movement.

Here’s my conversation with Freedman, conducted by phone and edited for length and clarity:

WOLF: The fulcrum of the book is this 1948 Democratic convention and Humphrey’s civil rights speech there. Until 2016, 1948 was probably the biggest presidential election upset in US history. What could 2024 Joe Biden, who trails Donald Trump in much of the polling, learn from 1948 Harry Truman, who trailed Thomas Dewey right to the end?

FREEDMAN: They are very comparable experiences, even with the fact that Truman had not one third party, but two third parties also to worry about – Henry Wallace to his left and Strom Thurmond to his right. We don’t know about the effect in the tight election of RFK Jr., and even for that matter, of (the Green Party’s) Jill Stein. So Biden has a complicated course to run.

Truman went back and forth on civil rights – he was very bold, amazingly so in 1946 and ’47, then he backed away out of fear it would cost him the election in ‘48. Really what Humphrey’s triumph with the civil rights plank at the ‘48 convention did is it forced Truman to run as a civil rights candidate, which ended up being the reason he won the race.

He really starts it in July, Truman, by desegregating the military and the federal workforce, and he culminates it the last weekend before Election Day, having a rally and giving a campaign speech in Harlem, which no major party presidential candidate had ever done.

So I think part of the lesson of what Truman did, for Biden, is to try to be bold, to be assertive, to take some of the risks that need to be taken.

Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

Mayor of Minneapolis Hubert H. Humphrey addressing the Democratic National Convention. Humphrey submitted a minority report urging the adoption of the civil rights plank in the Democratic platform. When the convention adopted the plank, part of the delegation from Alabama and all 22 of Mississippi’s delegates walked out of the convention in protest of the adoption of the plank.

WOLF: Today, we look at Hubert Humphrey as an also-ran of American politics. What were you trying to accomplish writing a book that leads up to this single speech at the ’48 convention?

FREEDMAN: I wanted to fill two gaps. I wanted to, first of all, fill a biographical gap about Humphrey, because if people know him at all today, it’s from a largely disparaged and ridiculed latter part of his career supporting the Vietnam War as Lyndon Johnson’s vice president, getting the presidential nomination in 1968 amid the police riot in Chicago, and then really fecklessly, almost pathetically, running as the establishment candidate against George McGovern for the Democratic nomination in 1972.

And yet, there was this amazing chapter in his earlier life when he had been out there in a way few White Americans of the time were, really putting his entire career at risk to fight the fight for civil rights.

People who felt betrayed by Humphrey in the ’60s because he was no longer being a liberal hero forgot why they thought he was a liberal hero in the first place. And what he did in the 1948 convention is the epitome of it, to get the Democratic Party to endorse the civil rights agenda for the first time ever, and to accomplish something that FDR hadn’t been willing to do, which was to defy and ultimately oust the Southern segregationist wing of the party.

The other gap I wanted to fill was a historical gap, because a lot of the great writing that’s been done about the Civil Rights Movement tends to position its origins in the 1950s with the Montgomery bus boycott and Brown v. Board of Ed decision, and so forth. And yet, there was all this activity in the ’40s, very much catalyzed by Black GIs and the Double V movement (victory in the war and victory over oppression at home).

You know, very much affected by the global war against fascism, and that activity really anticipates and makes possible everything that happens in the ’50s and ‘60s, and yet has gotten much less attention, comparatively speaking. So those were the two gaps I was aiming to address.

WOLF: Humphrey is certainly more associated with that ’68 convention. This year, there’s obviously a fractured Democratic Party, as there was in 1968, and the convention is again in Chicago. What are the similarities you see between this year and ‘68?

FREEDMAN: There are a couple of takeaways from Humphrey’s campaign in ’68. One is you’ve got to really hit the right tone.

The speech that he made in April of 1968 to announce his campaign was so tone-deaf. It talked about the politics of happiness, the politics of joy, and it was completely out of tune with the tenor of the times.

This is like three and a half weeks after Martin Luther King had been killed. It’s just about as long as after Lyndon Johnson decided not to run. There was a massive anti-war movement. It just felt like Humphrey, who usually had such a keen sense of retail politics, totally misread the mood of the country.

He struggled, really for the rest of the campaign, to come back to finding a way to stick to things he wanted to stick to about hope and unity and possibility, while trying to find the words, and I think never really quite succeeding, to acknowledge the hurt, the anxiety, the division within the country.

It’s also a lesson about the importance of optics, and this is even before the 24-hour news cycle. Humphrey is giving his speech at the ’68 convention, where in the middle of his speech, the live TV coverage cuts away to show the Chicago police beating demonstrators and journalists on the streets of Chicago. It’s the most catastrophic optic you could imagine.

Another similarity is that although Joe Biden has run essentially unopposed in primaries, it’s almost as if he didn’t really have to face the Democratic voting public this year, the way he definitely did in 2020, and comes in as feeling more coordinated and less chosen.

In 1968, the Democratic Party was operating under old rules in which primary voters actually had relatively little direct effect on delegates. Humphrey enters late, after Bobby Kennedy had been in, after Eugene McCarthy had been in, and won most of his delegates by going through the party apparatus. So it looked like he had this nomination kind of handed to him by the machine, over and against the passions of the voters, who had turned out in large numbers for Bobby Kennedy and Eugene McCarthy.

That also presents a problem of how do you build up the requisite passion?

At the end of the day, he did something in late September that almost saved his campaign, which was finally to break away from Lyndon Johnson on Vietnam and to stake out a much bolder peace plank on Vietnam. In fact, it was a peace plank that was defeated at the convention where Humphrey’s forces opposed it. Had Humphrey done that sooner would he have won? Good question.

The other important thing Humphrey said, that I think Biden really has to find a way to express, came from the speech accepting the nomination. I’m going to read you this paragraph, because I think it’s so prescient. He says:

I say to those who’ve differed with their neighbor or with those who’ve differed with their fellow Democrat, may I say to you that all of your goals, all of your high hopes, all of your dreams, all them will come to naught if we lose this election, and many of them can be realized with the victory that can come to us.

That is so exactly right, and it’s something that Joe Biden has to communicate.

Just like for people, particularly young liberals, who couldn’t bring themselves to vote for Humphrey in ’68, what they got was Nixon. What they got was, instead of peace talks and a bombing halt, and an internationally supervised ceasefire, which was Humphrey’s stance by the end of the campaign, they got the war going on for seven more years, with tens of thousands more American deaths and hundreds of thousands, if not millions, more Vietnamese deaths.

They got Watergate.

They got the race-baiting that Nixon engaged in. They got the proto-Trump pseudo populism of Spiro Agnew as vice president.

So there’s a real price to pay there for hanging on to your purity of not being able to vote for Hubert Humphrey and forgive him even the egregious mistake on Vietnam because of everything else he brought to the table that was absolutely consistent with the liberal agenda.

Correcting the counterfactual about Republicans and civil rights

WOLF: As I was reading the climax of this book, there was an interview on CNN with Rep. Byron Donalds, the Republican from Florida, who was arguing this counterfactual – and you can find many other instances of it – that a lot of present-day Republicans are pushing that they deserve credit for the Civil Rights Movement, because Abraham Lincoln was a Republican, because there were Southern Democrats who opposed the Civil Rights Act. This comes up in your descriptions of the ’48 convention, particularly with Strom Thurmond (the South Carolina Democrat turned Republican). I was hoping to get your historical analysis of that idea.

FREEDMAN: It’s preposterous for the Republicans to make that argument in 2024 or at any time in the last 60 years, to be honest.

When Strom Thurmond and the Dixiecrats bolted from the Democratic Party in 1948, that’s the beginning of the vast majority of the White South becoming Republicans, stepping away from the Democratic Party.

Even though (Adlai) Stevenson in ’52 and ‘56 and JFK in 1960 tried to lure them back in, it was still the beginning of a process by which – with Barry Goldwater in ’64, who opposed civil rights legislation; Nixon’s “Southern strategy” in ‘68 and ‘72; (Ronald) Reagan’s appeals to racial resentment in ‘80 and ‘84; the Willie Horton ad in ‘88; and then to Trump in all of his races – that all began in ‘48. Those people who walked out with Strom Thurmond and the voters who voted for them never really went back to the Democratic Party again.

While the party labels have remained the same – there is still the Democratic Party and there is still the Republican Party – the people who are voting have totally exchanged places, because the parties exchanged places on the issue of civil rights.

It’s true that, going back to Lincoln, the Republicans were seen as the party of emancipation and the amendments that created, at least on paper, racial equality.

On that basis, until 1948 really with Truman, and then in even larger numbers in 1964 with LBJ and consistently since then, the White Southern vote that used to go to the Democrats, because the Democrats were the party of Jim Crow, has become the solid White vote for the Republican Party.

Show me a major Republican politician in the MAGA movement who is a fervent supporter of civil rights legislation.

In any kind of iteration, you don’t have (Republicans) now like Mitt Romney’s father, (former Michigan Gov.) George Romney, or (former Pennsylvania Gov.) William Scranton, or Edward Brooke, a Black senator from Massachusetts … You don’t even have people like Nixon, before he went bad on civil rights, who was a really active member of the NAACP.

That doesn’t exist in the Republican Party anymore, and it’s just absurd to say that because 80 years ago to 100, 120 years ago, the Democrats were indeed the party of segregation, that that’s somehow still the case.