CNN

—

Iran's second presidential election will head to the polls on Friday, pitting reformers and hardline conservatives against each other to succeed Ebrahim Raisi amid unprecedented voter apathy.

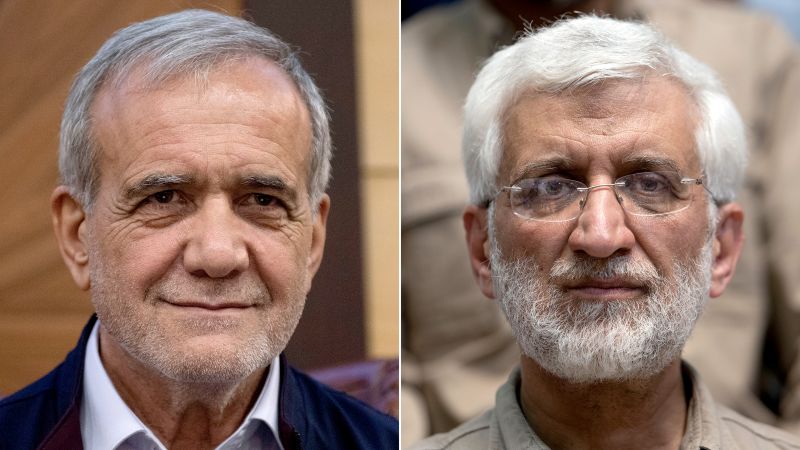

None of the original four candidates received more than 50 percent of the vote in the June 28 election, but reformist lawmaker Massoud Pezeshkian and ultra-conservative former nuclear negotiator Saeed Jalili were the two most popular candidates, with Pezeshkian leading by 3.9 percentage points.

But the first round saw the lowest turnout for a presidential election since the Islamic Republic was established in 1979, highlighting discontent among a population that has lost faith in the country's ruling clerical establishment.

Pezeshkian and Jalili are at opposite ends of the Iranian political spectrum and could have very different ways of leading a country at a time when it is grappling with sensitive domestic and international issues, including a collapsing economy, a destabilizing youth movement and rising tensions with Israel and the United States.

Here's what to expect from Friday's second round of elections, and how the outcome could affect Iran and the world.

The elections were held after Raisi was killed in a helicopter crash on May 19 in the country's northwestern frontier, along with Foreign Minister Hossein Amir Abdullahian and other senior government officials.

Three conservative and one reformist candidates competed for the country's top electoral seat after dozens of other candidates were barred from running by the powerful 12-member Guardian Council, which oversees elections and legislation and reports directly to Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

Pezeshkian came out on top in the first round with 42.5% of the vote, followed by Jalili with 38.6%, according to the state-run Iran News Agency. Of the 60 million eligible voters, 24 million cast ballots, giving a turnout of 40%.

In a country where voter turnout in presidential elections typically exceeds 60 percent, turnout was a record low despite Khamenei calling on Iranians to show “maximum participation” to strengthen the Islamic Republic against hostile forces.

Iranians speaking to CNN in Tehran ahead of the first vote expressed little trust in the candidates running, especially since they are being vetted by the Guardian Council.

The turnout suggests that “this anger and disillusionment with the entire regime is not limited to reformists,” Trita Parsi, a Washington-based Iran analyst and vice president of the Quincy Institute, told CNN. “There seems to be a lot of anger and disillusionment with the regime among conservatives as well, because their turnout was also very low.”

Still, analysts say a significant shift may be taking place among voters ahead of the second round, with some voters, including conservatives who supported hardline candidate Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf in the first round, appearing to support reformist Pezeshkian at the expense of his conservative rival, Djalili.

“There is clearly a split among the conservatives,” Parsi told CNN, including within the elite Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), the group in which Jalili previously served.

Analysts have suggested that some conservatives believe there is a need to shift away from some of the uncompromising policies of the late President Raisi, which Jalili will likely continue.

One such conservative is Sardar Mohsen Rashid, a founder and senior member of the IRGC, who on Monday voiced his support for Pezeshkian and called on people to protect him from “despicable attacks,” according to the Iranian conservative news site Khabar Online.

In a move that shocked observers, Sami Nazari Tarkarani, who led Ghalibaf's election campaign, also voiced his support for the reformist Pezeshkian, Khabar Online reported.

It's unclear whether the change will be reflected on the ground, but other supporters of Ghalibaf said they are also reaching out to conservative and silent voters to back reformist candidates.

Analysts also say the division among conservatives shows that sentiment within the camp is not uniform.

“Anti-regime sentiment is not limited to reformists, it also exists within the IRGC,” Parsi said, adding that the current rifts are particularly pronounced given the regime's efforts to concentrate power in the hands of conservatives alone.

Sanam Vakil, director of the Middle East and North Africa program at the London think tank Chatham House, added that Iranian politics are divided into factions and “not everyone in the IRGC supports or prefers conservative or hardline politics.”

Experts say both candidates seemed intent on garnering votes from the 60 percent of voters who didn't attend Monday's presidential debate.

“Pezezhkian has adopted more extreme rhetoric in an effort to attract non-voters,” Sina Toussi, an Iran analyst and senior fellow at the Center for International Policy in Washington, D.C., wrote on X. “Meanwhile, Jalili has sought to soften his own image and has repeatedly agreed with Pezeshkian.”

Pezeshkian, who comes from an Azerbaijani Kurdish family, has sought to appeal to ethnic minorities, women and the country's youth, Toosi wrote.

Majid Asgaripour/WANA/Reuters

On a street in Tehran, Iran, on Monday, people drove past a billboard featuring photos of presidential candidates Masoud Pezeshkian and Saeed Jalili.

During Monday's debate, the candidates said the administration “appoints people from its own camp and excludes the rest of the people.”

Pezeshkian famously criticized the regime's response to the mass protests in 2022 in an interview with Iran's IRINN TV, saying, “This is our responsibility. We are trying to enforce our religious beliefs through the use of force. This is scientifically impossible.”

“The problem of the poor is us,” he said during the debate, referring to poverty in Iran, adding that if candidates want to increase voter turnout, “voters have to believe that officials are sitting at the same table as them.”

Millions of people in Iran live below the poverty line and struggle to make ends meet in an economy battered for years by U.S. sanctions. Iran's annual inflation rate has not dipped below 30 percent for more than five years and hit 36.1 percent in June, straining wallets across the country.

This persistent inflation comes after the Trump administration withdrew from the 2015 nuclear deal and subsequently reimposed harsh sanctions on the Islamic Republic.

Pezeshkian stressed the need to resume dialogue with Western countries and find a way to end the sanctions.

Relations between Iran and the West have only deteriorated in recent months, with Iran backing militant groups across the Middle East that target Israeli and US interests amid the war in Gaza. Iran has also escalated its nuclear program and rolled back cooperation with the International Atomic Energy Agency, the UN nuclear watchdog.

During the presidential debate, Jalili also appealed to women and young people, saying “the voices of students and Iranian youth must be heard.”

But he maintains his position that Iran should not rely on the West to ensure progress, a view echoed by the supreme leader in recent weeks.

“We must make our enemies regret imposing sanctions on us,” Jalili said, adding that the Western threat must be turned into an opportunity, echoing the late President Raisi's efforts to forge friendships with America's enemies as the West became isolated.

The candidates' opposing views emerge amid an intensifying dispute between Iran and Israel. The two countries exchanged direct attacks for the first time in April as the Gaza conflict escalated, and Israel is now preparing for a potential second front with Hezbollah, Iran's main regional proxy in Lebanon.

Iran's UN mission said on Saturday that if Israel “launches a full-scale military invasion” of Lebanon, “a devastating war would occur.”

“All options are on the table, including the full involvement of all resistance fronts,” X reported.

Israeli Foreign Minister Katz responded on Saturday, saying “a regime that threatens to be destroyed deserves to be destroyed.”

How much autonomy will either candidate actually have?

Rising regional tensions have raised questions about whether a reformist president can really bring about change, and experts say his chances may not be as great as some in the West hope.

The supreme leader has the final say on most decisions in Iran, but “that doesn't mean the president and his foreign policy team are irrelevant,” said Ali Vaez, Iran project director for the International Crisis Group.

The president and his Cabinet implement foreign policy and have great influence over the country's diplomatic apparatus, Vaez said in an interview with CNN's Becky Anderson on Monday.

Morteza Fakhri Nezhad/IRIB/WANA/Reuters

Presidential candidates Masoud Pezeshkian and Saeed Jalili attended an election debate at a television studio in Tehran, Iran, on Tuesday.

He noted that the reformist President Pezechkian is surrounded by “the cream of the Iranian diplomacy” and that his presidency will be very different from Jalili's.

But Iran's track record so far shows it tends to take a more conservative trajectory in the long term, even when a reformist president takes office, the experts said, adding that Iran's regional policy towards Israel and its proxies is unlikely to change.

Parsi said a reformist president was unlikely to bring about changes when it came to core Iranian policies such as support for Hezbollah and hostility toward Israel, but added that better engagement with the West was possible.

Nonetheless, Jalili is likely to bring tougher policies to the table and double down on his predecessor's approach.

Depending on the Western environment, Jalili “may take a more confrontational approach towards Iran's nuclear program,” Vakil said, adding that despite the president's limited freedom of action, each brings “his own personality” to the Iranian government.