As voters go out to choose Iran's new president, Euronews takes a look at the two candidates facing off on Friday and the main concerns of voters.

Iranian voters are about to decide who will be the number one in the country's executive branch in a second round of elections.

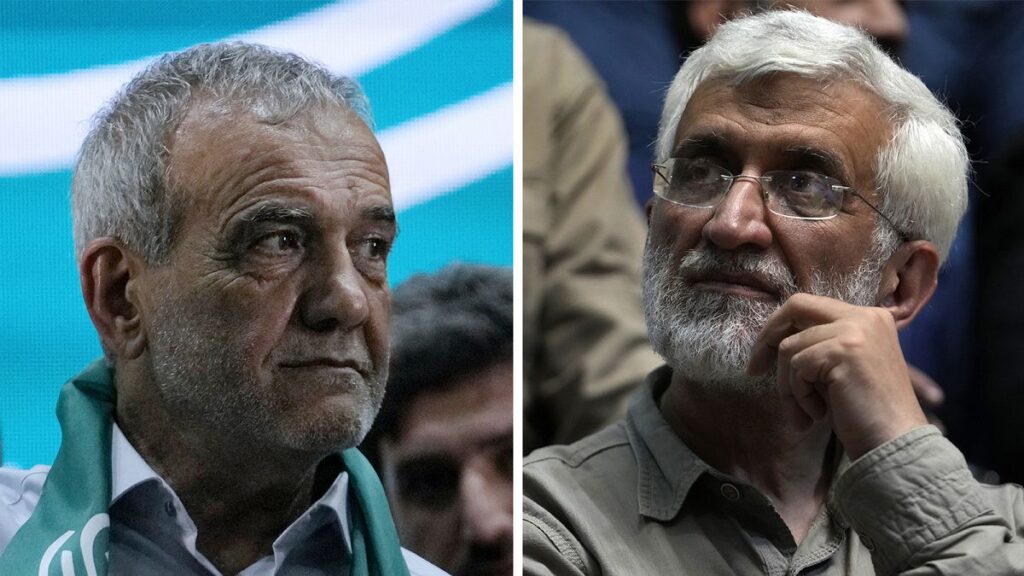

They will choose a new president to replace the late President Ebrahim Raisi, who died in a helicopter crash in May, from a pool of candidates close to two rival political factions: little-known reformer Massoud Pezeshkian and hardline former nuclear negotiator Saeed Jalili.

As the runoff election will determine the future direction of the country, the main topic of conversation has been low turnout in the first round and speculation about voters' ultimate choice.

But who are the two candidates facing off on Friday, and what are voters' main concerns?

Pezechkian vs. Jalili: Key issues

During the election campaign, Pezeshkian aligned himself with other moderate and reformist figures.

His main supporter is former Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif, who secured the Iran nuclear deal with world nations in 2015 that lifted sanctions in exchange for significantly curtailing its nuclear program.

Pezeshkian, a cardiac surgeon, said in a televised debate on Tuesday that Western-imposed sanctions have severely hurt Iran's economy, citing a 40 percent inflation rate over the past four years and rising poverty rates.

“We live in a society where many people are on the streets begging,” he said, adding that his administration would “immediately” work to lift sanctions and vowed to “fix” the economy.

Jalili, Pezeshkian's hardline rival, is a vocal opponent of the 2015 nuclear deal and said at Tuesday's debate that the United States must honor its commitments “as much as we have.” He criticized his opponent for not having a plan to lift sanctions and said he would restart talks on the nuclear deal.

Known as a “living martyr” after losing a leg in the Iran-Iraq war of the 1980s and known among Western diplomats for his preachy speeches and tough stance, Jalili also promised to support Iran's stock exchange by insuring shares and providing financial support to local industries.

He is running for president for the fourth time.

Who will the Ayatollah prefer?

Some political analysts believe that Pezechkian was the regime's main candidate in the elections from the start, as Tehran hopes to resolve part of the crisis by installing a moderate reformist president.

But political analyst Abbas Abdi, who was one of the closest aides to another reformist in the elections, Massoud Pejikian, told Euronews that the administration did not consider Abdi its absolute favourite and had to make peace with Pejikian as president during the election period.

“I think they welcomed the election of Pezeshkian because there have been failures and policy changes in Iran with the policy of unity. But saying they chose Pezeshkian as their candidate means they desperately wanted him to become president. That's not the case,” he explained.

Meanwhile, journalist Mohsen Sazegara, a prominent opposition leader abroad, is convinced that Jalili was the choice from the start by Ayatollah Ali Khamenei's son Mojtaba, who is said to be the next in line to succeed him as Iran's supreme leader.

“Mojtaba Khamenei has promoted Saeed Jalili, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) intelligence wing is behind him and has even selected ministers in his government,” Sazegara told Euronews.

But Sazegara explained that Khamenei may not yet be fully convinced and may need time to open up to Jalili. “Jalili's presidency is Mojtaba Khamenei's wish, but the keys are in his father's hands.”

What does the low voter turnout say about Tehran's problems?

But both candidates may suffer from low voter turnout: In the first round, only 39.9% of eligible voters cast ballots, and about 4% of ballots were later invalidated, meaning hundreds of thousands of people had their ballots invalidated only to say they voted.

Iranians remain angered by years of poverty, a stagnant economy and a harsh crackdown on anything perceived as even the slightest bit of dissent, including mass protests over Mahsa Amini, who died in 2022 while in morality police custody.

Tensions with the United States and Western countries over enriched uranium and the ongoing war between Israel and Hamas in the neighbouring region – which could spill into open conflict with Lebanon's Hezbollah – have divided voters over who will take the helm if things escalate further.

But for some, the reason not to vote hinges on the fact that the Iranian president has limited power: he is the second most powerful person in all decision-making after the ayatollah and can on paper choose his own cabinet, though he usually doesn't even do that.

Simply put, in Iran, the president's main role is often to cater to the whims of the ayatollahs and the Revolutionary Guards, Sazegara said.

“Many people say there is no difference between electing Pezeshkian and Jalili, which means our problems will not be solved in this election,” he said.

Rather, voters want to choose candidates who can game the system in ways that will make their lives a little better, without making them worse off.

“In my opinion, this mock election was not and is not actually a choice between Jalili and Pezeshkian or any other candidate. The ballot box placed before the people is actually a choice between the will of the people and Khamenei, the leader and dictator of Iran.”

“Khamenei has always stressed that the people's vote in any election is a vote for the regime, and by regime he means himself,” Sazegara concluded.

Meanwhile, Abdi believes it's still important to go vote.

“The reality is, (we're talking about) the future. We can't say for sure which decisions were right and which were wrong,” he told Euronews.

“If some people don't vote and Jalili becomes president, they might later regret not having done something to help Pezeshkian become president. So in that sense, it's hard to say which decision was the right one.”

Can Pezeshkian really bring about reform in Iran?

Pezeshkian, who was the leading favorite to win after the first round, is seen by some as the person who can lead Iran out of its ongoing economic crisis, end the oppression of women and promote online freedom in the country.

But neither Abdi nor Sazegara are optimistic that this will be the case.

“These are very important and serious issues for Iran. Of course, Pezechkian's government will definitely improve internet freedom. There will be less pressure on women,” Abdi said. “But I don't see these issues being resolved anytime soon.”

Sazegara offered an even more dire estimate.

“In my opinion, within the framework of the Islamic Republic's existing institutions and flawed and corrupt structures, even Otto von Bismarck could not have improved Iran's economic situation,” he said.

“So unless the system changes, unless the government's macro policies change, unless the concentration of power and wealth is removed from the hands of the powerful, there is no hope of reform in any area.”

Sazegara believes Pezeshkian knows this and that his election promises could backfire and make Iranians even more disillusioned with their leaders.

“Anyone who promises reforms knows it is futile, but in reality a promise to the people is a promise to the people,” Sazegara concluded.