This section offers an analysis of political language, drawing on a wide range of scholarly literature. It begins with a theoretical examination of the symbolism and nuances present in political discourse, with a particular focus on the rhetorical strategies employed by presidents. Wittgenstein (1973) accentuates the indispensability of attaining proficiency in language comprehension within specialized contexts, underlining the multi-dimensional intersections and adherence to societal norms, governing principles, and prevailing paradigms unique to diverse societal constructs. Such a profound analysis is crucial to unravel the multifarious intertwining of language, symbolism, and politics. It constructs a solid structure that enables a detailed examination of political rhetoric, leading to a deeper grasp of the various nuances and subtleties inherent in political language. This improved understanding sheds light on the interplay within this complex field, illustrating how different components interact and coalesce to shape the political environment.

Drawing on the foundational theories of Wittgenstein (1973), and enriched by the analytical insights of Bourdieu (1991) and Foucault (1972), the research underscores the critical importance of contextual linguistic proficiency. It reveals the relationships and alignments between social norms, legal frameworks, and the prevailing cultural patterns of diverse communities (Fairclough, 1989; Lakoff, 2004). This analytical process is vital for unraveling the complex interplay between language, symbolism, and political structures. Therefore, the study offers a framework that enables a deeper and more detailed exploration of political rhetoric, influenced by the influential contributions of Charland (1987) and McGee (1980).

The examination extends into the crucial role of symbolism in political dialogs, especially within the rhetoric of presidents. It becomes an integral element in delineating the structures of political ecosystems. Insights from this exploration draw significantly from the fundamental concepts introduced by Edelman (1964, 1971, 1988), who expands upon Wittgenstein’s groundbreaking ideas, illuminating the web interlinking politics, symbolisms, and various linguistic elements. Edelman (1988) suggests that political language transcends mere representational functionalities, acting as an influential architect of societal realities and enabling politicians to forge and reinforce support for their diverse ideological perspectives.

An exploration of the multifaceted dimensions of symbolism in political dialogs unveils a realm marked by dynamism and complexity. Distinct scholars, including, Campbell and Jamieson (1990), Hart (1987), Stuckey (1989), and Zarefsky (2004), with insights from Burke (1969), Ceaser et al. (1981), and Fisher (1984), probe into the layered facets of presidential rhetoric. They reveal how symbolic language encompasses and conveys the profound complexities of political ideologies, molding national narratives and influencing public perceptions and interpretations of varied political philosophies.

In the current epoch, characterized by profound political polarization, the significance of symbolic rhetoric in shaping public discourse is increasingly evident. This form of rhetoric acts as a potent catalyst, with the capacity to either exacerbate or mitigate the stark ideological divides prevalent in society (Iyengar and Hahn, 2009; Stuckey, 2021. The complex and varied nature of symbolic expressions in political communication demands a thorough and nuanced examination. Such an analysis is crucial for understanding the diverse ways in which these expressions influence and shape public opinion and ideological leanings within various political contexts (Habermas, 1984; Entman, 2003).

This heightened role of symbolic rhetoric in the contemporary political landscape can be attributed to its ability to encapsulate and convey complex ideological positions in a manner that is both accessible and emotionally resonant. Symbolic rhetoric, by its very nature, simplifies and distills political ideologies into potent symbols and narratives that resonate with individuals’ pre-existing beliefs and values. This process not only reinforces existing ideological divides but also has the potential to bridge them, depending on the nature and context of its use.

Furthermore, the study of symbolic rhetoric in political communication extends beyond mere analysis of language. It encompasses an exploration of the socio-cultural and historical contexts that give rise to specific symbolic meanings. This approach recognizes that symbols are not static; their meanings and implications evolve over time and are shaped by the sociopolitical milieu in which they are used. Therefore, a comprehensive understanding of symbolic rhetoric in politics involves examining the interplay between language, history, and social dynamics.

Acknowledging the paramountcy of symbolism in political dialogs, this study underscores the pivotal role of public communication within political structures. A body of work (Condit, 1987; DeLuca, 1999; Hart, 2002; Ivie, 1987; Kermani, 2022; Lakoff, 2016; Lim, 2002; Stuckey, 1989, 2010, 2021; Zarefsky, 2004) depicts the strategic utilization of rhetorical components by presidents to align public sentiments with their governing ideologies. Such alignment is integral to elucidating governmental philosophies (Eshbaugh-Soha, 2008; Peake and Eshbaugh-Soha, 2008), creating resonances across national and international domains, traversing numerous layers.

The complex interplay between presidential engagement in public rhetoric and the narratives advanced by the media significantly influences and directs public dialog. Presidents, demonstrating keen insight, utilize various strategies to navigate the complex terrain of media coverage (Maltese, 1994; Bennett, 2008). The delivery of presidential speeches becomes a key conduit in the public sphere (Edwards, 2003; Eshbaugh-Soha, 2008), guiding government priorities, media interactions, and public attention, while aligning closely with collective issues (Cohen, 1995; Hart, 1980), thus profoundly impacting national discourse.

Jayu: symbolic embodiment and ideological demarcation in Korean politics

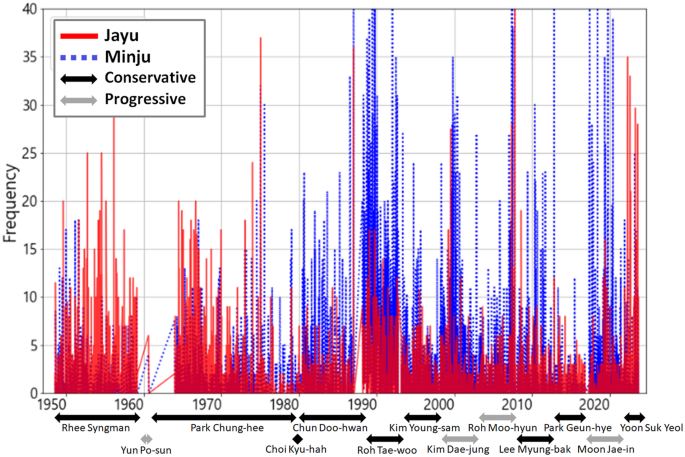

This study employs a comparative approach to scrutinize the strategic use of the term Jayu (freedom or liberty) in Korea’s political discourse, integrating it within the broader context of symbolic rhetoric in political communication. Korea, as a key democratic entity in Asia, provides a unique analytical ground for understanding how political language is imbued with ideological currents. Within this landscape, Jayu predominantly represents a conservative ideology, a notion deeply entrenched in the societal fabric, contrasting with the Democratic factions’ preference for “Minju” (Democracy), rather than “Liberal Democracy.”

The distinction between Jayu and Minju extends beyond simple linguistic differences, revealing a profound ideological divide that is consistently reflected in the discourse of President Yoon Suk Yeol. Yoon’s staunch support for liberal democracy is apparent, particularly during pivotal political junctures. His commitment was notably articulated upon his resignation as Prosecutor General on March 4, 2021, amid escalating tensions with the Moon Jae-in administration, where he declared his unwavering dedication to safeguarding liberal democracy and the citizenry, regardless of his official capacity. Furthermore, during a press conference for the presidential election on June 29, 2021, Yoon vehemently underscored the significance of Jayu, critiquing the Moon administration, “(Moon Jae-in administration) is trying to take the word, Jayu, out of liberal democracy which is the basis of our constitution.” The evolution of political party names further illustrates this distinction. Conservative factions have traditionally used names that include the term Jayu, starting with the ‘Jayu-Dang’ (Liberal Party) in 1951 and later evolving into the ‘Jayu-Hankuk-Dang’ (Liberty Korea Party). Conversely, Democratic factions have consistently aligned with the term Minju, as exemplified by the contemporary ‘Minju-Dang’ (Democratic Party of Korea).Footnote 1

The ideological landscape encompassing liberal democracy and democracy remains a topic of ongoing debate among scholars and politicians. The notable disparity in the frequency of Jayu usage by President Yoon during his inauguration, as opposed to its absence in Moon Jae-in’s rhetoric, highlights the complexity and layered nature of Jayu in Korean political discourse. The term transcends its original conceptual confines, encapsulating ideologies ranging from “outdated anti-communism” to “far-right totalitarianism,” and its omission leads to implications of alignments with “pro-North Korea” and “anti-establishment” stances (Moon, 2019; Yang, 2021).

Exploring the historical evolution of Jayu and Minju, this research contextualizes their use against the backdrop of historical and geopolitical shifts, notably during the Cold War and post-Cold War periods. The strategic employment of Jayu by conservative leaders during these times was aimed at legitimizing and maintaining governance, portraying it as a defense mechanism against communist infiltration, thus rallying public and international support for Korea’s anti-communist stance. The symbolism of Jayu encompasses anti-communist connotations derived from historical contexts, notably the Korean War and the persistent existence of North Korea (Kim, 2014; Kim, 2017). Within this historical and ideological backdrop, conservative factions prioritize individual freedoms, deriving their convictions from the perceived failures of the collectivist communist regime in North Korea.

Throughout the Cold War and into the evolving geopolitical context of the Indo-Pacific region, Korean authoritarian governments strategically utilized anti-communism both as a domestic political tool and as a means of aligning with Western powers. This strategic narrative, particularly emphasized during the Vietnam War and the Cold War, helped consolidate conservative power by fostering a pro-liberty, anti-communist identity (Steinberg and Shin, 2006; Kang, 2008). The frequent invocation of Jayu in political discourse served dual purposes: it functioned as a mechanism to achieve domestic political objectives and as a strategic element in strengthening Korea’s position as a vital ally in the global anti-communist movement (Cumings, 2005; Han, 1980; Moon and Kim, 2002; Shin, 2017). Despite shifts in the diplomatic relationships between Western countries and communist bloc nations during the Cold War, Korea’s authoritarian rulers consistently leveraged strong anti-communist sentiment (Shin, 2017). This sentiment became a central principle that suppressed ideological debates and criticism within domestic politics, even amidst the discreet diplomacy of the West during the Cold War and following the collapse of communist regimes (Choi, 1993). This persistent use of anti-communism illustrates how it was instrumentalized to maintain political power and limit political discourse in Korea.

The prolonged prevalence of military regimes characterized by growth-oriented ideologies suppressed conventional conflicts inherent within capitalist industrialization processes (Im, 2020b; McAllister, 2016; Porteux and Kim, 2023). During this period, Korean politics evolved distinctly, characterized by a dichotomy between authoritarian conservative governance advocating Jayu and civil society’s democratization movements promoting Minju (Im, 2020b; Lee, 2009; McAllister, 2016). This contrast not only epitomized internal political and ideological struggles but also influenced the broader strategic orientations of conservatives and progressives in domestic politics.

In the early 2000s, the Korean New Rights movement emerged as a significant force within the context of conservative disillusionment following repeated electoral losses. This movement marked a shift towards liberal democratic values, advocating for them as superior to the broader concepts of democracy. The shift was partially driven by changes in educational content and public discourse, which mirrored a deep ideological divide between conservative and progressive interpretations of the concept of Jayu (Lee, 2013; Moon, 2019; Yun, 2012; Kang, 2014). This development was not isolated but intertwined with global neoliberal trends, illustrating the intricate interaction between local and global political dynamics.

Although the New Right encompasses a range of viewpoints and should not be viewed as homogeneous, certain characteristics differentiate it from the Old Right. While the Old Right is often characterized by its anti-communist stance, the New Right is distinguished by its pro-market orientation. Additionally, the New Right has introduced revisionist perspectives, including theories of colonial modernization, the founding of the nation in 1948, and reevaluations of Rhee Syngman’s legacy (Lee, 2013; Moon, 2019; Yun, 2012; Kang, 2014). These historiographical perspectives have ignited societal debates, reminiscent of the controversies surrounding national textbooks during the administrations of Lee Myung-bak and Park Geun-hye.

The New Right’s interpretation of liberalism, influenced by global neoliberal movements, amalgamated market-oriented and pro-business ideologies with traditional anti-communist sentiments, leading to a nuanced understanding of liberal democracy that favored corporate and growth-centric principles. This ideological evolution influenced public party preferences and legislative activities, establishing the conservative party as a custodian of Jayu, reflective of a historical continuum from authoritarian regimes to contemporary conservative politics (Lee and You, 2019; Lee et al., 2018; Hong et al., 2023; Lee, 2023; Kim and Lee, 2023).

In contemporary discourse, the term Jayu transcends a singular historical or symbolic interpretation, reflecting the complex historical and political developments of Korea. The concept of Jayu has evolved, encompassing meanings from past authoritarian periods and those adopted during the post-democratization New Right Movement. This study posits that the concept of Jayu has been prominently featured in the narratives of conservative presidential administrations. President Yoon Suk Yeol, for instance, has openly declared “Ideology is the most important” as a guiding principle for the nation (KBS WORLD, 2023) and has critiqued the previous Moon Jae-in administration for adhering to what he perceives as flawed ideologies. Thus, President Yoon’s recurrent references to Jayu are deliberate, reflecting specific political motives and agendas. These references underscore the policy aims, foundational values, and ideological direction of the current conservative government, functioning as a means to express these elements. In the context of Korea’s “Imperial Presidency” paradigm (Dostal, 2023), the linguistic choices of the president significantly influence both institutional bodies and the public.

Presidential utterances, carefully constructed and refined, reveal the government’s objectives, administrative ethos, and presidential ideologies. Notably, key speeches, such as those at presidential inaugurations and international events, signal the government’s vision and indicate its strategic direction. This study’s thorough investigations shed light on the symbolic essence of Jayu, contributing crucial insights to the broader discourse regarding its complex symbolic meanings in the Korean social framework.