Welcome to Up for Debate. Each week, Conor Friedersdorf rounds up timely conversations and solicits reader responses to one thought-provoking question. Later, he publishes some thoughtful replies. Sign up for the newsletter here.

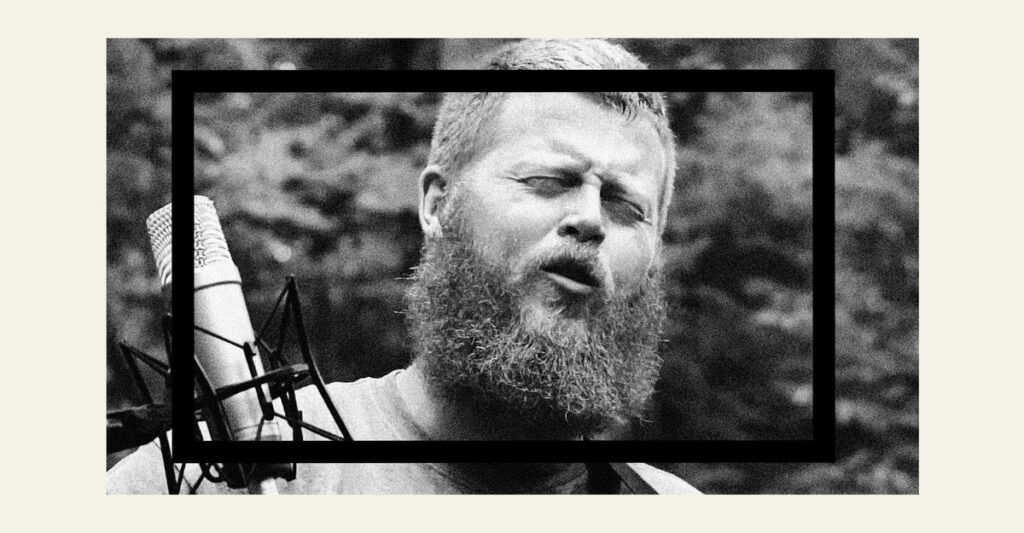

Last week I asked readers to react to the hit song “Rich Men North of Richmond” by Oliver Anthony.

Replies have been edited for length and clarity.

Brian has been fascinated by the music of Appalachia (where Anthony’s grandfather was born and raised) ever since stumbling upon the YouTube channel GemsOnVHS. He argues that divorcing a song from its ethnocultural background is impossible:

The (primarily) Scots-Irish immigrants who populated Greater Appalachia in the 18th century fled a series of disasters caused in no small part by an overreaching, abusive government in the British Isles. The rural, self-sufficient lifestyle many Appalachians maintain isn’t a red hat; it is an effort to distance themselves from the long reach of a federal government that Appalachians have been given every reason to distrust. During the 19th century, Appalachians were split in their allegiances to “North” or “South” because they weren’t fighting the same battle as the Yankees or the Deep Southerners. Appalachians resisted whoever they thought would more meaningfully limit their freedom.

While “Rich Men North of Richmond” is undoubtedly political, and admittedly leans a little to the right, it never registered as overwhelmingly partisan to me. Republicans and Democrats are both to blame for wealth inequality and the inefficiency (or abuses) of some federal programs and policies. There’s no such thing as a one size fits all political classification for the many peoples of Appalachia, and I bet Oliver Anthony isn’t particularly pleased that so many people are trying to speak for him. Last I checked, $300 ties come in both red and blue. Whether it be Puritan proselytizing, a domineering Deep Southern aristocracy, or our modern-day equivalents, Appalachians will be who they want to be, live how they want to live, and fight whoever tries to force them in a different direction. Instead of attempting to claim Anthony’s allegiance, people should quiet down and listen to the words he sings. Millions seem to think they have value.

Abby lives near where the singer performed for the first time since becoming famous:

My family lives less than a mile from Morris Farm Market in Currituck County, North Carolina, and my son was fortunate to meet Oliver Anthony and, more important, experience the concert vibe of the attendees. He’s 23 and is what I’d call conservative-curious. He’s grown up with my center-left ideology and finds that my thinking doesn’t work in all things.

His main impression of the event is that nearly all the attendees related personally with the message but were not overtly advertising any political bias. The crowd was a mix of tourists and locals, which probably diluted our local 85-percent-Republican voting block. His overwhelming impression was that Anthony captured that magic that happens at some shows, where the people and the artist are singing with one voice.

He and I agree that combative left-versus-right battles mainly take place on social-media platforms. Influencers are working overtime to co-opt this song’s popularity to support their own agendas. This does a disservice to Oliver Anthony and his music fans alike by drawing a right/left line in the sand over lyrics that have broad meaning to people.

M.S. has a suggestion for viewing the song through the experience of other people:

Go on YouTube. Search Rich Men North of Richmond reaction videos and tell me this is a GOP song or a white-tropes song. Every person that watches this song LOVES it and relates to it.

At the reader’s suggestion, I watched reaction videos, starting with the first one in my Google search results, and although it isn’t true that everyone loves and relates to the song, the exercise did give useful insight into how many kinds of people are connecting with the song. (Here’s a compilation of positive reactions, and one from a self-described liberal who doesn’t get why so many people regard the song as right-coded. I do see why, but it’s noteworthy that some don’t.)

Jaleelah believes that the song’s success owes a lot to its politics, which she finds flawed:

I like American folk music so much that I listen to it on a daily basis. The respect I have for established (but less popular) folk singers makes me suspicious that Anthony’s rise to popularity can be attributed to his talent or mastery of the genre. Why are Anaïs Mitchell and Bonny Light Horseman not topping the charts? Why have Joanna Newsom’s authentic voice and lyrics (which are more insightful and well constructed than Anthony’s) never propelled her to widespread success? Plenty of folk singers have been making incredible music in the past five and 10 years. Why is Anthony the first to go viral?

“Rich Men North of Richmond” has some aesthetic resonance. Anthony has a unique, appealing voice—it is hollow and grainy; its timbre is hard to train. He has trouble hitting some notes, but that actually contributes to the authentic vibe of the song. The melody is not complicated, but it is compelling. Anthony is a much more talented musician than Jason Aldean. Still, it’s not an amazing song, and political appeal probably plays a bigger role in its success than quality. I think people who hate the government heard that this song gives voice to their grievances and started streaming it to feel validated. To be clear, I don’t think there’s anything wrong with streaming a song because it validates your beliefs. Nor do I think that practice is exclusive to conservatives.

But the political message of the song seems confused. Anthony laments that politicians don’t care about miners—but the average wage for miners and loggers is $38.09 an hour, higher than the average across all private occupations. He laments “bullshit pay,” then complains that the government wants to have “total control.” Does he want the government to legislate higher wages or not? Unions are absent from his song. And many of the rich men keeping wages down (a choice made by corporations, not the government) live south of Richmond.

Sean argues that music criticism is politicized for a reason:

I’m a professor of music and a musician. My doctorate is in classical composition, my bachelor’s degree is in jazz performance, and I grew up going to hardcore/punk/metal shows. A major reason behind the political bent of most of the coverage lies in a major problem within modern music criticism: Most music critics aren’t actually experts in the field. Music criticism, even in well-respected publications, is often written by pop-culture critics as opposed to music-specific critics. This means the authors of most modern music criticism don’t have the knowledge base that is necessary to discuss … well, music.

That’s why so much music criticism, even criticism of non-divisive artists, rests on the narrative arcs of musicians and the place an artist holds within the pop-culture landscape. It’s common to read reviews that only pay lip service to actual musical evaluation, and instead focus on how a song or album fits within the pop-culture climate or where the artist is at in their career. Even within music-focused criticism, a lack of specialization is hurting the effectiveness of the field. One person can rarely speak equally well to the merits of country, hip-hop, rock, pop, classical, jazz, or all the other Western genres, let alone the vast number of folk and classical musics of the entire world.

But that is what is expected of modern music critics. So even people with a deep background in music are almost guaranteed to be writing from a point of ignorance on a regular basis.

There’s nothing inherently wrong with writing about the background of an artist, or how a piece of art fits in our world. The problem is that by focusing criticism through the lens of “pop culture,” meaningful and insightful aesthetic judgment is being neglected. I think that is one of the primary driving factors behind the coverage of “Rich Men North of Richmond.” If a critic can’t effectively criticize the music itself, then their focus must turn elsewhere. In this case, that has meant writing about the political standing of the art and artist.

Denise is reminded of other protest songs:

Woody Guthrie’s “I Ain’t Got No Home” shows us that Anthony isn’t living in such a new world:

I mined in your mines and I gathered in your corn

I been working, mister, since the day I was born

Now I worry all the time like I never did before

’Cause I ain’t got no home in this world anymore.

Now as I look around, it’s mighty plain to see

This world is such a great and a funny place to be

Oh the gamblin’ man is rich an’ the workin’ man is poor

And I ain’t got no home in this world anymore.

No political party can lay claim to the emotions of people who feel that they don’t have a “home” in this country. Both parties fail in meeting the wants and needs of the majority. I’m glad we sometimes luck into hearing talented, independent singers—voices we can appreciate just for their sound and how they express their sentiment, i.e., for artistry. And I’m glad for them that they get discovered. But I think that Woody would tell Oliver that singing about your life isn’t enough and that everyday life is unavoidably political: Yeah, you’ve got a great voice, man, but now suck it up, join a union, and join the chorus. We’ve got work to do. And, oh yeah, please keep on singing. I’d love to see a follow-up story several months from now, to learn how Anthony has dealt with being discovered and whether he feels co-opted.

Andrew dislikes the song’s sociopolitical message:

Oliver Anthony’s ode to victimhood resonates in the current climate, where voices are looking to capitalize on cynicism and hollow rage while listeners are embracing media that discourages personal accountability and nostalgically pines for an era that never existed.

A rejection of the culture of victimhood should be a bipartisan effort. My father, a die-hard Reagan Republican, moved from West Virginia to Florida to take advantage of its opportunities. My wife, solidly liberal, learned a second language, fled the Venezuelan dictatorship, navigated the inhumane labyrinth that is the U.S. immigration system, and found work in a new country. Are we supposed to believe that the “rich men north of Richmond” are preventing rural Americans from driving to a new city 30 minutes away and finding work in the tightest labor market in recent history? There are people immigrating to this country by traversing the Panamanian rainforest for the chance to deliver food, but we’re supposed to feel bad for the guy who refuses to take an air-conditioned bus to the next town over to get a job as a plumber? The American mythos has never been one of victimhood. It’s about taking risks, venturing into the unknown, and building a new life. That so many of us would embrace drinking yourself to death and blaming it on the faceless powers that be is a worrying sign of cultural rot.

Perry has advice for those who relate to the lyrics of the song:

I can understand why a lot of Americans feel this way. My response: There will always be folks with more money. There will always be folks who think they are smarter and better than you. What does that really matter to you? Excel in spite of them. Do what it takes to get where you want to go. STOP WHINING and get to work. Rely on God, family, and friends! YOU ARE WORTH AS MUCH AS ANY OF THEM. I was the 5-foot-8 300-pound father with three boys. I woke up one morning and decided I wanted to see them all married and play with my grandchildren, so I lost 160 pounds. The Rolling Stones said it best: “You can’t always get what you want. But if you try sometime you’ll find you get what you need!”

Sue suggests that following such advice can pay dividends:

Why are jobs that pay good wages and that teach critical skills going unfilled across our country? Is it really that hard to pick oneself up and go to a place where opportunity shines a little brighter? Here is my American story. My husband and I moved from our respective home states and met at college. Between 1970 and 1980, we moved cross-country for his jobs and back to the heartland in pursuit of jobs and education.

Living in the rural Midwest during the early ’80s was hard due to a major recession; however, much of the time I could work overtime in a local factory and bring home bullshit pay. Unlike the person in Mr. Anthony’s song, I was happy being working poor. Evenings were filled with friends, music, and homegrown fun. Plus, I was minimizing my contribution to the wealth accumulation of the military-industrial complex. Nonetheless, at age 35, I looked at myself in the mirror and had a “come to Jesus” talk. So far I had nothing to show for my labor. Less than two hours away was a larger town with better jobs than factory piecework. I got a union job in that town, moved, worked nights while taking classes in a field that promised better pay. Eventually I was well prepared to start a career in my chosen field and found desirable employment in a pleasant location.

Was any of this easy? Not really. Was it quick? No. Did I persevere? Absolutely. In my opinion, Mr. Wright is correct that maintaining a strong sense of my agency in creating my own life is critical to success. Was success guaranteed? No way. I believe that a nontrivial part of my happy American story was due to good fortune in timing of opportunities for my professional growth, coupled with my willingness to engage those opportunities.

Quinn is heartened by the lyrics for political reasons:

As a lifelong liberal, I think the song is encouraging, because he’s talking about economic issues. This is the conversation we want to have and a conversation we can win. He’s expressing genuine and relatable pain; we need to convince him that his prescriptions are wrong. This is the conversation we’ve been winning for decades. Bring it on.

I.L. disagrees:

It’s a song that boldly proclaims that it’s going to take wealthy, powerful people to task but then instead castigates poor welfare recipients and fat people as if they had any power to decide what [the singer’s] tax rates are. Meanwhile, absolutely zero corporations, agribusiness, super PACs, energy companies, or massive retailers are mentioned. It’s a bait and switch—the target audience is buying the switch and forgetting about the bait.

Meredith gives a mixed verdict:

The honesty, restraint, and emotion in Anthony’s voice evoke some of the best folk, country, and blues singers. His voice has a unique timbre that I find hard to describe. At its most emotional, his voice verges on despair; the guitar keeps enough lightness that the feeling doesn’t go over a cliff into complete self-pity. Some of the lyrics aren’t well thought out—and I say that not because I disagree with them but because they distract from the good lyrics.

From my perspective as a socialist feminist, the ideas and opinions that I disagree with are examples of the way in which the capitalist class divides the working class against itself. Anthony simultaneously criticizes capitalism and its hold on both major U.S. political parties, and incorrectly attributes [the narrator’s struggle] in part to taxes that fund public benefits.

All that being said, having now listened to Anthony’s other songs, I enjoy his melodies and his willingness to be vulnerable in his songwriting. He isn’t grandstanding; he is authentic.

And Jonathon believes that country music’s star is rising:

The verses leave much to be desired, but there is no denying that “’cause of rich men north of Richmond” is a brilliant hook. This song’s success is making me reconsider my perceptions of country music. I grew up on it. There was always a sense among fans that country music was countercultural. It fostered the sense of being a cultural underdog, or easily misunderstood or discarded by the cultural powers that be. But take a look at the chart dominance of “Last Night,” by Morgan Wallen, and Luke Combs’s [cover of] “Fast Car.” Jason Aldean’s “Try That in a Small Town” also hit No. 1. Country music is having a moment that is upending some of its assumptions about itself.