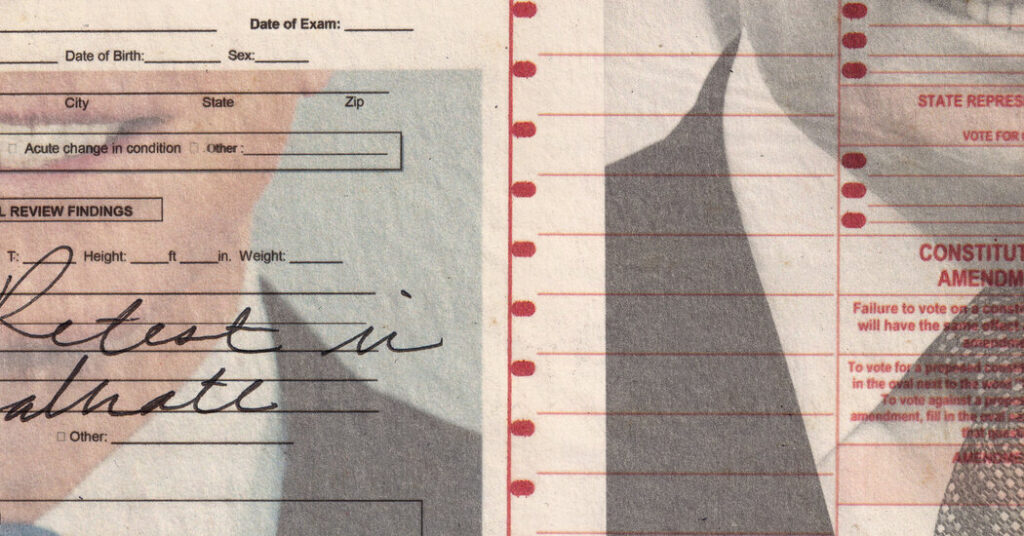

One of the most troubling issues surrounding this election is the health of the elderly candidates themselves.

Biden is 81, while former President Donald Trump is 78. This is the first time a major party has nominated such an elderly candidate for the presidency. Both men are believed to be showing signs of cognitive decline, sparking calls for greater disclosure about the health of presidential candidates.

These arguments raise tough questions that won't feature in this week's debate, but which are nevertheless increasingly timely: How much information should politicians provide to the public about their health? And more broadly, who decides how old is too old as society ages? It's natural to assume that doctors would know more about the health of Trump or Biden than other voters. But it's not that simple.

Politicians' health has long been the epitome of secrecy and political maneuvering (think President Franklin Roosevelt, who was rarely photographed in a wheelchair). But it's more pressing today, as social media amplifies questions about the health of public officials, like the health of Pennsylvania Senator John Fetterman, who became the subject of much debate when he ran for office while recovering from a near-fatal stroke, or former President Trump's COVID-19 diagnosis while in office and the highly politically charged speculation about its severity.

This isn't surprising: So much of politics is about perceptions, and health is intertwined with perceptions of strength. And for good reason: The public should know if a presidential candidate is likely to die in office. Some of it also stems from the stigma that comes with illness and old age: we've long confused illness and disability with weakness.

It is time to question these assumptions. More people are living with diseases that were once fatal. Cancers that were once incurable are now chronic. Diseases such as heart disease are manageable. These changing realities must be taken into account when considering the health of political candidates. It is also important to analyze the difference between disabilities that require accommodation but do not prevent one from performing one's job (for example, blindness or wheelchair use) and disabilities that are progressive and potentially life-threatening. Ageing can lead to life-threatening diseases, but aging is a process that we all go through.

But it is nearly impossible to carefully assess the health of political candidates when health information itself is politicized and the truth is unclear. For example, Trump enthusiastically spoke about doing well on the 2018 Montreal Cognitive Assessment and recently said Biden should also take the test. But what is not clear in Trump's remarks is that this is a screening test for dementia and other cognitive decline, not an aptitude test. Any presidential candidate would be expected to do well, but it is not something to announce. While candidates may be happy to report the results of physical exams performed by their own physicians, it may be more useful to receive objective data such as laboratory test results or, if cognition is an issue, more extensive neuropsychiatric testing. If we are to require politicians to disclose their health information, we need to receive that information in a standardized way; it is not something one party can use as a weapon against the other.

Health information about age is particularly complicated because there is no test that can tell you how old you are. Too Age increases with age, and in many fields where individuals have a great deal of power, no formal age limits or tests are required to assess the impact of age. For example, there are no formal age limits for performing surgery, and no mandatory cognitive or physical tests. Surgeons and their colleagues have a responsibility to discipline themselves and know when the balance is tipping and it is time to step back.

This is a tough decision that inevitably involves how we come to terms with death and how we define ourselves. I've heard from colleagues that some surgeons have come to this decision after not one but multiple poor patient outcomes or close calls. But it's a decision that each of us must make, in our own way, at some point, if we're lucky enough to reach old age. There are countless other examples, like deciding when to stop driving or when to stop living alone.

Whatever that cutoff is, it varies from person to person and changes over time. When I started working as a physician, there was an official age limit that made patients with organ failure ineligible for transplants. Even if you were 75 and healthy, if you had severe lung disease, you were simply too old to receive a transplant. That donated organ would be useful for a younger person.

But now many transplant programs have no such hard cutoffs. Instead, they look to broader markers of health and resilience, such as frailty, to provide an indication of whether marginal patients once thought of as unacceptable age would benefit from a transplant. This makes sense. But if we keep pushing the upper limit, there will inevitably come a time when we go too far, for example by performing transplants on people who are too frail to benefit. Or by allowing surgeons into the operating room despite obvious physical or cognitive deficiencies. Or even by pushing the age limit when it comes to elected officials. Of course, all of these examples are different, but they come from the same changed perception of age.

It's easy to say that 40 is the new 30, 50 is the new 40, etc. What that actually means varies from person to person. For some, it might mean living decades between retirement and death, while for others, it might mean never being able to retire in the first place.

Age is a reality — someone in their 80s isn’t incompetent to be president — but because presidential candidates aren’t required to release their health records, the public remains uncertain about how aging will affect candidates.

this is, all Medical data should be made public, but we would benefit from consistent and proper medical data across candidates, so we would understand that age is not a political weapon, but just another factor we must consider along with political views and experience.

Since taking office, there have been many examples of hidden illnesses, secrecy and stigma around illness. But illness and aging do not have to be synonymous with weakness, and they do not have to be hidden from public view. Intensive care units need to know the age and comorbidities of their patients so they know how to treat them most effectively, what they can tolerate, and when to back off.

As Americans, we are entitled to this same level of understanding about the health status of our political candidates.

Daniella J. Lamas is an opinion writer and pulmonologist and critical care physician at Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston.

The Times is committed to publishing Diverse characters To the Editor: Tell us what you think about this article or any other article. Tips. And here is our email: letters@nytimes.com.

Follow The New York Times Opinion section Facebook, Instagram, Tick tock, WhatsApp, X and thread.