Billionaires know they are. Low-wage workers are very well aware that they aren’t. But vast swaths of America’s “regular rich” don’t feel that way, and it’s keeping everybody down.

You know them. They’re lawyers in New York, doctors in Phoenix, dentists in Memphis. They own construction companies in your hometown, burger franchises off the highway, homes in the resort villages your parents want to retire in. They’re young, old, Democrats and Republicans. They have two things in common: They’re rich. But they don’t feel that way.

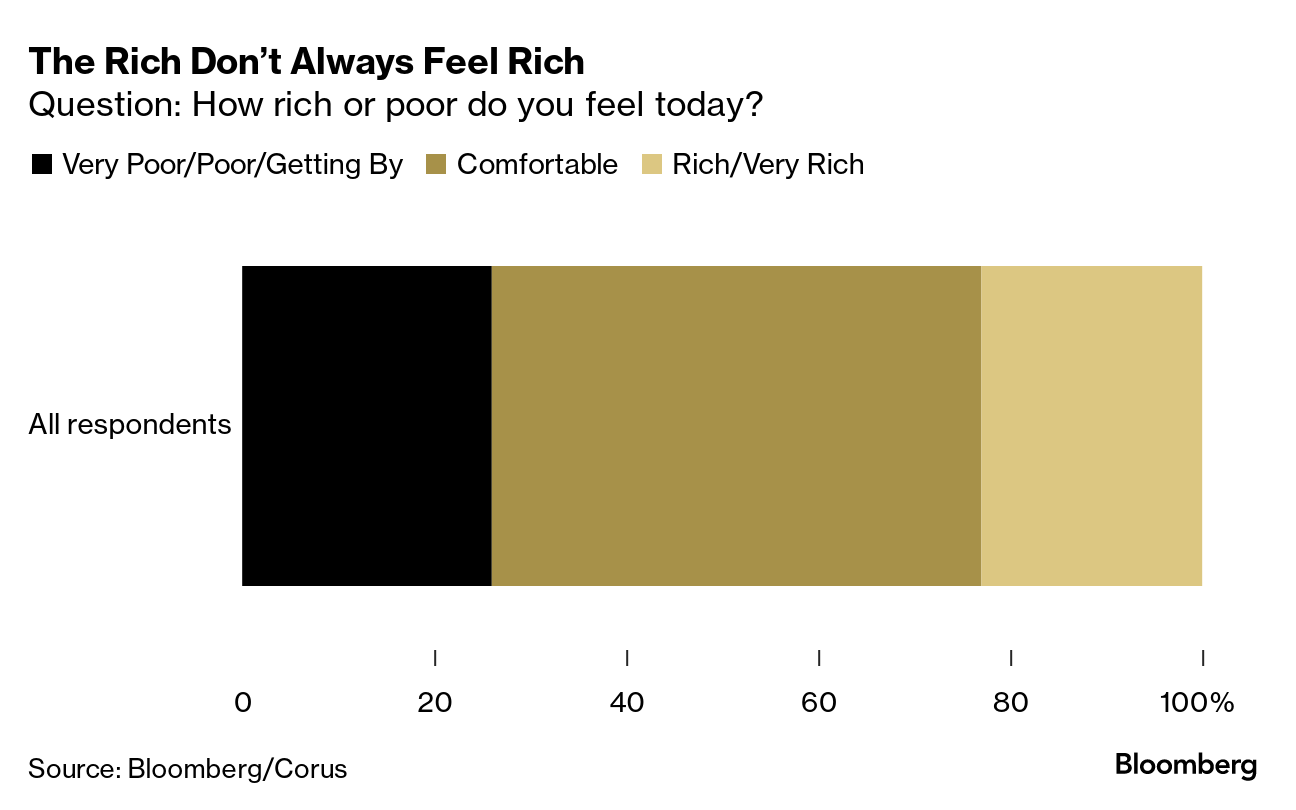

The Rich Don’t Always Feel Rich

Question: How rich or poor do you feel today?

In fact, many even go so far as to say they’re poor. In a nationwide survey of over 1,000 objectively wealthy Americans — defined in this case as making at least $175,000 a year, roughly the amount required to crack the top 10% of US tax filers — a full quarter told us they were either “very poor,” “poor,” or “getting by but things are tight.” Half described themselves as just “comfortable.”

The people we polled have good jobs, own their homes and have savings for retirement. By some combination of hard work and good fortune, they’ve achieved the old-fashioned American Dream. Still, for many it’s not enough.

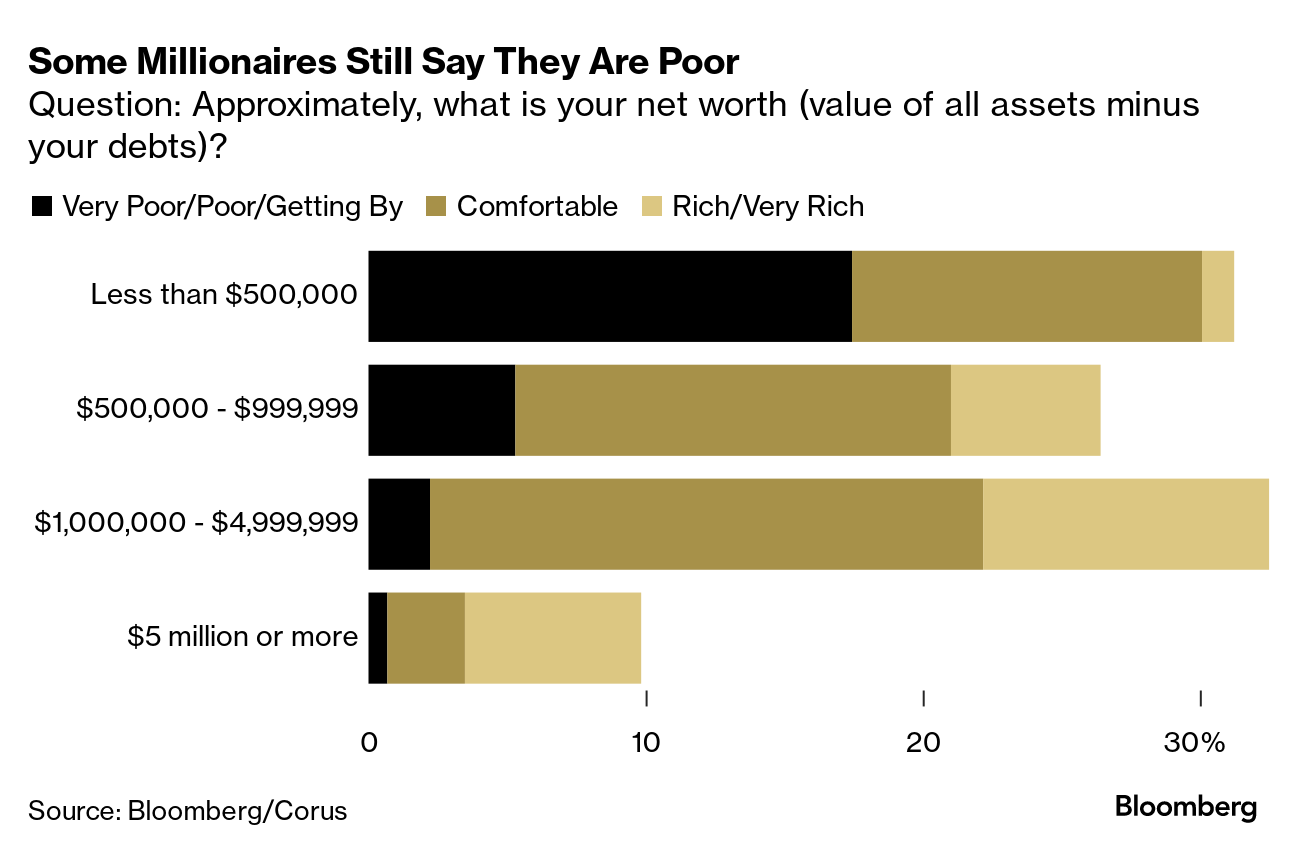

Some Millionaires Still Say They Are Poor

Question: Approximately, what is your net worth (value of all assets minus your debts)?

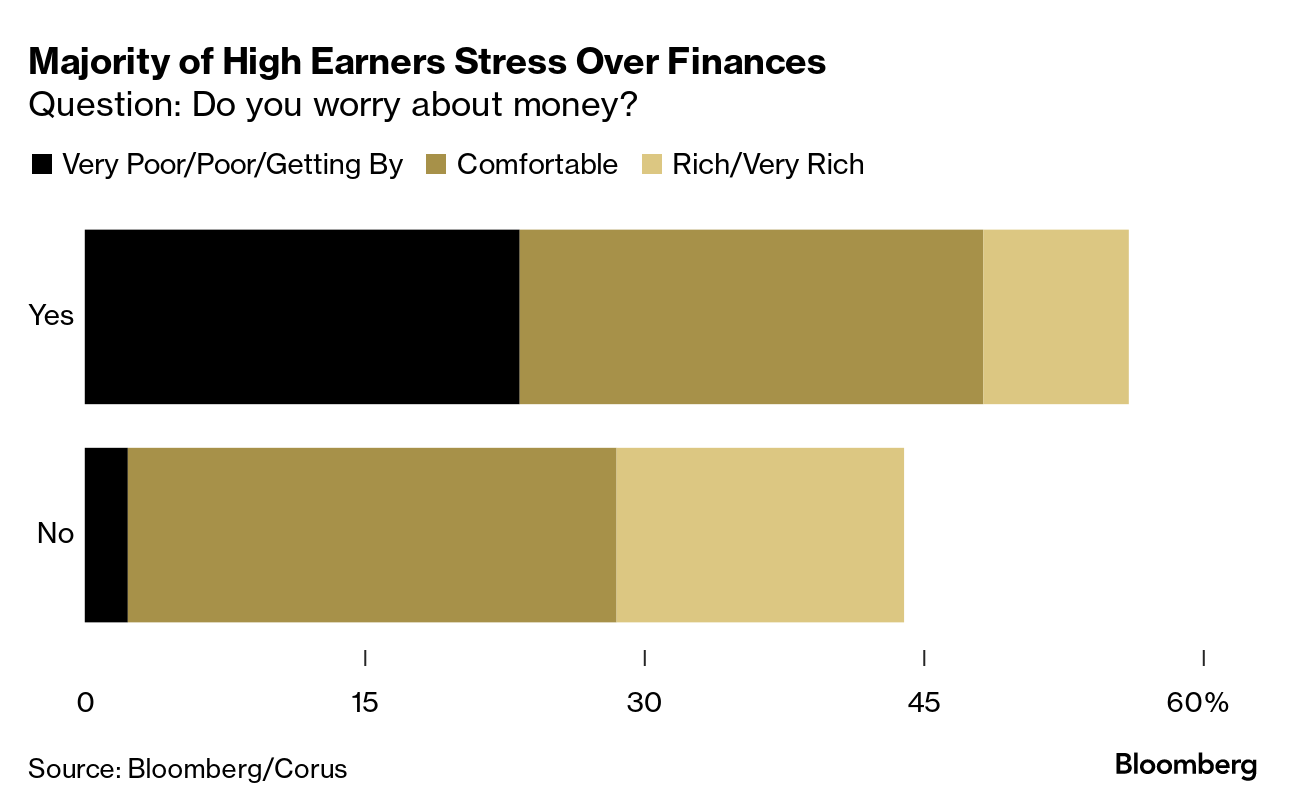

At a time when pretty much everything is more expensive, including cars, tuition, travel and groceries, over half of respondents in our survey said they worry about money. Some 25% don’t think they’ll be better off financially than their parents. And many have considered moving to a different part of the country, joining the pandemic exodus away from high-cost cities to areas of the US with lower taxes and a cheaper cost of living.

Majority of High Earners Stress Over Finances

Question: Do you worry about money?

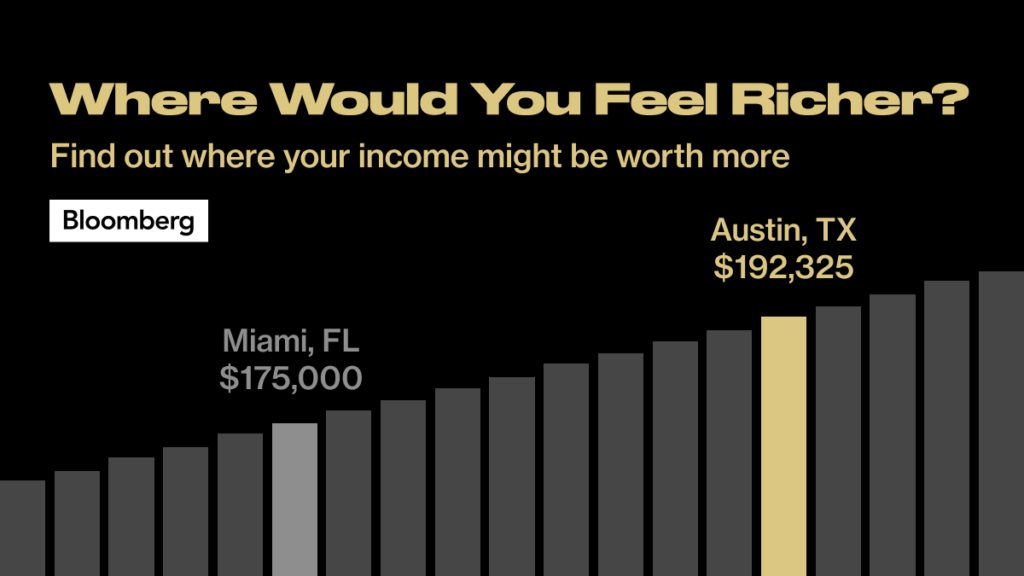

The last few years have seen a once-in-a-generation reckoning in how Americans think about work and where they live, and that of course ties back to how much money they have and how long it will last. To help you understand how your wealth stacks up where you live and how it might look if you decamped to South Carolina, Texas, West Virginia, Florida or other places across the US, we developed a comparison tool.

It uses data from the Census Bureau, covering roughly 85% of the population, to show how much richer or poorer you’d be in a different part of the US. The top salary it measures is $200,000. For more information, see the methodology section.

The dissatisfaction of the mass affluent might seem like a rich person’s problem, but it hints at a potential breakdown at the heart of American capitalism. Much has been written about the end of upward mobility in the US and how hard it is these days to build wealth. But if those who have actually made it don’t feel like they have, where does that leave the rest of us?

Want to go even deeper? Our WealthScore tool shows a full breakdown of how your finances stack up to help you get ahead.

Social media makes it easier than ever before to compare your lifestyle with those of your neighbors, celebrities, professional athletes or friends from college on the other side of the US. It’s a daily bombardment — private jets, lavish trips, fancy meals, home renovations and other flashy displays of conspicuous consumption. With a few clicks, it’s easy to be left feeling like you don’t have enough, especially at the time when the ultra-wealthy have accumulated more and more money and there’s a growing sense that more and more people are getting left behind.

To understand the large and growing class of “regular rich” people, we polled hundreds of them and interviewed dozens in extensive conversations covering everything from their incomes and net worth to their thoughts on relocating to cheaper parts of the US. The goal was to understand why so many with so much feel poor. And what it all means.

The most revealing thing that happens when you ask someone the question “Are you rich?” is not necessarily the “yes” or the “no” but the more detailed answers that immediately follow.

“I still worry about money,” said Debra Corbin, a 67-year-old retiree in Naples, Florida, with a home worth more than $1.3 million. “I think rich is subjective. When I’m in southern Illinois where we’re from I feel rich. When I’m in Naples, I feel blessed. Down here it’s hard to feel rich because there are billionaires down here.”

“I grew up quite poor, and I know money can be taken away,” said James Bramble, a 53-year-old attorney in Salt Lake City who makes about $350,000 a year. “To really feel rich that I think you would no longer have to depend on money — like if you didn’t work, you’d still be okay for the rest of your life, and I’m not there.”

“To feel rich, I would have to own my house free and clear without mortgage, pay for my kid through college and have more liquid cash in the bank,” said Erika Wilson, 45, who has a household income in the “low six figures” and lives in Durham, North Carolina. “I worry about future expenses and increasing inflation.”

Here’s a fuller look at what people told us when we asked them a simple, but fundamental question: Are you rich?

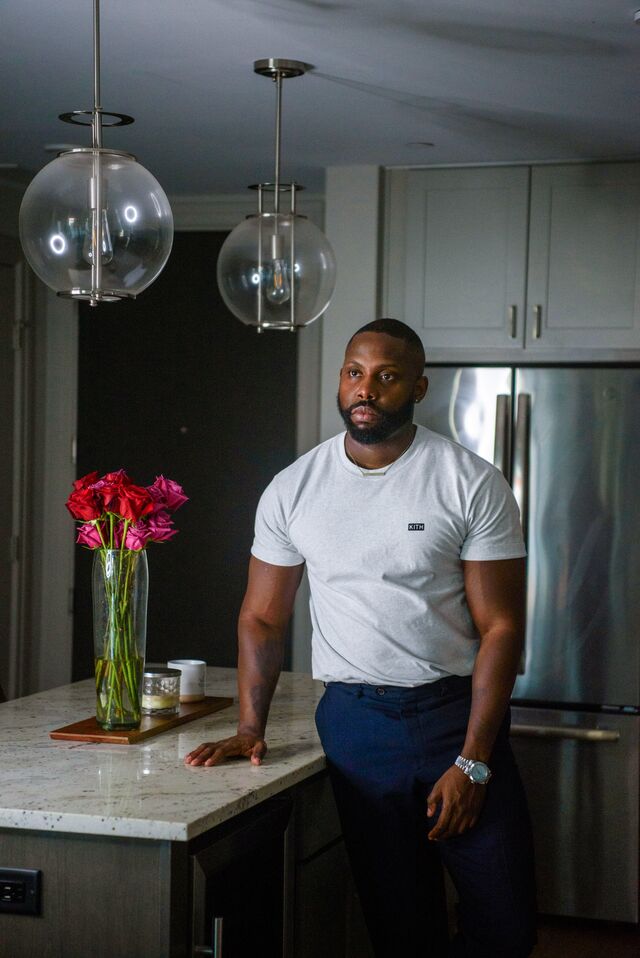

Tiouba ParrisAdvertising Account DirectorHouston, Texas Photographer: Callaghan O’Hare/Bloomberg

Tiouba Parris spent most of his life in New York City, but then joined the flock of people who moved to Texas during the pandemic. The 33-year-old had built a successful advertising career in Manhattan but felt like his annual salary of $160,000 wasn’t going very far.

“I was making good money, but it didn’t feel that way in New York,” he said. “I wanted to move somewhere I could make the most of my finances.”

In April 2022, he decamped to Houston where he can get a 1,000-square foot apartment in a luxury building for just $2,700 a month— much more space than his New York place and $300 cheaper.

Plus, he loves the lack of income taxes in Texas. He got to keep his New York salary when he moved, so he’s suddenly getting a bigger chunk of take-home pay. Everything is also cheaper in Texas, he said, especially restaurant meals and alcohol. He’s aiming to buy a house in 2025, after the real estate market hopefully cools.

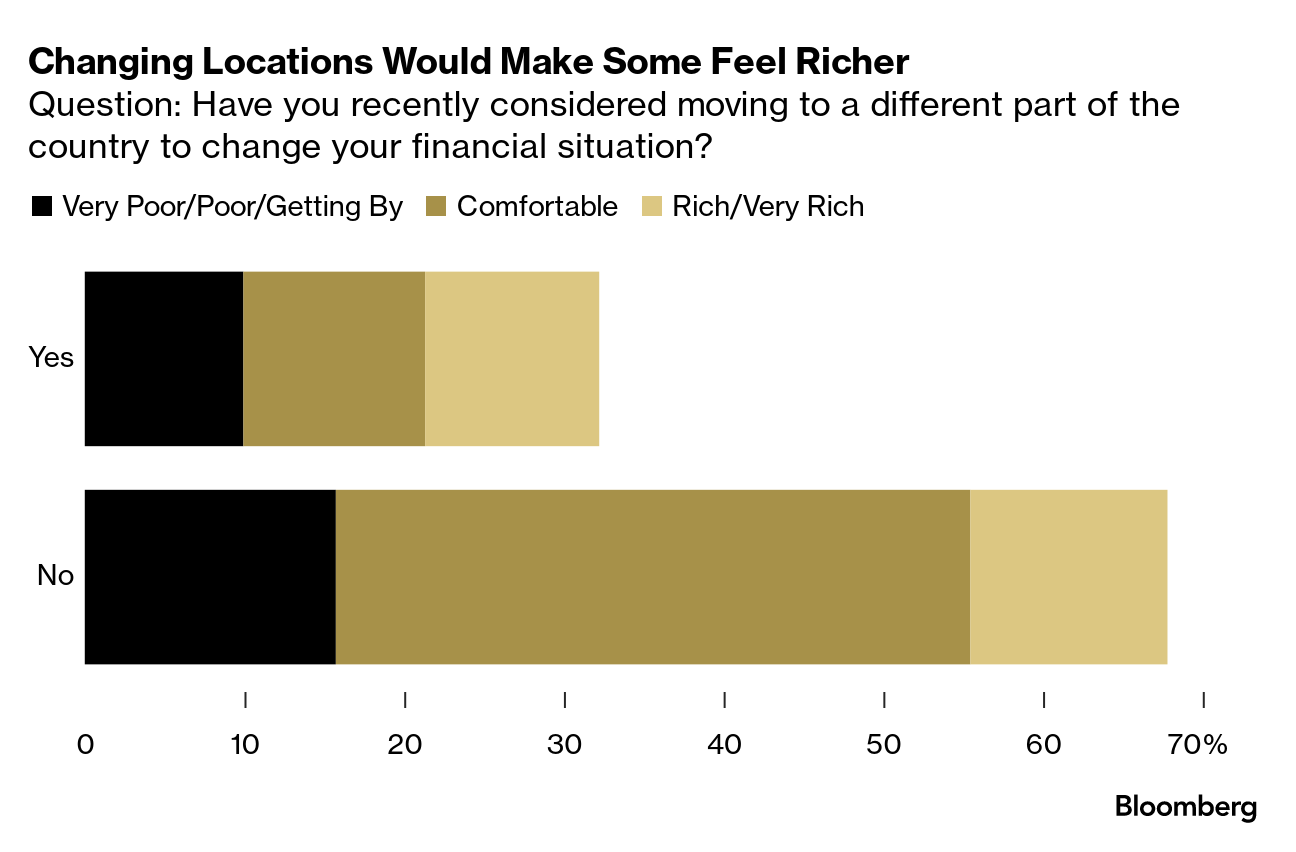

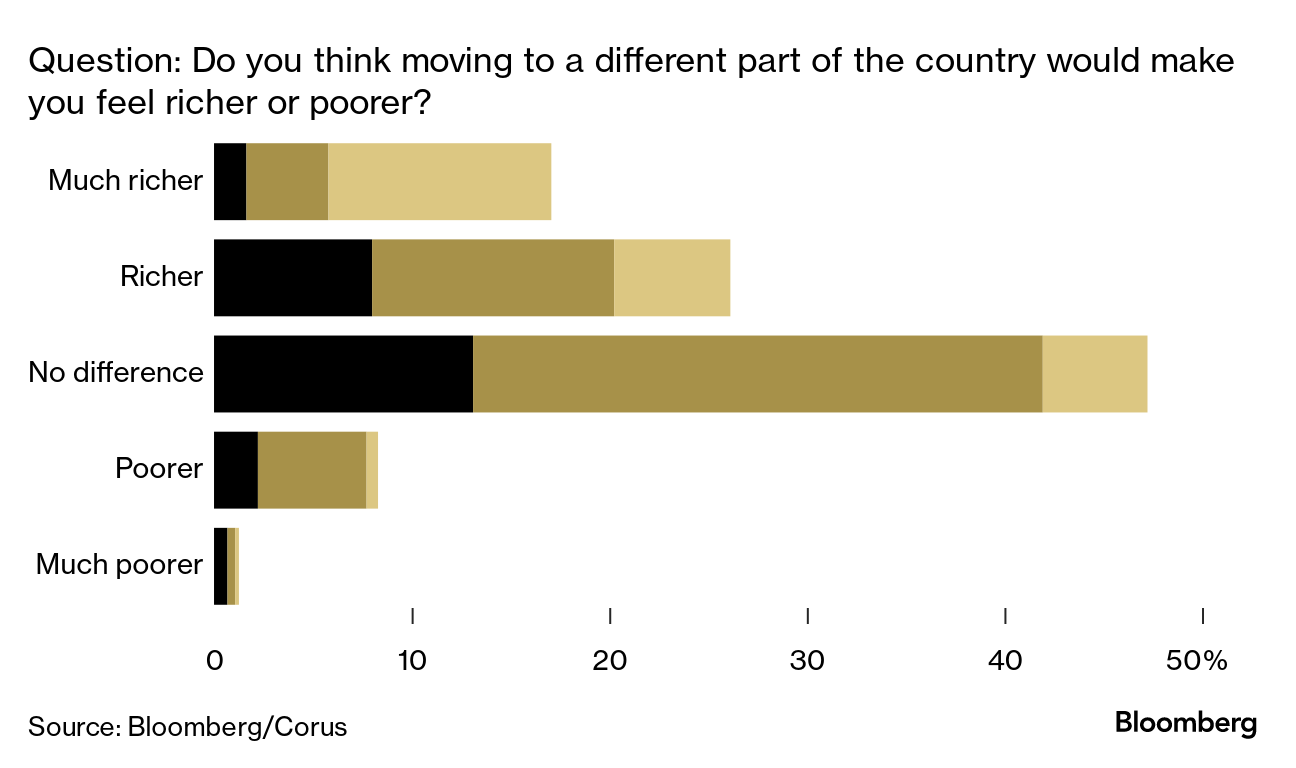

Changing Locations Would Make Some Feel Richer

Question: Have you recently considered moving to a different part of the country to change your financial situation?

Question: Do you think moving to a different part of the country would make you feel richer or poorer?

Still, he worries about money and definitely doesn’t feel rich.

“Ten years ago if I had told myself I was making the money I am now, I’d be flabbergasted. I would’ve said I was living it up,” he said. “Now, while I’m financially secure, it doesn’t feel like I’m making the dollar amount I’m making.”

Parris started a sneaker cleaning company as a side hustle, which nets him about $10,000 in profits a year. He has about $10,000 in emergency savings, a 401(k) and sneaker collection worth about $30,000, but he knows that wouldn’t get him very far if he lost his job, especially with an $850 monthly payment for his private student loans and the lifestyle creep that inevitably accompanies a six-figure salary.

“Honestly the more money you make, the more your lifestyle kind of changes a lot,” he said. “Your vacations and the restaurants you go to are more expensive.”

Jennifer NguyenStock Plan AdministratorHuntington Beach, California Photographer: Alisha Jucevic/Bloomberg

Before having kids, Jennifer Nguyen never worried about money. Now the 36-year-old mom to a toddler and a newborn, who lives in Huntington Beach, California, is constantly stressed about finances — daycare bills, future education costs, buying clothes and food for her growing family.

This is despite making good money. She works as a stock plan analyst and her husband is a computer programmer, making about $300,000 a year combined, far more than the average American. Their home, bought in 2012 for about $400,000, is now worth more than $1 million.

Yet rising prices have her concerned about the future, especially in her area.

“It just seems like everything is just getting more expensive,” she said. “We’re comfortable now, but what about when my kids go to college? And before that, do I have enough to put them in daycare? Do I want to have a nanny?”

Getting laid off last year — she’s since found another job — made her realize how precarious her financial situation truly is.

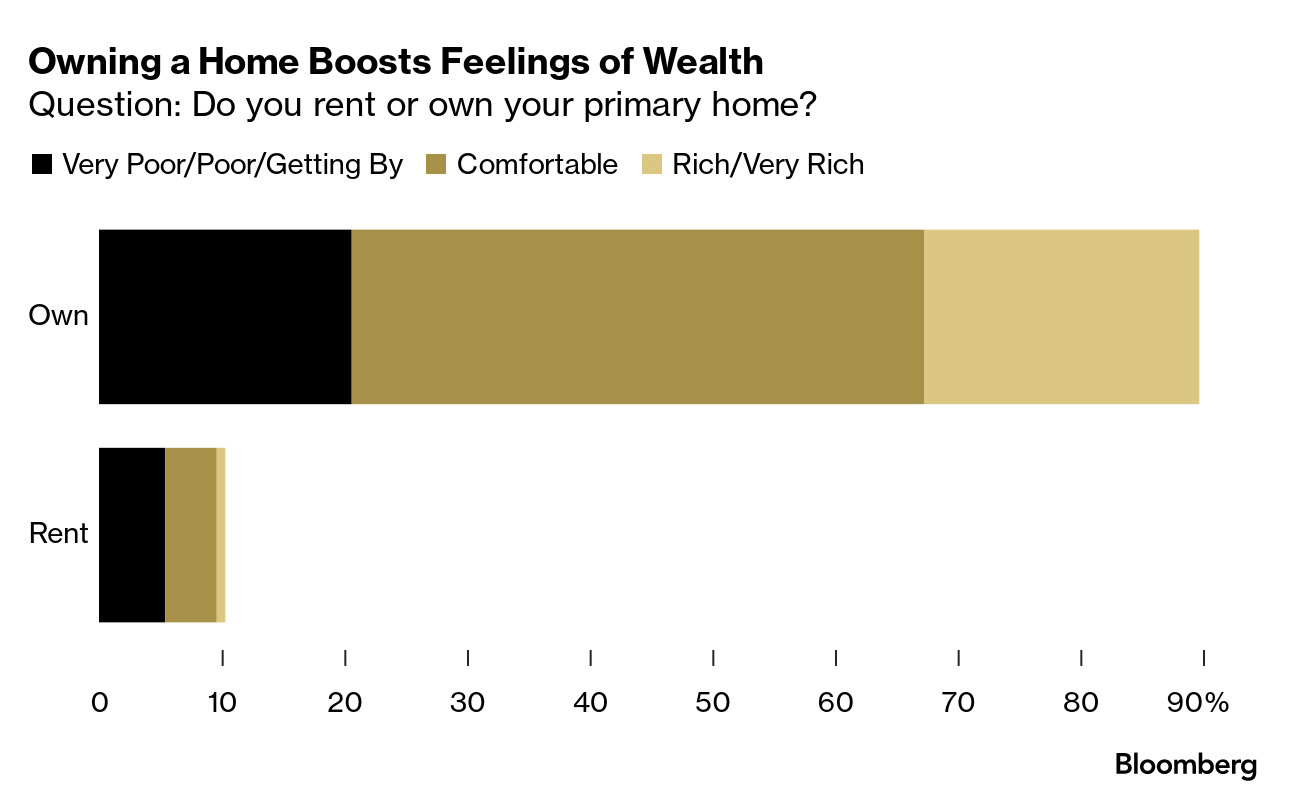

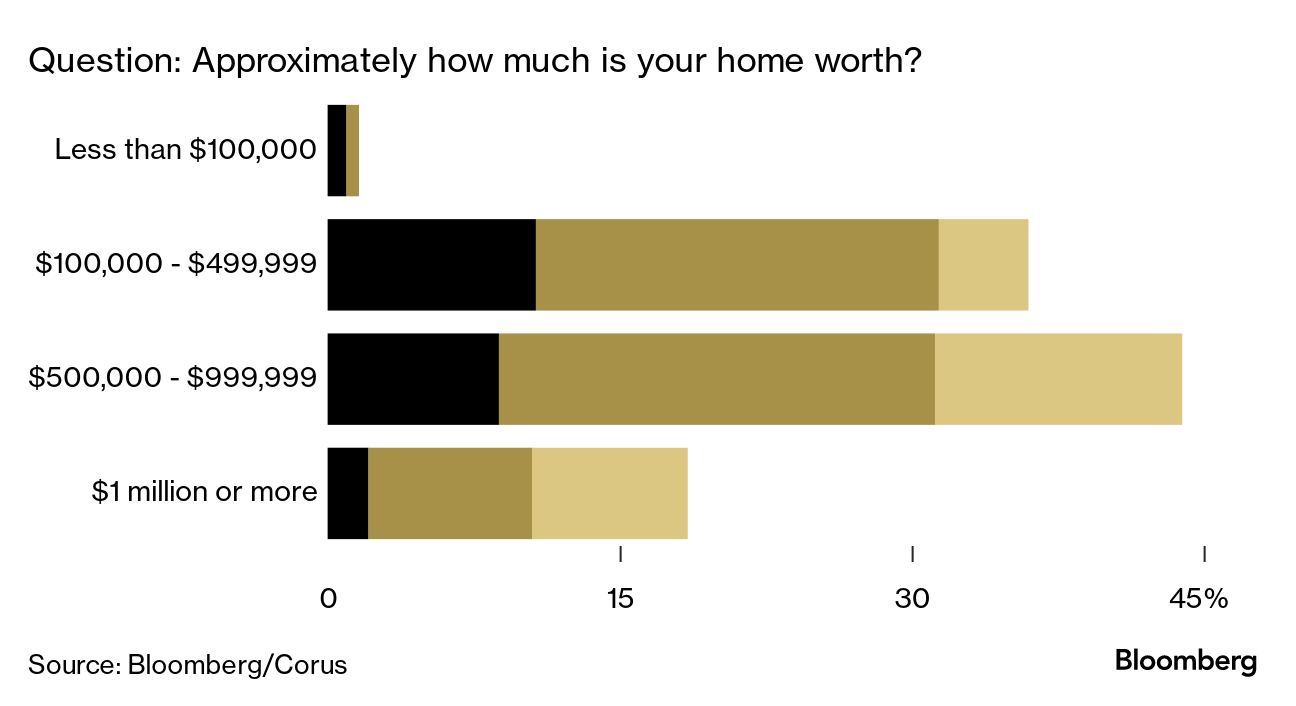

Owning a Home Boosts Feelings of Wealth

Question: Do you rent or own your primary home?

Question: Approximately how much is your home worth?

“Now that we have kids, I want to give them the biggest financial cushion I possibly can,” she said. “If that means a lower-cost-of living area, that might require moving out of state.”

She’s talked to her husband about relocating to Texas, attracted in part by the lack of income tax, but they have lots of family in California, which would make it harder to leave.

Jane Edwards

Banking Consultant

Brooklyn, New York

New York City resident Jane Edwards, 55, has one word to describe the state of her finances: “terrible.” She makes about $180,000 a year as a banking consultant on Wall Street, but that doesn’t go very far, especially given inflation in recent years, she said. She currently doesn’t have any retirement savings, after losing a lot of it in the 2008 financial crisis and then cashing in the rest of her 401(k) in subsequent years to pay her bills.

“I know it sounds like a lot of money, but it’s just not in New York,” she said about her salary.

Edwards is currently about $10,000 behind on rent and can’t afford health care as a freelancer. She used to pay as much as $4,000 a month in rent, but she recently found an apartment in Bushwick for $1,200, which she’s hoping will help her financial situation. She’s considered moving out of New York to Florida or the West Coast, but after her husband died a couple years ago, she’s been relying on friends in the area for support and is reluctant to give that up.

“I’m just broke all the time,” she said. “I was never rich before but I was able to pay my bills. Since the pandemic, everything has gotten more and more expensive.”

Mary PhippsRetired PharmacistSt. Cloud, Minnesota Photographer: Nicole Neri/Bloomberg

After a long career as a pharmacist, Mary Phipps finally feels rich. The 66-year-old who lives in St. Cloud, Minnesota, never made a crazy amount of money — about $200,000 a year before she retired about a year ago — but it was more than enough to raise five kids with her husband, a freelance artist who is also now retired. Their home, bought for about $179,000 in 1999, is now worth more than $370,000 and completely paid off.

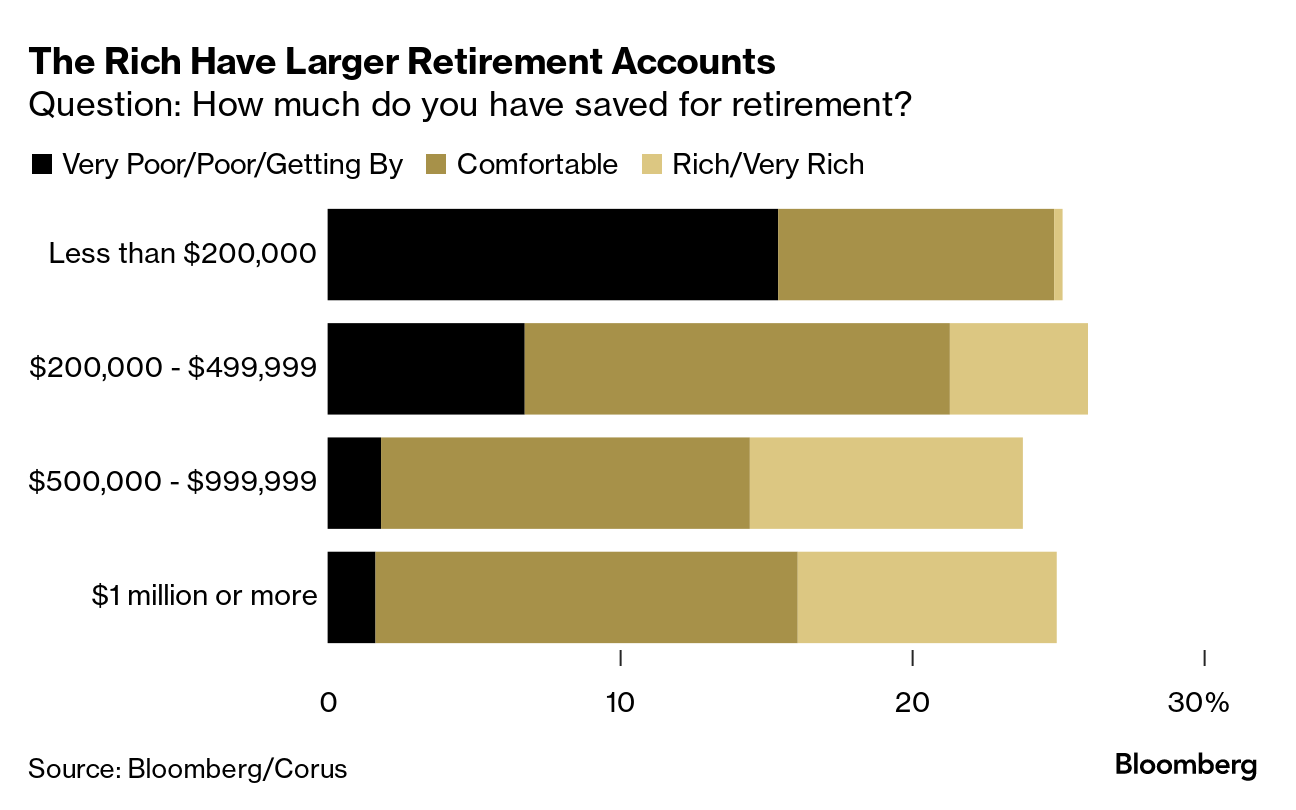

The Rich Have Larger Retirement Accounts

Question: How much do you have saved for retirement?

With a healthy retirement account and social security checks arriving for both her and her husband each month, their income now is about $14,000 a month before taxes, more than enough to live on. Right now, she’s financially secure.

“We like to travel a couple times a year and overall we’re able to do what we want,” she said. “We don’t spend as much as we did now that our kids are grown and college is done.”

Raised by parents who lived through the Great Depression, she can’t help but worry a bit about money, and Minnesota’s relatively high state tax doesn’t help.

“I know we’re not going to run out of money, but maybe that’s just the way I was brought up.” she said.

Tom ThompsonConsumer Behavior AnalystDallas, Texas Photographer: Shelby Tauber/Bloomberg

Despite owning a home worth almost $400,000 in Dallas and a condo in Hawaii, Tom Thompson and his wife don’t feel rich. In fact, having more money has just resulted in more bills. The 54-year-old is feeling the pressure of inflation, especially as he prepares to pay for his 18-year-old son’s college tuition.

Despite an annual household income of about $450,000, Thompson worries about his job stability at an ad agency where losing a big client could mean a layoff.

“We’re not living paycheck to paycheck, but I feel like we have looming expenses,” he said. “My personal definition of rich is the ability to buy or participate without concern, and I do not have that.”

His bills keep adding up: $2,800 a month for his mortgage on the Dallas home, $1,400 a month for the Hawaii condo, three car payments, and soon his son’s $25,000 yearly tuition. His salary isn’t keeping up.

“I know we do very well, but I didn’t get a raise and neither did my wife since before the pandemic,” he said. “That’s starting to impact that feeling of wealth.”

He and his wife, who works as a consultant on employee benefit plans, have considered moving to a cheaper area like New Hampshire or even overseas to Amsterdam. But he’s hesitant to give up the 2.2% mortgage rate on his home, so for now, he’s staying in Texas.