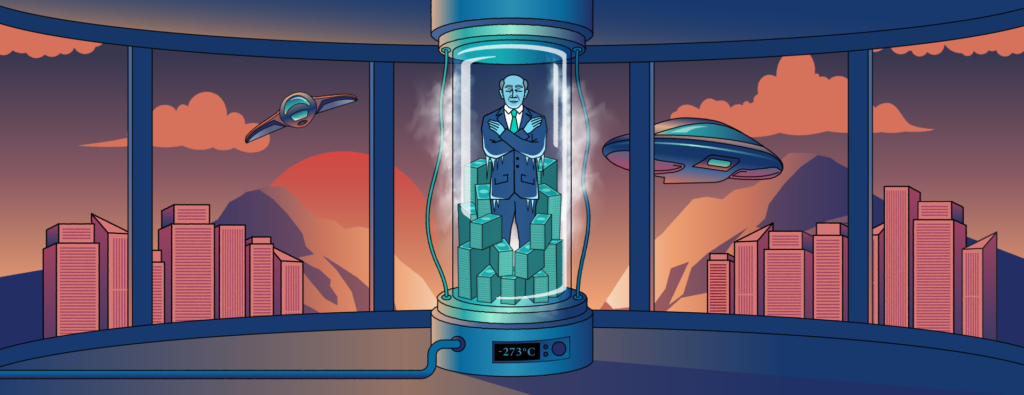

Nobody wants to come back from the dead poor.

Fortunately for the wealthy, immortality of wealth is a easier solution than reversing death.

Estate lawyers are setting up trusts designed to extend the assets of cryopreserved people until they are resurrected, even if that may be hundreds of years later. These resurrection trusts are a new area of law built on many assumptions. But they are being taken seriously, attracting true believers and worthy of discussion at industry conferences.

“The idea of cryonics has gone from being outlandish to just plain weird,” said Mark House, an estate attorney with the Scottsdale, Arizona-based Alcor Life Extension Foundation, the world's largest cryonics center, with 1,400 members and about 230 people frozen. “Now that it's weird, it's kind of fashionable to be interested in cryonics.”

By one estimate, about 5,500 people are planning to be cryopreserved, and House estimates he has worked with about 100 of them.

He and others are trying to answer questions that sometimes seem like questions posed in a philosophy class.

Can money last forever?

Will a body die if it is frozen?

Would just the brain be considered resurrected?

And when you come back to life, will you be the same person?

How to save money

For Steve Rubel, a retired Michigan hospital executive, the chance to join about 500 others already frozen out felt like a dream come true.

The 76-year-old Rubell is always looking for new ways to spend his time — most recently as a young adult fantasy writer — but he loves life and doesn't want to let money get in the way of a second chance.

Rubel said he has been searching for about a year for a trust model that would likely endure for centuries.

He plans to donate $100,000 to a recovery trust and the rest to his daughter and her husband, as well as his own foundation.

“I really want to find a solution, otherwise I guess we'll just be crossing our fingers and praying that in 200 years there's money left to pay for the revival,” Rubel said.

What is the real “you”?

The Revival Trust is a variation of the Dynasty Trust, a vehicle used by the ultra-wealthy who plan to pass their wealth down through generations.

Both can help avoid the 40% federal tax on estates over $13.6 million, but investment gains are subject to income tax and trustees charge potentially hefty fees. (House requires clients to put at least $500,000 into the trust to ensure funds aren't depleted by fees.)

The difference is the beneficiaries.

House believes that resurrected persons are a separate entity in law, in part because they can't be beneficiaries of their own trusts. When he sets up trusts for his clients, the only beneficiary is the resurrected person.

House said trying to overturn a death certificate would create legal confusion. He gave the trust protector, a person or entity that can change trust agreements, the power to determine whether resuscitation has occurred.

To Florida-based estate planner Peggy Hoyt, the resurrected figure is the same person.

She says a trust needs to have an active beneficiary, so she often stipulates that her client's family or a cryonics facility receive the money while they are frozen. Including a cryonics facility or charity ensures that the trust has a beneficiary, even if the client's heirs die. She also asks her clients to explain their personal definition of reanimation.

“Some people would only consider resurrection if they were the same person they are now, with all their memories intact,” Hoyt said. “Others are content to say that cloning is the equivalent of resurrection. Others say they don't mind having a body as long as their brain is uploaded to a computer.”

Perpetual Trust

Resurrection trusts also push the boundaries of the law for perpetual trusts, which are intended to prevent the wealthy from accumulating funds for generations.

Most state laws limit the life of a trust to 90 to 100 years, but some states have eliminated or extended perpetual inheritance protections to combat investment income tax evasion from trusts, said George Bearup, senior legal trust counsel at Greenleaf Trust.

In Arizona, where House lives, trusts can last up to 500 years. In Florida, the limit is 1,000 years.

“It got people thinking, 'If I had a 1,000-year trust, what would I want to do?'” Bearup said. “I think that's what prompted people to think about preserving their bodies.”

What could be the problem?

Like any prospect of a revival, a trust structure is a leap of faith that could fail if policies or business change, which is one reason Bear Up hasn't tried such an arrangement.

“I'd probably run the other way,” he said. “How do you draft for something that might happen 1,000 years from now? Who knows what the rules will be?”

Cryopreservation estate planners are grappling with the potential impact of a February ruling by the Alabama Supreme Court that said frozen embryos are considered children and therefore subject to the state's wrongful death law.

The arrangements would have to take into account the advent of technologies and medical procedures that have not yet been invented. The federal government would probably ban perpetual trusts. Trusts are usually administered by trust companies or banks, but no one knows whether the trustee will still be there when the person is resuscitated.

This makes flexibility and succession planning important for trust administrators and trust protectors.

“When you start thinking in centuries-long time frames, nothing can remain static,” House said.

Rubell doesn't want to take the risk of using a bank or trust company as a trustee, and he's working with the board of directors of the Michigan-based Cryonics Institute to have the facility also act as a trust company, which he thinks is a more robust model.

House said he worked with Alcor to set up a trust guardianship committee that would appoint new members after a certain number of years. When the original guardian named in each arrangement dies, the committee takes over.

A resurrection trust should spell out what happens if some of the trust's terms fail or if scientists discover years later that it's impossible to bring the dead back to life through a frozen head, said Victoria Hanneman, a professor of trusts and estates at Creighton University who has studied the tax implications of resurrection trusts.

If restructuring isn't possible, the court would review the trust, and the terms of the trust should include what should happen to the funds in that case, such as naming the charities that would receive them, Hanneman said.

But who decides that revival is impossible?

Rich, Immortal

Still, the fascination with immortality and what it means is undeniable.

As science advances, more and more people are considering cryonics as the last great experiment, and tech moguls Jeff Bezos, Sam Altman, Larry Ellison and Larry Page have pledged hundreds of millions of dollars to companies trying to defy death and aging.

Earlier this month, Cradle Healthcare, a company led by biotech whiz and longtime investor Laura Deming, entered the cryonics business with $48 million in funding and the promise of developing the rewarming technology that's key to resuscitation. The move brought some much-needed credibility to the industry.

“I believe we can cure aging,” LeBel says, “Aging is a disease. We're not there yet, but cryopreservation can bridge the gap.”