The United States Constitution requires that the president must be at least 35 years old, but there is only a minimum age limit; there has never been an upper age limit.

Carolyn Custer/AP

Hide caption

Toggle caption

Carolyn Custer/AP

Over the past two weeks, President Biden has come under fire from all sides for his performance in the recent CNN presidential debate, which many perceived as weak and faltering. His subsequent public comments have not dampened calls for him to drop out of the race, leaving a question on the minds of many voters: Is it possible to be too old to be president?

Biden and former President Donald Trump are the two oldest major-party candidates voters will see on the ballot: If Biden wins, he will be 82 on Inauguration Day; Trump will be 78.

There is a complex relationship between age and intellectual ability, but a candidate's age influences voters' perceptions of how well they can perform their jobs.

That was true even before the debate: An April report from the Pew Research Center found that only 15% of voters were at least “very confident” that Biden had what it took to be president physically, and 21% felt the same about his mental strength. (Trump fared better, with 36% expressing that level of confidence in his physical strength and 38% expressing that level of confidence in his mental strength.)

Donald Trump, Barack Obama and Joe Biden gather at the U.S. Capitol after Trump was inaugurated as president in 2017.

Mark Ralston/AFP via Getty Images

Hide caption

Toggle caption

Mark Ralston/AFP via Getty Images

The Founding Fathers certainly thought about presidential age centuries ago: It's enshrined in Article II of the U.S. Constitution, which among other things requires that a president must be at least 35 years old. But while there are age limits for who can hold office, there's never been a rule about how old a president can be.

Currently, about 80% of American adults surveyed support setting an age limit for federal elected office, including the presidency, according to the Pew Research Center. But constitutional law experts say the architects of the U.S. government in the 18th century would never have conceived of such a restriction, and there are significant obstacles to changing those rules anytime soon.

Age was just a number at the Constitutional Convention

The Constitutional Convention, which met in Philadelphia in 1787, is still remembered for being filled with the fierce debates that shaped the Constitution. It's easy to assume that the age limit was similarly the product of a lot of time and deliberation. But that wasn't necessarily the case. After all, the Founding Fathers were busy building an entire government from scratch, says Julian Davis Mortenson, a constitutional law professor at the University of Michigan.

“The problems they had to solve were literally endless,” he says. For one, should there be an executive branch at all? Should there be just one president or multiple leaders? And how would the leader be chosen?

“And even a four- or five-month drafting process can only go so far. Some of the things they thought about were things they thought about a lot. And some things just didn't come up.”

When the Founding Fathers settled on the idea of a single, powerful executive, they were clear they needed someone trustworthy and competent to fill that role, Mortenson said.

So how do you screen them? The Founding Fathers devised formal requirements that, in their view, correlated with those qualifications, says Buckner F. Melton Jr., a history professor at Middle Georgia State University: They had to have lived in the United States for at least 14 years to ensure they were familiar with the country's laws and customs, and they had to be natural-born U.S. citizens to protect the presidency from outside influence.

The minimum age limit was set because “age was the most appropriate test of sound judgment, maturity and so-called wisdom,” Melton said, and they chose 35, slightly higher than the requirements for the Senate (30) and the House of Representatives (25).

So why have a floor but no ceiling? Melton says that in reviewing all the meeting materials, the idea never occurred to him. He has a hypothesis: Life expectancies were much shorter in the 18th century than they are today, so the idea of someone running for political office at the age when they're least mentally healthy probably never crossed the Founding Fathers' minds.

The president's age and mental capacity have become more important

As time goes on, Melton says, industrial-era medical advances like antibiotics and disinfectants mean people tend to die longer than they used to, and as presidents live longer and suffer more disabling medical emergencies, questions of fitness to do their jobs begin to emerge.

President Woodrow Wilson and his wife, Edith Wilson, circa 1916.

Topical Press Agency/Getty Images/Hulton Archive

Hide caption

Toggle caption

Topical Press Agency/Getty Images/Hulton Archive

President Woodrow Wilson, whose stroke at age 63 in 1919 left him “severely hindered” in his work, became emblematic of those concerns, Melton says. Wilson was mostly bedridden for the first year and a half of his presidency, and his wife, Edith Wilson, and his doctors played key roles in helping him with his duties, without the public knowing about them. (Just how much they did is up for debate — Edith Wilson said in her autobiography that she “never made any decisions regarding the disposition of any official duties,” but most historians agree that she had a major influence on Wilson's decision-making.)

According to Mortenson, it was clear to Wilson's cabinet that he had no intention of stepping down and replacing the presidency with someone else, even the vice president, and there wasn't much anyone could do about it. After all, the Constitution said what happened when a president died, but it didn't say what happened when his presidential abilities were significantly diminished.

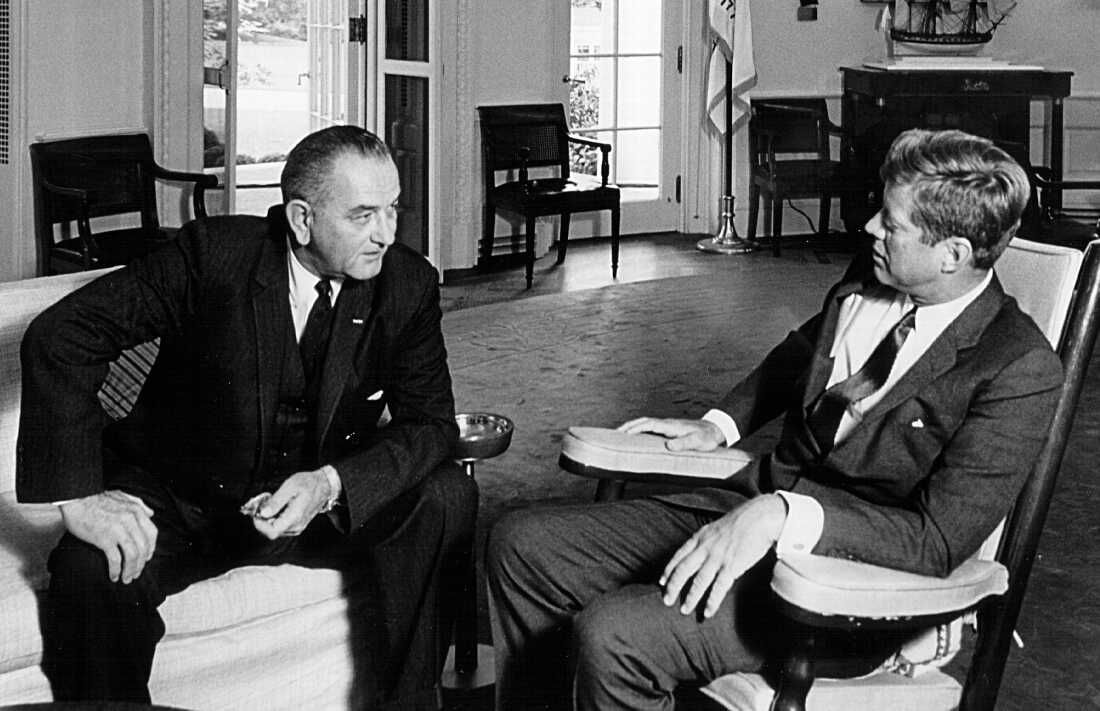

These questions would continue to loom for decades to come, especially when President Franklin D. Roosevelt's health rapidly declined and he died in office in 1945 at age 63, and when President Dwight Eisenhower suffered heart attacks and other serious illnesses in the 1950s. But things reached a turning point in 1963 when President John F. Kennedy was assassinated and Lyndon B. Johnson was sworn in. There were concerns about the stability of the line of succession. At the time of his assassination, Johnson had suffered a near-fatal heart attack a few years earlier, and the Speaker of the House and President pro tempore of the Senate were 71 and 86, respectively.

President John F. Kennedy and Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson in the Oval Office in September 1963, two months before Kennedy's assassination, raising concerns about the stability of the line of succession.

The National Archives/Getty Images/Hulton Archive

Hide caption

Toggle caption

The National Archives/Getty Images/Hulton Archive

“When you have a concrete, real-world event that creates fears about what would happen if the president were no longer able to do his job, it creates a political response,” Mortenson said. In this case, that response was the 25th Amendment, ratified by the states and adopted in 1967.

The 25th Amendment, among other things, provides how the vice president takes over if the president is unable to perform his duties, and it also provides a procedure for removing an incompetent president from office by the vice president, a majority of the Cabinet, and a supermajority of Congress.

The stripping portion of the amendment has never been invoked, even though it was reportedly considered by at least some advisers given claims that President Ronald Reagan's mental health had deteriorated during his second term. (Reagan announced his Alzheimer's diagnosis in 1994, five years after leaving office; at the time, he was the oldest president to leave the Oval Office, at age 77.) The issue also came up after the January 6 riots, when Sen. Chuck Schumer (D-NY) and other Democrats on the House Judiciary Committee called on then-Vice President Mike Pence to invoke the 25th Amendment to strip Trump of his powers.

But the amendment comes the closest politically to addressing concerns about the president's age and mental capacity, Mortenson said.

What would it take to implement a presidential age limit?

While polls show widespread support for an age limit, changing the requirements to become president faces a major hurdle: The Constitution itself would have to be amended before the rules could be upheld in court, Mortensen said.

The bar for passing an amendment is notoriously high: it must receive two-thirds support from both the House and the Senate, or two-thirds of the states must petition Congress to call a constitutional convention. From there, an amendment must be ratified by three-quarters of the nation's state legislatures before it becomes part of the U.S. Constitution.

Melton said it's unlikely Congress would support changing the age requirement for president because serving in the House or Senate is often a stepping stone to the presidency.

“If Congress hesitates to impose an age limit because it thinks it might insulate them from the White House, a conference of states would be the only solution,” he said, “and Congress has shown in the past that it is willing to put roadblocks in the process.”

This is not just a political question, but also a neuroscience question. The most basic question is: What is the limit? There is no set age at which a person's cognitive abilities decline, and some people experience very little decline at all. Alternatively, others, including Reagan's daughter, have suggested using some kind of cognitive test as a benchmark.

“We need to come up with a very solid, agreed-upon, empirically-based, verifiable, reliable test to determine whether someone is too old,” Melton said. “Obviously, the other thing we can do is draw a clear line at 70 and that's it. We do that for retirement. Why not in the White House?”

Whatever the solution, he says, voters seem to have come to a consensus of sorts: “The country is so divided right now, but … there's a strange unity in that everyone, whatever their political stance, recognizes that the presidential candidate may be too old.”