Michael J. Hicks

Many economic development leaders and elected officials think of their states and cities like businesses: They work on economic development policies, trying to make their regions competitive by offering tax incentives and direct subsidies. They also worry about their image, trying to sell their communities as if they were products or services.

This approach is rational and easy to explain, but it is a universal failure.

Hicks:Republican areas will become poorer and Democratic areas will become richer.

Indiana is a cheap place to hire workers (shockingly high health care costs aside), is conveniently located on a major transportation artery, and has perhaps the lowest business taxes and regulatory burdens in the country. If Indiana is a business, you're sure to be thriving.

On the contrary, our economy has lagged the nation as a whole since World War II, and the past two decades have been the worst relative economic performance on record.

California and New York beat Indiana

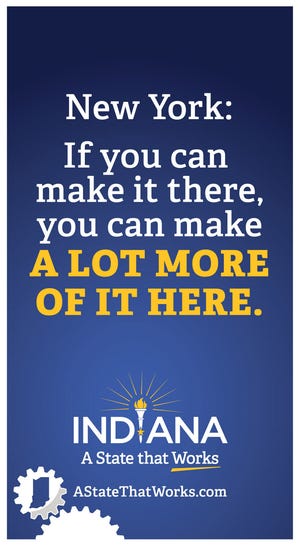

What's more, Indiana lags behind states that cable TV pundits joke about, like California and New York, which have dwarfed Indiana's growth for decades: Last year alone, California's growth rate was 51% higher than Indiana's, and New York's was 65% higher.

Adjusted for inflation, the average Hoosier has a lower income than the typical Californian in 2005 and the typical New Yorker in 2006. This means that the per capita income of a Hoosier differs from that of a Californian by more than $20,000 per year and from that of a New Yorker by more than $11,000 per year.

So how does a business analogy compare?

California and New York have much higher tax rates than Indiana, but rising health care costs offset much of the benefit. Land and construction costs are expensive in California and New York. The regulatory environment for business is surprisingly tough in California and New York.

But Indiana is losing population to California and New York: for every 10 Hoosiers who move to California, six Californians move to Indiana, and for every 10 Hoosiers who move to New York, three New Yorkers move to Indiana.

The “human capital” effect

It's still fun to poke fun at people in California and New York, but it's delusional to believe that Indiana has some economic magic that they don't. Something else is going on, and when you understand how economists look at economic growth, it becomes painfully clear what it is.

Modern economic explanations for regional growth differences date back to the 1950s, when rapid decolonization was underway and economists pondered the wealth disparities in many parts of the world. The best way to explain the world was that capital (productive machines and equipment) flows from rich to poor regions in search of higher rates of return.

This idea, expressed as a mathematical model, won Robert Solow a Nobel Prize. His theory argued that, at the margin, in poor, capital-scarce areas, extra trucks, lathes, and bridges could produce higher rates of return. At the time, there was a widespread, truly optimistic view of world poverty.

But by the late 1970s, the model's main prediction – that poor regions would grow faster than rich regions – began to fail. Instead, rich regions tended to get richer while poor regions stagnated. Injections of capital into poor countries in Africa and Asia did not produce the expected growth. This was a profound mystery.

In the 1980s, a different group of researchers added a measure to this model called “human capital,” meaning improvements in education, skills, and health. In practice, the only thing that could be measured to feed into the equation was the educational attainment of a population.

This simple addition produced astonishingly accurate predictions, and today variations on this approach explain most of the differences in living standards, worker productivity, and economic growth rates between continents, nations, states, and counties.

Education trumps economic development

To put it as simply as possible, education levels are now a stronger predictor of a region's economic success than all others combined. In developed countries like ours, there are two key elements of education that make a difference in growth.

Naturally, the first step is to have the ability to educate the local existing population. Places with a well-educated population tend to do very well economically, and the reason is simple: education tends to make workers more productive.

Of course, this isn't universally true (as faculty meetings will amply demonstrate), but it is true on average: More productive individual workers earn higher starting wages and higher lifetime wages.

It is clearly true that college graduates earn more than non-college graduates, but that only tells part of the story.

High school graduates can also expect significant wage increases if they live in a city or state with a higher percentage of college graduates: If Indiana were to move up from its current educational attainment ranking of 41st to the national average, the typical Indiana high school graduate would see a 5.3% increase in wages.

The reason wages rise like this is simply because less educated workers are more likely to be in environments with more productive workers. It also means there are fewer less educated workers around. This combination makes more educated places prime destinations for people without a college degree.

The second reason that education tends to have dramatic benefits for a region is because strong education systems have the ability to attract educated people. Nearly all net migration in the United States is from less educated counties to more educated counties.

Even the widely reported migration of Californians to Texas has been driven mostly by people moving from less educated parts of California to Austin, Dallas, and Houston, where 60%, 45%, and 33% of adults have a bachelor's degree or higher. The California counties with the greatest migration losses have only 22.5% of adults with a bachelor's degree.

The Midwest has lagged the nation in growth for 40 years, all the while employing economic development strategies from the 1950s and 1960s that showed no evidence of success even then. In recent decades, nearly every Midwestern state has doubled down on that strategy, with deeply problematic projects such as Foxconn in Wisconsin and the LEAP districts in Indiana.

These failed business attraction strategies have come at the same time as major cuts to funding for education, particularly higher education. If a Bond villain were to design policies to ensure the long-term economic decline of the developed world, it would be two-fold: first, spending billions on corporate incentives that provide a false narrative of economic recovery, and second, cutting education spending.

Welcome to the Midwest circa 2024.

Michael J. Hicks is director of the Center for Business and Economic Research and the George and Frances Ball Distinguished Professor of Economics in the Miller School of Business at Ball State University.