It might have been easy for former investment banker Adam Waters to build Canada's largest oil producer from scratch in just over six years through a series of acquisitions at a time of turmoil in the oil industry.

Waters, who all but secured billionaire status when he took Strathcona Resources Corp. public in October, is trying to bolster the company's shares at a time when oil producers face a host of headwinds. At issue is whether Strathcona can use its stock as currency to continue its acquisition-led growth spree.

The former top energy dealmaker at Bank of Nova Scotia is confident in his plan and says he's taking on the challenge partly to prove there can still be money to be made in an industry often blamed for its climate impact and overshadowed by flashier sectors like technology.

“If there's any wonder like, 'Who is this guy?' there should be more wonder like, 'What industry did he create that in?'” Waters, 62, said in an interview.

Waters declined to comment on his personal wealth, but a conservative estimate of his holdings detailed in securities filings values his Strathcona stake at more than $1 billion at current prices, largely due to his position as general partner in a fund that owns C$4.6 billion ($3.4 billion) of Strathcona stock.

He also owns other properties, including the Mount Norquay ski resort in Banff, Alberta, which he said he skied more than 600 times before buying it as part of “thorough due diligence.”

It would have been hard to predict what path Mr. Waterus would take when he left Scotiabank about seven years ago. He spent more than a decade there and served as head of the bank's global energy division before leaving to raise about C$400 million from investors to start an energy-focused private equity fund.

Waterus Energy Fund made a string of acquisitions of oil and gas producers at a time when the glory days of Canada's energy industry seemed over: Oil prices were falling, Alberta producers were struggling with a lack of export pipelines and international oil companies and investors were selling off their oil sands investments due to concerns about climate change.

The Waterus acquisition included assets such as Northern Blizzard Resources Corp., Kona Resources Corp., Pengrowth Energy Corp. and Cenovus Energy Corp.'s Tucker oil sands field. Strathcona then announced in August that it would acquire all of Pipestone Energy Corp. and take it public.

Strathcona currently produces 185,000 barrels of oil equivalent per day, making it one of Alberta's 10 largest producers. The company plans to increase production to 320,000 barrels per day over the next eight years, Watteraus said.

While Watteraus was already well known in Canada's energy industry from his days as a banker, Strathcona's rapid growth has caught the attention of U.S. investors.

“Who would do a backroom deal to go public?” Cole Smead, chief executive officer of Smead Capital Management, said in an interview about the unorthodox maneuver. “It's funny, but that's what Adam Waters is doing. That's the type of person you want to have leading some of the capital that we're giving them.”

Smead met Waters at the annual Calgary Stampede, a 10-day rodeo and festival that doubles as a networking event for the Canadian oil industry, and decided to invest in Strathcona if it went public. Phoenix-based Smead Capital is now the company's second-largest shareholder and has approached other funds about buying shares. Smead also plans to invite Waters and other Strathcona team members to Phoenix this winter to introduce them to more U.S. investors.

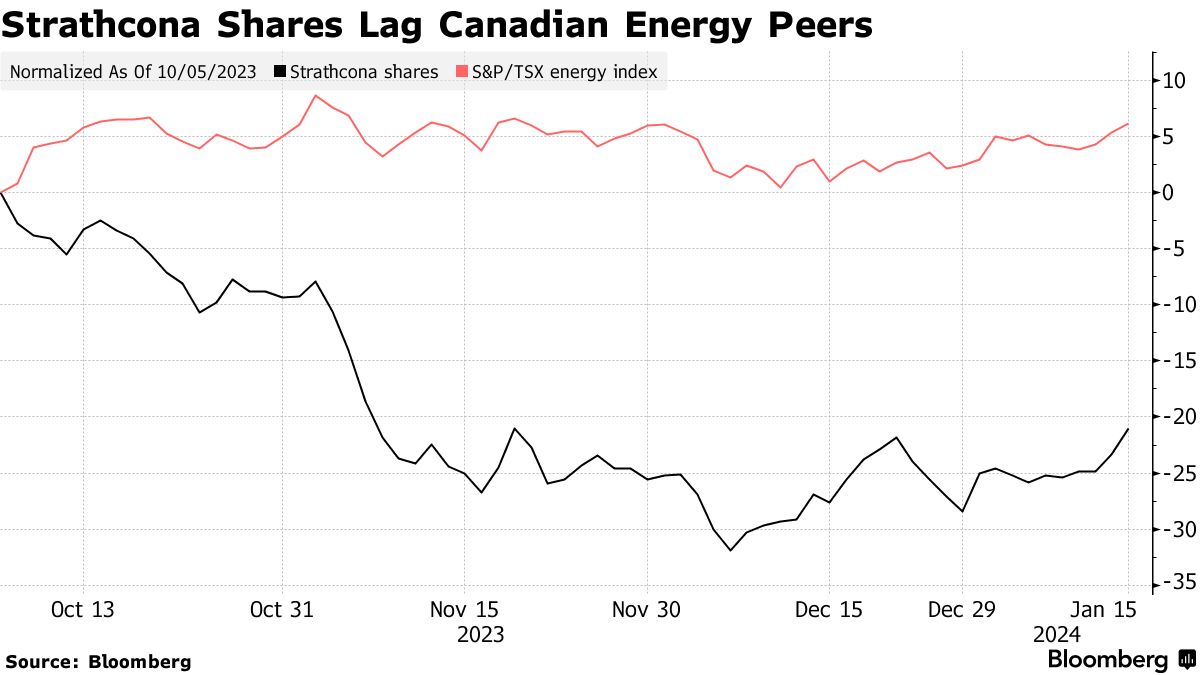

Strathcona's first few months as a public company haven't been without problems: The company's shares have fallen about 21% since its Oct. 5 debut, while the S&P/TSX Composite Energy Index has risen 6.2%.

Some of that is no doubt due to the 12% drop in oil prices over the period, but producers like Strathcona that don't have the scale of the international supermajors have their own challenges. Investors are increasingly favoring diversified oil giants that generate plenty of cash through dividends and share buybacks, rather than pumping money into expanding production like smaller drillers. And the entire oil industry is struggling with investor concerns about climate change.

A particular challenge for Strathcona is that its shares, 91% owned by Waters' fund, have limited liquidity. The company's price-to-earnings ratio is lower than other big Canadian oil producers and on par with smaller energy stocks like Toronto-listed Lucero Energy Inc. and Crew Energy Inc.

“Until they can raise the level of their shares outstanding, the stock will probably underperform,” BMO Capital Markets analyst Randy Olenberger said of Strathcona. Olenberger rates the stock the equivalent of “hold” and has a price target of C$25 a share, the low of the market.

Watrous said Strathcona is using 100% of its free cash flow to reduce debt and achieve an investment-grade rating. The company currently has a B1 rating from Moody's Investors Service, four notches below investment-grade. After that, the focus will shift to returning cash to shareholders, which will almost certainly include a dividend, he said.

Waterus said he expects shareholder turnover and a decline in the stock price as Pipestone Energy investors withdraw.

“Small investors are rushing out and larger investors are slow to get in,” Waters said. “It takes time to gain the confidence of larger investors.”