MEXICO CITY — Giovani Tovar left Venezuela five years ago in search of work after the country collapsed under President Nicolas Maduro's watch. He now sells empanadas and tequeños on the streets of Peru's capital, where he keeps pushing a small cart equipped with a deep fryer.

Tovar wants nothing more than to vote for Maduro to step down. He sees an opportunity for change in July's long-awaited presidential election, but he won't be able to vote. Neither do millions of other Venezuelan immigrants, due to costly and time-consuming government prerequisites that are nowhere to be found in Venezuela's electoral law.

“I really don't understand why they would put so many obstacles in the way of us exercising our vote,” Tovar said, before stating the main reason he suspects immigration is behind the prerequisites. “I really want to vote, but I don’t want to vote” for Maduro. ”

More than half of the estimated 7.7 million Venezuelans who left their homeland during the complex crisis that characterized Maduro's 11 years in office are estimated to be registered to vote in Venezuela. But only about 107,000 Venezuelans scattered around the world, including those who emigrated before the crisis, are registered to vote outside South America, according to government figures.

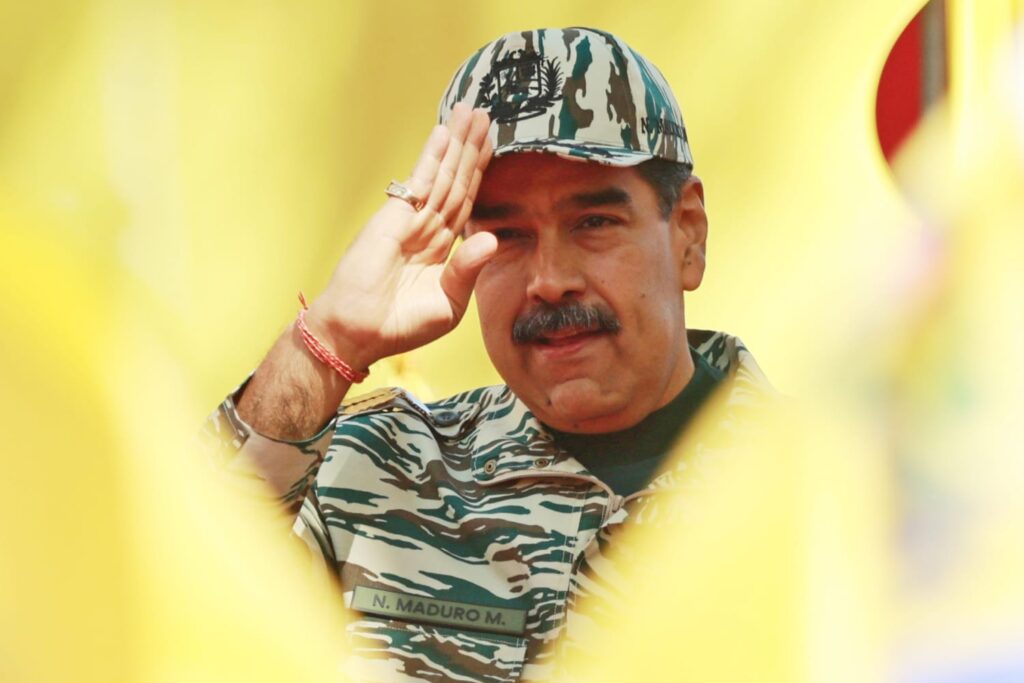

Analysts and migrants say those who left Venezuela during the crisis would almost certainly vote against Maduro if given the chance. Maduro, who took over as interim president in 2013 after the death of hotshot Hugo Chávez, is seeking his third term in office.

Venezuelan law contemplates absentee voting, allowing citizens to vote at embassies and consulates. Interested voters must be properly registered with a foreign address and cannot be illegally present in the host country or seek refugee or asylum status there.

Since the majority of immigrants do not have legal status, the residency requirement alone significantly reduces the number of people who can register. During this year's registration period, which ends on Tuesday, even people who have been granted temporary residence in their host countries are being turned away by consular officials as diplomatic missions abroad require proof of permanent residency.

According to a flyer outside Colombia's consulate general, a “permanent residence certificate issued by the host country” must have a “validity date of at least three years from now” and “must have been issued at least one year ago.” must be stated. The capital, Bogotá. However, Venezuela's electoral law only requires interested voters to “possess the right of residence or other qualifications indicating the legality of their stay” in a foreign country.

Peru granted Tovar temporary rather than permanent residency.

Further complicating matters for some concerned voters is the requirement to possess a Venezuelan passport, which is prohibitively expensive and currently takes weeks to months to process. It takes.

Maria Cordova and her family, who immigrated to Mexico 18 years ago, participated in October's presidential primaries for a U.S.-backed opposition party. The election was organized by a commission independent of the National Electoral Council, which is loyal to Venezuela's ruling party. The commission allowed interested voters like those in Córdoba to register to vote online, and ultimately more than 200,000 people registered worldwide.

When voting time arrived, Cordova traveled from Cancun to Mexico City, where preliminary organizers set up a voting center. Cordoba now hopes to vote against Maduro on July 28, but has not yet received the passport he has been trying to renew since last year.

“This is an ulterior plan because you have to pay a fee to apply,” she said, referring to the passport renewal process.

Opinion polls show Venezuelans overwhelmingly want to vote and would defeat Maduro if given the chance.

According to official estimates, about 36,000 of the 107,000 Venezuelans who are properly registered to vote abroad live in the United States, but they face insurmountable obstacles. The consulate where people normally vote has been closed because Venezuela and the United States severed diplomatic relations after President Maduro was re-elected in 2018.

The contest was widely considered fraudulent, and Mr. Maduro was ostracized. Hopes for a more democratic presidential election were briefly raised in October when President Maduro and opposition parties supporting the primaries agreed to cooperate on electoral terms that would level the playing field.

Among the issues the two countries were expected to address was updating the country's voting rolls. However, Maduro's government has blocked opposition figure Maria Colina Machado, who won the primary election, from running for president, and arrested some of its staff, violating the spirit, if not the letter, of the agreement. This and other changes never materialized because they started to contradict each other. A criminal investigation will be launched against the main organizers.

Christopher Sabatini, a researcher at London's Chatham House, said that while opposition parties may complain about the obstacles faced by migrants, they could prioritize encouraging votes abroad given the challenges they still face at home. He said that the gender is low.

“There are still many adult people in Venezuela who have never voted before. Bringing these people into the democratic movement is kind of a priority for the opposition,” Sabatini said.

Most people who left Venezuela in the past decade settled in other countries in Latin America and the Caribbean. Colombia is home to the largest group of them, with more than 2.8 million people living across the country.

One of the main barriers faced by local Venezuelans is that consular officials accept temporary protection permits (documents issued by the Colombian government that give access to health care, education, and jobs) as legal proof. It is refusing to do so. situation.

Nicole García, a Venezuelan and member of the grassroots group Venezuelans in Barranquilla, said the demand for documents, which most migrants do not have, is a way for the consulate general to try to limit participation and transparency in elections. said.

“Consular staff are people who are part of the government or part of the regime,” she said.