In an August 2000 letter to children's book and comics scholar Philip Nel, cartoonist Sid Hoff detailed his history with the left. Nell was writing a book about comic book creator Crockett Johnson. burnaby Manga and Harold and the purple crayon. During the 1930s, Johnson was an art editor. new massa left-wing magazine to which Hof contributed comics.

However, Hof new yorker and children's book author danny and the dinosaur, and was doing so under a false name. in his work, new mass, he used the name A. Redfield. According to Hoff, Clarence Hathaway came up with the pen name when he hired Hoff as a cartoonist for a publication he was editing. day laborer. Hathaway was a member of the Communist Party and rose to prominence within the organization along with Earl Browder, who eventually became general secretary. day laborer It was the party's house organ. The existence of pen names among contributors was not unheard of. Amid the ever-present threat of Red Scare, some artists kept their connections to the left secret.

That distance turned out to be wise for Hof. In fact, the FBI called him in his 1950s. In a 1952 statement to the agency, Hoff downplayed the caricature he drew as A. Redfield and his own staff position at the agency. day laborer.

“My involvement with the 'day laborers' and the 'new masses', the Young Communist League, the American Alliance Against War and Fascism, was all based on…what they actually represented. “Because of my lack of knowledge and experience with the group,” he wrote, claiming he couldn't remember the names of the people he knew at the time (aside from Hathaway and another member, Russell Limbach). day laborer The name on the masthead would have already been known to the FBI). “I do not, and never have, supported the doctrines of communism,” he wrote.

For many who experienced this fear, it never seemed to die completely. As Hof wrote to Nell in his 2000, “These statements should not be printed, because they would ruin me as a 'children's writer'!” Please refrain. please! ”

In his foreword to the New York Review Books reprint, Nell spoke of the reality of Hof's relationship with the left. ruler's claws (Hathaway also came up with that title), a collection of Hoff's comics. day laborer The truth was that the Bronx-born Hoff dropped out of school at age 15, painted billboards for a while, and then entered the National Academy of Design at the urging of his taxi-driver brother. There, a classmate introduced him to the communist movement.

During the Great Depression, Hof moved closer to the left. He was arrested during a picket of the Cartoonists Guild. “We sang 'Eternal Solidarity' in our cells.” He joined the John Reed Club, an organization of communists and fellow travelers, and attended the Communist Party-affiliated Camp Unity (racial integrated) summer resort. At the latter, he met the poet and songwriter Abel Melopol, who would later write “Strange Fruit.'' In 1933 he day laborer.

The works he created do not feel 90 years old. If it weren't for Hoff's attire of the representatives of the ruling class (full tuxedos, modest gowns for the women) and his tendency to depict the wealthy as almost uniformly overweight, his illustrations would be modern. It might have become. America. After all, our era has a lot in common with the era of “A.” Redfield’s”: spectacular inequality, rampant homelessness and police brutality, racism, and many arrogant and foolish industry leaders.

The Hof's rich people are a pathetic bunch. “Good! Good! Good! So how are the Wall Street titans today?” In one illustration, a physically imposing personal trainer asks a shrimp-like client. “Yes, sweetheart, I believe fascism is coming,” a man tells his wife while reading a newspaper in another cartoon. “Oh, my!” she replied, “And this is a maid's night out!”

In yet another photo, a young bourgeois in a tuxedo, holding a glass of champagne, laments his date. “Daddy says that if I get expelled from another university, he will be put in charge of one of the factories.'' In another, an old capitalist shows off with a cologne and a flower in his buttonhole, only for the object of his desire, a maid, to walk unnoticed by him.

These people think of themselves as paternalistic towards the army of workers, but they are not so similar as giant infants.

These industry giants are also vindictive and stingy, but it's no use. In many cases, they simply inherited their wealth.

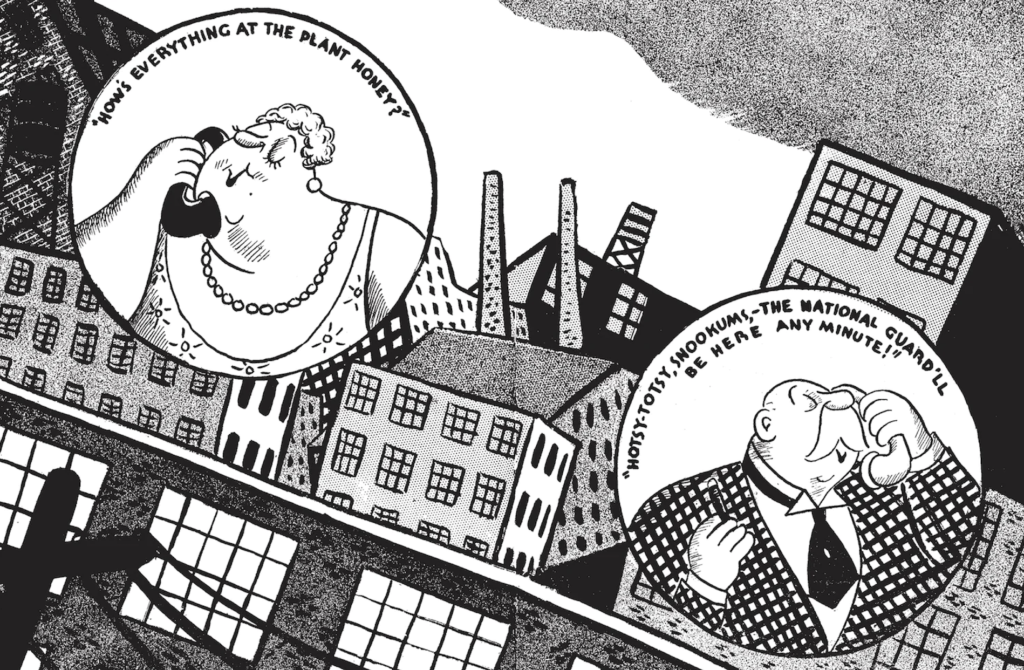

A small boy scolds the butler, “How many phone calls do you have to make!'' A boss stands on stage in front of a room of employees at a rally organized to promote the company's union. He rattles on about “we who turn the wheels of industry,” but the workers stare back with cold faces. One of the women, wearing pearls and sitting on a couch, says to the other, “I'm against unemployment insurance, because it makes people lazy.”

These capitalists are a bunch living a delusion. They are protected from the world by shelters such as mansions, guards, and servants. “I'm not afraid of anything!'' One general told another, never mind that he was not one of the soldiers who had to risk his life in the war.

The Hoff's wealthy are completely out of touch. If they were not responsible for so much suffering, they would be pathetic figures. Women are primarily concerned with their pets and wardrobe. “I can't wait for another war,'' some people say to friends through cards. “I had so much fun knitting socks and bandaging them last time.'' “Don't be silly!'' the woman says to the beggar. “Everyone knows the recession is over!”

It all sounds true. When I meet rich people, they always talk about themselves, and on rare occasions they even seem like they're talking about something bigger. When the world has little to disturb your home sphere, your interests tend to focus on yourself, that is.

It all creates a very boring environment. Unless you abhor hardship, you can observe that people who have alleviated all hardships with huge sums of money tend to be less amused. They have little experience so they have nothing to say.

Hof depicts a young bourgeois couple strolling through a park and encountering a homeless man sleeping on a bench. “I wish my mother would let me live like that for six months so I could write a novel,'' a man tells his date.

In the original 1935 preface, ruler's claws, day laborer Writer Robert Forsyth (Kyle Crichton's pen name) says that Hoff was not fueled by hatred of the “heavily battered women” and their capitalist husbands depicted in the comics, but rather something else. He writes that he was driven by something.

“It would be extremely foolish for a seemingly decent person like Redfield to waste his good anger on these fundamentally donkey people,” he wrote. “Obviously what's driving him is a sense of relief, gratitude, and a sense of superiority. Most of the time, it's superiority.”

Such superiority, or arrogance, on the part of the working class, Forsyth writes, “is always a source of great concern to the upper classes.” He continues: “Acting on the assumption that excellence in their lives is a condition to be envied by the rest of the world, workers, especially revolutionary artists, do not see themselves as objects of envy; I'm always dissatisfied with what people think of me.It's a very comically important subject.

No matter how much money you have, people don't become cool. Elon Musk's life is proof of that. It is clear that Hoff also viewed the rich in this way. Yes, they were class enemies and caused serious harm to the working class and the planet, but they were fundamentally beneath him and his fellow workers and were not worthy of hatred. There wasn't. Ninety years later, the clowning of Mr. Musk and many of his wealthy ilk is helping to revive this view of the wealthy. If there's one thing I can be thankful for to those people, it's that. Sid Hoff may be long gone, but A. Redfield's spirit should live on.