(Bloomberg) — Raising Britain's minimum wage risks having unintended consequences on inflation and employee benefits, putting Chancellor Keir Starmer's ambitions to raise wages at odds with business groups and the Bank of England.

Most read articles on Bloomberg

Business groups are already complaining that a 10% increase in the minimum wage (also known as the national living wage), which came into effect in April, is straining business budgets and limiting their ability to hire. Starmer's Labour government, which swept to power in last week's election, has pledged to review the wage floor to reflect a “true living wage”.

In her first major speech on Monday, Finance Minister Rachel Reeves said Labour wanted to create “a more prosperous country with better jobs paying a decent wage” and address “the causes of the cost of living crisis” to raise wages for working families.

But business groups, employment experts and economists say continued pressure to raise the minimum wage could fuel inflation, strain businesses and block more low-wage workers from programs designed to reduce child care and commuting costs.

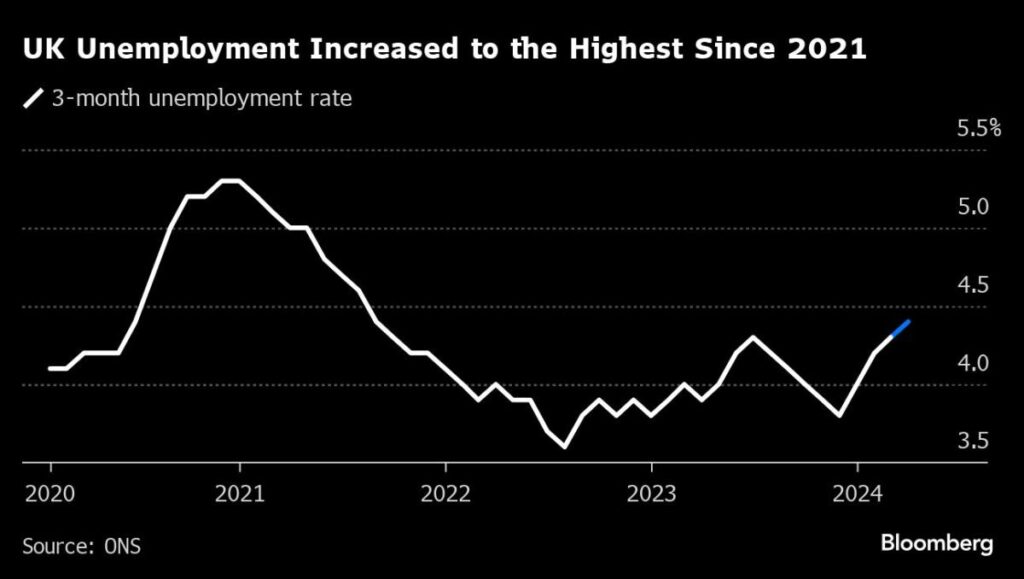

The previous Conservative government significantly raised the threshold for minimum wage earners, hoping that benefit recipients would be able to work if they did. Accelerating wage growth over the past two years has coincided with falling job vacancies and rising unemployment, suggesting business leaders may be holding off on further hiring.

The Bank of England is closely monitoring Labour's plans for wage increases before it meets in August to decide whether to lower borrowing costs, which are at a 16-year high. At its June meeting, the bank warned that a minimum wage increase “may have a larger-than-expected effect” on wages and prices in the broader economy because it would affect the wages of those at the top of the income bracket.

Policy maker Jonathan Haskell raised the issue on Monday, saying tight labor markets could keep inflation above target for the time being, justifying keeping rates on hold for now.

The regional agents and decision-makers panel “forecasts that the wage adjustment this year will be around 5%,” Haskell said. “This is a sign that the matching process between vacancies and unemployment is impaired. Any level of unemployment is therefore associated with an increase in vacancies and therefore increased wage pressures.”

The concern is that wage pressures will rekindle inflation and make authorities even more hesitant to cut interest rates.

“The impact on the Bank of England would be limited, but there is a risk that the pace of rate cuts would slow if Labour implements a significant increase in the living wage,” Goldman Sachs economists said in a note, adding that the policy “will likely pose the greatest source of risk to domestic companies with high labour costs.”

Business executives have warned that a higher minimum wage would force them to cut jobs and raise prices — and also limit their ability to raise wages for the rest of their workforce.

Currys chief executive Alex Baldock warned the policy could make it prohibitively costly for workers. The CBI, Britain's largest employers' body, has called for a new approach to raising living standards. The British Chambers of Commerce has said there are limits to how much employers can afford to pay.

Labour's pledge could be interpreted as either raising the minimum wage in line with inflation, or more drastically to match the real living wage, which could signal the minimum wage needs to rise from the current 66% to 70% of the median wage (according to the Resolution Foundation).

Many employees are also unhappy. British workers can give up some of their pre-tax income to access benefits like extra holiday days, cycle schemes, childcare vouchers and extra pension contributions, so long as their pay sacrifices don't fall below the national minimum wage. A sharp increase in the floor has widened the pool of people earning at that level who are no longer eligible for such benefits.

“It's unfair that low-paid workers don't have the same access to payroll deduction benefits as their more highly paid colleagues,” said Charles Cotton, senior remuneration adviser at the UK Institute of Personnel and Development. “Chief executives can get payroll deduction but office cleaners and security guards can't because they don't earn enough.”

Labour group Unison said the lack of pay increases had meant some NHS staff, including porters, healthcare assistants, cleaners and 999 call takers, were “losing access to support schemes they have had access to for many years”.

“They're going to have to now pay more for childcare, season tickets and parking,” Unison's health director Helga Pyle said.

Employers are increasingly struggling to raise wages at the pace required by law, causing more jobs to fall into the minimum wage category. The Minimum Wage Board estimates that as a result of the minimum wage increase, the number of minimum wage jobs is expected to reach 2 million, up 25 percent from 2023, representing about 7 percent of all workers.

“This will be the second year in a row that we've seen an increase of over 10 percent, which is a big deal for a lot of employers,” said Stuart Hyland, compensation services partner at Brick Rosenberg L.P. “We're now targeting people who were making 20 percent above minimum wage two years ago, and that target is getting bigger and bigger.”

British car dealer Virtue Motors recently said the policy had doubled the proportion of workers making within 5% of the minimum wage to nearly a quarter, and cited a lack of access to pay reduction schemes as a key cause of growing employee dissatisfaction. Employment experts also warn that minimum wage workers do not feel rewarded for their extra efforts.

The problem is particularly acute in retail and hospitality, where a high proportion of workers are on the minimum wage, and it comes as inflationary pressures on wages generally rise – an issue the Bank of England is watching closely.

One alternative would be to implement targeted tax cuts for those at the bottom of the income bracket, Hyland said, but because Labour stuck with the Conservative stealth tax and chose to leave income tax rates unchanged from 2021 rather than raising them in line with inflation, the opposite is happening – meaning fewer workers will fall into the lowest income bracket each year.

“We need to put more money in the pockets of the poorest people in society, but there are question marks in the minds of many employers about whether this is the right way to go about it,” Hyland said. “Someone somewhere has to pay, and we know that's just going to drive up prices.”

–With assistance from Jamie Nimmo and Andrew Atkinson.

Most read articles on Bloomberg Businessweek

©2024 Bloomberg LP