For more than a century, Texas' economy has depended on oil. Images of giant geysers spewing depreciating wealth from the earth are forever linked to the state. In the public imagination, wealthy Texans are invariably oil tycoons. These formations beneath Texas' surface — Austin Chalk, Barnett Shale, Wolfcamp — have produced so much black gold that their names are known to oilmen and ordinary citizens alike.

Largely due to high oil prices, Texas has generated more than half of America's economic growth over the past decade. The state's $1.6 trillion gross domestic product would place it around 10th in size if it were a separate country, bigger than Canada or Australia. California has 40% more people and a $2.6 trillion GDP, but since 2000, Dallas and Houston have both grown jobs by about 30%, three times faster than Los Angeles.

Texas' strong growth was thwarted when oil prices, which rose to $145 a barrel in 2008, collapsed in 2014 and eventually fell below $30. In 2016, the state's job growth lagged the nation's for the first time in 12 years. Houston, the world's oil and gas capital and home to 5,000 energy companies, saw its oil price collapse show up in vacant office buildings and slowing home sales. Even traffic on the highways slowed.

Between January 2015 and December 2016, more than 100 U.S. oil and gas producers declared bankruptcy, nearly half of them in Texas. That doesn't include the economic impact on pipeline, storage, service, and transportation companies that rely on the energy business, or the $74 billion worth of debt those bankruptcies have created. As a gesture of sympathy, Ouisie's Table, a restaurant in Houston's affluent River Oaks neighborhood, began offering a three-course menu on Wednesday nights pegged to the price of a barrel of oil. When I visited in early spring 2016, the menu cost about $38. (Ouisie's Table stopped the practice as oil prices crept up. As of December 13, the Wednesday special was priced at $56.60.)

Now that oil prices have stabilized, Texas' economy is booming again. In recent years, the state has finally begun to diversify, and is now outpacing California in technology exports, from semiconductors to communications equipment. Conservative Texas politicians like to claim that the state's low taxes and light regulations are the magic driving force behind its economy. But oil still sets Texas apart. It has been both a blessing and a curse.

The epic story of Texas oil is actually about three oil wells. In the early 20th century, near Beaumont (on the Gulf Coast near the Louisiana border), there was a sulfurous hill called Sour Spring Mound. Natural gas constantly seeped to the surface, and sometimes boys would set the hill on fire. Pattillo Higgins, a disreputable local businessman who had lost an arm in a shootout with a deputy sheriff, was convinced that oil was buried beneath it. In those days, oil wells weren't drilled; they were basically hammered into the ground, with a heavy bit repeatedly lifted up and down to chip away at the formation. There was quicksand beneath Sour Spring Mound, which made any attempt to dig a stable hole difficult. Still, Higgins persisted, predicting that the well would be found 1,000 feet below the surface, a number he made up.

In 1898, Higgins hired mining engineer Captain Anthony F. Lucas to drill a well at Sour Spring Mound. Lucas's first attempt only drilled 575 feet before the pipe collapsed. He decided to try a new device called a rotary bit, which proved better at penetrating softer formations. Drillers at the site also discovered that pumping mud down the hole formed a kind of concrete that reinforced the sides. These innovations gave birth to the modern drilling industry.

Lucas and his team hoped to drill a well that would produce 50 barrels of oil a day. On January 10, 1901, at a depth of 1,020 feet (a depth that Higgins had almost exactly predicted), the well suddenly spewed mud, followed by six tons of drill pipe from the top of the derrick. No one had ever seen anything like it, and it was terrifying. In the uneasy silence that followed, the drilling team, covered in mud, crept back to the site and began to clear the rubble. Then, from millions of years ago, they heard a roaring sound deep underground. More mud blew up, followed by rocks and gas, followed by oil spurting 150 feet into the air. A black fountain gushed from the arterial wound the drillers had made. It was the largest oil discovery in history. For the next nine days, until the well was capped, the well gushed 100,000 barrels of oil a day. This was more than the production of all the other oil wells in America combined. After a year of operation, the well, which Higgins named Spindletop, was producing 17 million barrels of oil per year.

At the time, Texas was almost entirely rural. There were no big cities, virtually no industry, and cotton and cattle were the backbone of the economy. Spindletop changed that. Native Texans were suspicious of outside interests, especially John D. Rockefeller's Standard Oil, so two local companies, Gulf Oil and Texaco, were formed to develop the new oil fields. (Both companies later merged with Chevron.) The oil boom made some prospectors millionaires, but the sudden oil glut wasn't entirely a blessing for Texas. The 1930s saw oil prices crash, making oil cheaper than water in some parts of the U.S. This was the beginning of a boom-and-bust pattern for the Texas oil economy.

In August 1927, prospector and crooked conman Columbus Marion Joyner, known colloquially as “Dad,” began drilling on the Daisy Bradford lease in East Texas, named after the widow who owned the land. Joyner had very little money and no luck. His first two wells failed. To lure investors into drilling more wells, Joyner created fake geological reports suggesting the presence of salt domes and folds of strata that could hold oil and natural gas deposits. The fake reports claimed that a 3,500-foot-deep well would access one of the largest oil deposits in the world. Once again, his bold predictions came true.

Dad Joyner was after Woodbine Sand, which sits atop the Buda Limestone and is packed with fossils of dinosaurs and crocodiles that roamed the shallow seas of the Cretaceous Period. Over millions of years, plankton, algae, and other materials buried in the sand were transformed into oil and gas. For three and a half years, Joyner scraped by, paying his workers in paper money. To raise enough money to complete the well, he sold $25 stock certificates to farmers. When Daisy Bradford No. 3 reached 3,456 feet, a core sample finally revealed the oil-soaked sand. Thousands gathered to watch the savage drillers and swabbers work through the night. The locals, farmers in bib overalls and women in dresses sewn from patterns from Sears Roebuck catalogs, envisioned a life of fine clothes, strolling the boulevards, checking the prices of jewelry, and considering investments. That dream was about to become a reality for many of them. Late in the afternoon of October 3, 1930, a gurgling noise was heard. At eight o'clock, oil began to spurt into the air, followed by a loud gush. People danced in the black rain, and children smeared oil on their faces.

Overnight, new prospectors and big oil producers arrived. Within nine months of Daisy Bradford No. 3, the East Texas oil fields had 1,000 wells in operation, accounting for half of the U.S.'s total production. Towns sprang up to accommodate saloons, hotels, and camps to entertain the roughnecks. Existing cities like Tyler, Kilgore, and Longview suddenly found themselves in a forest of towering oil wells that jutted out of their backyards and overlooked the downtown buildings. Texans pumped so much oil from Woodbine that the price, which had peaked at $1.10 a barrel, plummeted to 13 cents. The governor tried to raise the price by shutting down the wells. In 1930, Joyner, plagued by lawsuits for years of reckless promises, sold his lease interest in Daisy Bradford to H.L. Hunt. Hunt later became the richest man in the world. Joyner went bankrupt in 1947 and died in Dallas.

By the mid-1990s, the U.S. oil business was stagnating. The industry seemed to be on the brink of peak oil, the moment when at least half of the world's recoverable oil has been extracted. Beyond the peak lay a steep slope of diminishing returns. Big oil companies began to focus their exploration efforts outside the U.S., where reserves were deemed nearly exhausted. The end of the fossil fuel era, while not exactly imminent, was no longer inconceivable.

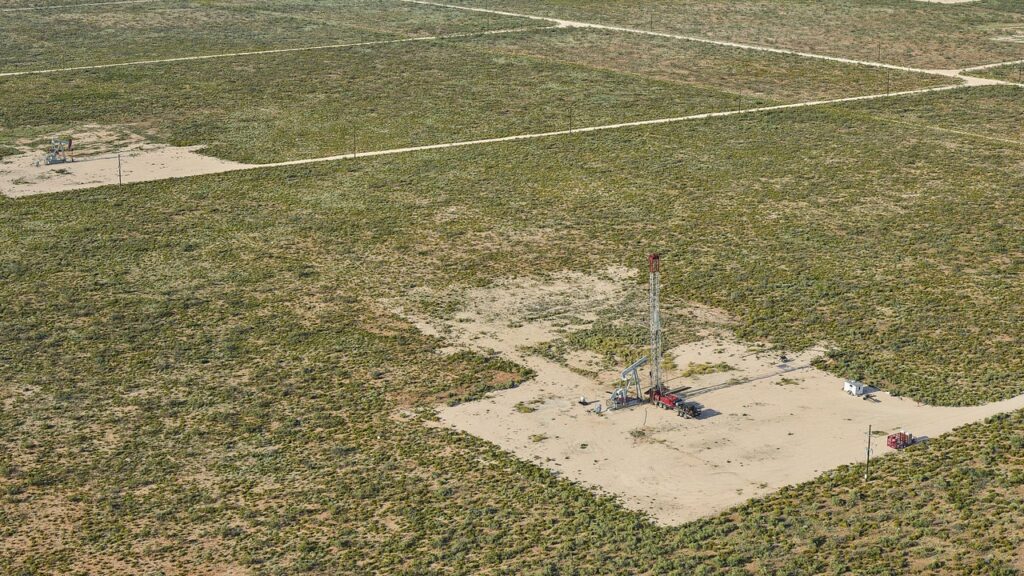

A gas plant under construction in Aula, a ghost town on the Texas-New Mexico border.Photo by Andrew Moore for The New Yorker

For George Mitchell, the situation was brutally clear. He became one of Texas' greatest go-getters. The son of Greek immigrants, his father, who changed his surname from Paraskevopoulos to Mitchell, owned a shoeshine shop in Galveston. George studied geology and petroleum engineering at Texas A&M University, graduating summa cum laude. In 1952, acting on a tip from a bookmaker, he signed an option on land in Wise County, an area known as the “graveyard of go-getters” in North Texas. He soon owned 13 oil wells, the first of the 10,000 he would develop.

In 1954, Mitchell won a contract to supply 10 percent of Chicago's natural gas needs. But production from wells operated by his company, Mitchell Energy & Development, was declining. He needed to find new oil sources; otherwise, Mitchell was convinced the world was running out of fossil fuels. In 1980, he predicted that the United States had only about 35 years' worth of traditional oil sources left. The obvious alternative was coal, with its severe environmental impacts.

Mitchell's main asset was a lease on 300,000 acres of land 70 miles northwest of Dallas, in an area known to oilmen as the Fort Worth Basin. A mile and a half below the surface lay a layer called the Barnett Shale. Spanning 17 counties and covering 5,000 square miles, geologists estimated that the Barnett contained the largest reserves of any onshore gas field in the United States. The problem was, no one knew how to extract the gas. Porous formations like the Woodbine sand that Uncle Joyner mined allow liquids and gas to flow, but the Barnett Shale is “tight rock,” meaning it has very low permeability. In the mid-20th century, prospectors tried to break up the tight rock to free the oil reserves. Dynamite, machine guns, bazookas, and napalm were all tried, without success. In 1967, the Atomic Energy Commission, working with Lawrence Livermore Laboratory and the El Paso Natural Gas Company, detonated a 29-kiloton nuclear bomb called the Gas Buggy 4,000 feet below the surface near Farmington, New Mexico. More than 30 nuclear explosions followed, known as Project Plowshares. It was discovered that natural gas could be extracted from the atomized rubble, but the gas was radioactive.