Being rich is a relative measure, not an absolute measure of wealth. It's not a sign of abundance, it's a sign of inequality. Historian Guido Alfani argues in As Gods Among Men: A History of the Rich in the West that this is why there is a lasting discomfort about wealth. This book uses recent data on inequality to examine forms of wealth over the past 1000 years, exploring attitudes towards the rich and how they behave.

Nobility, entrepreneurship and finance are the traditional routes to money. Aristocrats with publicly recognized status have always had privileged access to resources. However, after the commercial revolution of the Middle Ages, as large merchants became wealthy in Italy and other countries, a backlash began.

In Christian tradition, the super-rich were thought to be sinful, greedy, and trying to be more divine than other people. They had to hide the extent of their wealth. Many sought to save their consciences by seeking religious absolution or donating to charities or churches. The wealthy were given the responsibility of carrying the population through times of crisis, epidemic, and famine. During the war, the king often forced businessmen to take out loans. Even in World Wars, the wealthy were expected to contribute.

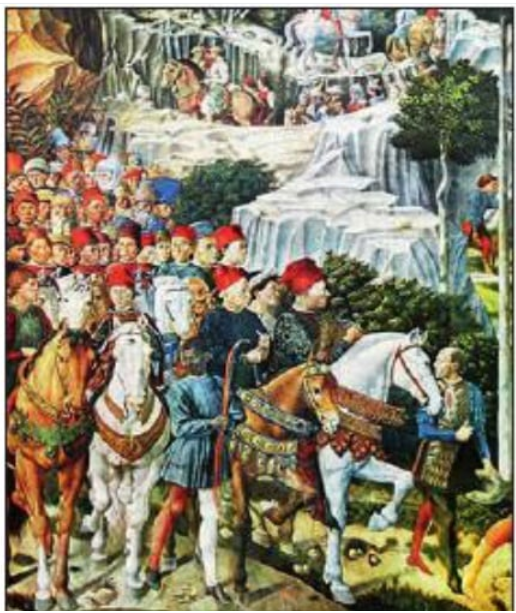

The lavish use of wealth was used to separate the good and wealthy from the wretched sinners. This is also why families like the Medici family chose to build great cathedrals for the public, a “grand” act that made a huge contribution to displaying moral and economic greatness. These acts also entrenched their role in broader society and politics. At a time when public welfare spending was low, this planned spending by the wealthy provided a comfortable life for the poor.

After the Industrial Revolution, the newly wealthy class of the 19th century and beyond had no restrictions on ostentation. In fact, conspicuous consumption was essential to demonstrate status. America's “robber barons” and prominent dynasties were more obsessed with generosity than with luxury – voluntary giving without any sense of obligation.

The wealthy, then and now, prefer ostentatious donations over taxes, and value their goodwill over democratic dues (avoiding inheritance taxes, for example). This, the book argues, also gives them a disproportionate voice in public affairs and politics.

In the West, wealthy people attract criticism both when they spend and when they save. Accumulation and compound interest only increase the distance between the rich and the rest. Their position is inherently vulnerable, the book says. Many people already know this. “It’s taxes or pitchforks,” the 2022 Davos Open Letter also acknowledged.

Of the three paths to wealth, finance attracts the most social disapproval. In the mid-20th century, legal regulations were applied to these “money trusts” and inequality decreased, but from the 1980s onwards the pendulum swung back towards finance. Voices of opposition to the oligarchicization of people's lives are once again being heard.

Wealth is now becoming more concentrated, and inheritance and financial assets are exacerbating wealth and income inequality. Apart from direct wealth, a global aristocracy has formed across elite schools and clubs conscious of the common good.

Crises are common, from pandemics to wars, but the wealthy are more reluctant than ever to play their traditional roles. This book asks whether medieval warnings against playing “god among men” come true, reminding us that in Western mythology gods can fall into catastrophe and fall.

Disclaimer

The views expressed above are the author's own.

end of article