This interview our David Brancaccio Special Lecture Series on Economics: Documentary Studies, One We will discuss economic lessons that can be learned from documentaries. Each month we will watch and discuss a new documentary. To watch together: sign up Subscribe to our newsletter.

It turns out that having a lot of money doesn't necessarily make you more likely to share it with others. In fact, research suggests the opposite.

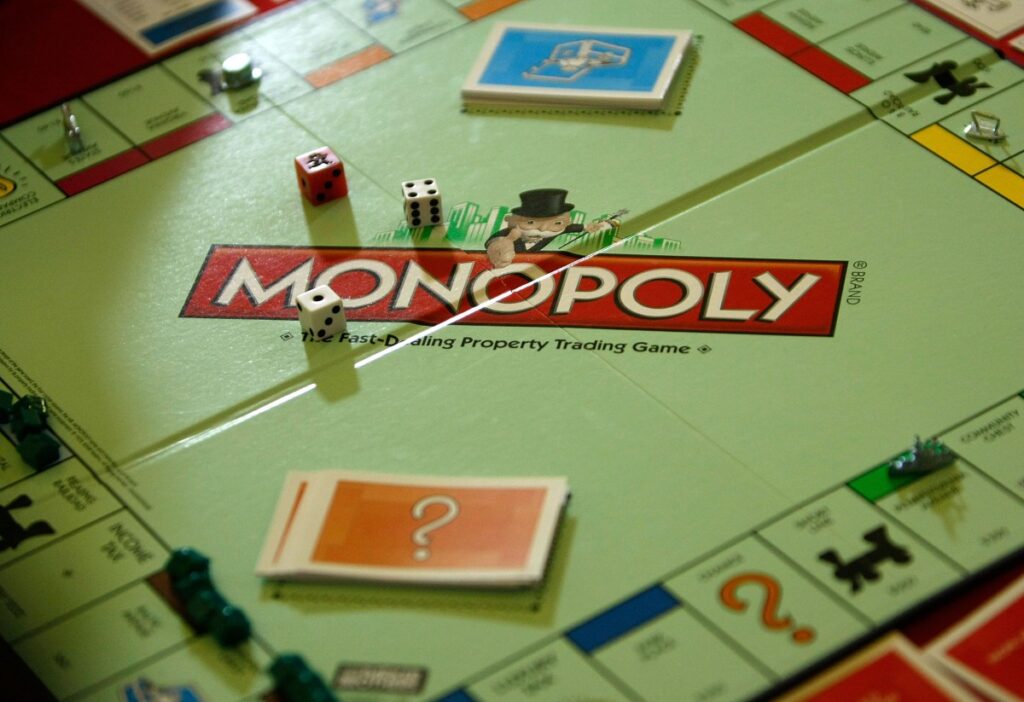

In an experiment conducted by psychologists at the University of California, Irvine, strangers were paired up to play a rigged game of Monopoly in which a coin was flipped to determine who was rich and who was poor. The rich player started off with twice as much money as their opponent. As the game progressed, they were able to roll two dice instead of one, and they moved around the board twice as fast as their opponent. When they passed “Go,” the rich player won $200 compared to their opponent's $100.

“So it could be that the rich players feel embarrassed about the situation and are doing what they can to help the other, unfairly poor players, which is actually the opposite of what we found,” said Paul Piff, the psychologist who conducted the experiment. (Piff appears in the film “Capital in the Twenty-First Century,” which we're watching as part of the Special Economics Project.)

In a variety of ways — through body language, boasting about their wealth, the sound of their pieces slamming against the board, downplaying their opponents' bad luck — the wealthy players began to act as if they had been blessed with good fortune, which was primarily the result of a lucky roll of the dice.

At the end of the game, when the researchers asked the wealthy players why they won the game, not a single one attributed it to luck.

“They don't talk about the coin toss. They talk about what they did. They talk about their insight and their ability. And they talk about this decision or that decision that helped them win,” Piff said in an interview with host David Brancaccio.

Piff said the experiment revealed a fundamental bias that most humans share.

“When something good happens, we think about the things we did that contributed to that success,” Piff said.

This could be problematic, as inequality has risen sharply in developed countries in recent decades.

“This approach gets those who are winning in the game of life – those with more money, more privilege, more power – to think of their resources as something they deserve. After all, because they deserve what they have, they are less likely to see inequality as a problem and therefore less motivated to take action about it,” Piff said.

Below is an edited transcript of the conversation.

David Brancaccio: If you flip a coin and one player ends up doing well and the other player doesn't, what happens to the player who did well? Does he get angry?

Paul Piff: Right. What's remarkable is that after just a few minutes, the dynamics start to become clear. The rich players start taking up more space at the table and actually assuming more physical positions. They start making more noise. They start banging their pieces on the table more loudly as they move around. And one of the things we noticed over the course of 15 minutes is that their behavior actually became more rude.

One possibility is that the rich players feel embarrassed about the situation and are doing all they can to try to help the other players, who are unfairly poor players. This is actually the opposite of what we found. The rich players became more rude and insensitive to the plight of the other players. They started eating more pretzels and did so in a more rude manner. We found another way to observe the dominance of the rich players by putting bowls of pretzels on the table. They started to flaunt their possessions and wealth and show how well they were doing.

So across all these different metrics, we see that the rich players behave as if they deserved to win and the poor players deserved to lose, even though they won the game with little effort because the coin toss result was in their favor.

Brancaccio: They think that's how great they are. You have to love human beings, don't you? We are such a wonderful people.

Piff: And I think that's the clincher. At the end of the study, when we asked the wealthy players why they inevitably won, they didn't talk about the coin toss. They talked about what they did. They talked about their insight, they talked about their abilities, they talked about this decision or that decision, what they did.

I think this is a basic human bias that applies to all of us. When something good happens, we, thanks to the cognitive mechanisms we have in place, think about the actions of our own that contributed to that success. And we see it in people who win in all areas: when they are winning, they think about the actions that contributed to their victory. The problem is that when this bias is widespread, at least in the area of inequality, the people who are winning in the game of life – those who have more money, more privileges, more power – are more likely to see their resources as something they should deserve and to see inequality as a problem. Because, after all, they deserve what they have. And as a result, they are less motivated to act on inequality, less motivated to contribute to those who have less, less motivated to act in a compassionate way or to respond to the needs of those who have less than them.

Brancaccio: And we can see why it's so difficult to address the growing inequality we see, but we must remember that life is not a completely random game of Monopoly: sometimes, working harder pays more.

Piff: I think that's absolutely true. There are obviously a lot of situations where wealthy people or privileged people have contributed or have contributed to create the resources and privilege that they have. But I think it's a universal truth that for all people, there are times when they benefit from things that they didn't contribute to. They benefit from things that they didn't build, they benefit from things that they didn't create. They benefit from the paths that were paved for them, the people that helped them along the way, the mentors that they happened to be in the same class with. And it's these key elements that we're trying to highlight in our recent research. It gets people to think about how, whatever they've done to create the power or the success that they have, they've inevitably benefited from the help of other people, and it in turn gets people to think about the fact that other people may be less fortunate, and it inspires them to be more willing to contribute to their own benefit.

Brancaccio: I thought maybe the subjects in the Irvine, California area were just particularly selfish fools, but you've tested this elsewhere too.

Piff: Yes, we've done similar studies in South Africa, we've done some similar studies in Europe, and in the different contexts in which we've done this experiment, or versions of the experiment where people are randomly privileged or disadvantaged, we see very similar differences in which people who benefit from the coin toss suddenly start thinking that they deserved to win.

Brancaccio: So you're doing some really interesting research in your lab, namely, looking at the concepts of inequality and altruism. Can you tell us a little bit about what you're working on now?

Piff: Yeah. One of the things that we're really interested in is, if inequality is partly perpetuated by the prejudices that stem from inequality in the first place, then what are some simple psychological levers that we can use to get people to think about the fact that life might not be fair, and that something like a global pandemic can happen that, through no fault of their own, suddenly causes people to experience suffering, or, say, poverty or unemployment?

And by getting people to think about these potentially unfair, unjust and unjust world events and outcomes in their lives, can we shift the way we think about what happens to people, the circumstances in their lives, and ultimately what happens to them, not as something that is unfair and unjust, but something that might justify individual, societal, and even government intervention?

There's a lot going on in the world, and Marketplace is here for you.

Marketplace helps you analyze world events and bring you fact-based, easy-to-understand information about how they affect you. We rely on your financial support to keep doing this.

Your donation today will power the independent journalism you trust. Help sustain Marketplace for just $5 a month so we can continue reporting on the things that matter to you.