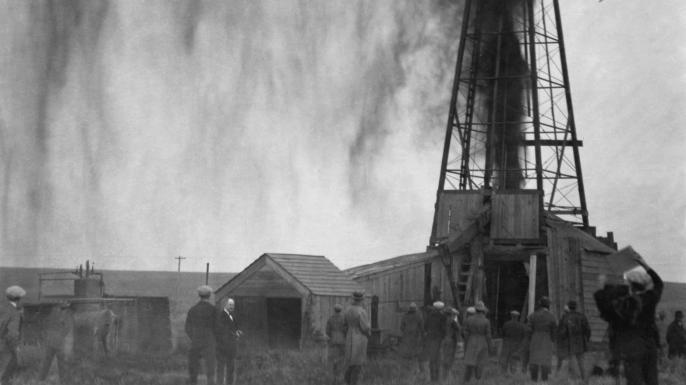

Throughout the 1920s, an epidemic of murders and mysterious deaths terrorized the Osage Indians of northern Oklahoma. After oil began to well up on their tribe's land decades ago, white wealth seekers descended on Osage territory in droves, seizing their property and figuring out how to exploit their vast oil wealth. looked for. The most ruthless ones approached their victims, gained their trust through marriage or guardianship, and then extorted their victims' money or even became parties to their murders.

8 Amazing Inventions of Native Americans

Osage wealth sparks 'reign of terror'

In the early 1920s, the Osage Indians were the wealthiest people on earth per capita. According to the book's author, journalist David Grann, Murders of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI, Oil leases paid the Osage nation more than $30 million in 1923 alone (the equivalent of more than $400 million today). The tribe divided the royalties equally among its thousands of enrolled members, whose shares were known as “headlights.”

Headship could not be bought or sold, but could only be inherited, so outsiders had to marry into the Osage family or become their legal guardians. In northern Oklahoma, intermarriage between whites and Native Americans increased dramatically, an unusual occurrence in a country where European settlers had historically treated Native Americans with cruelty and prejudice.

And after the federal government passed a 1921 law requiring Osage members to prove financial “competence” or be assigned financial guardians, lawyers flooded into the area, serving diligently and scooping up money. did. A 1924 investigation by the Indian Rights Association, a policy and advocacy group founded by non-Indians, estimated that the guardians stole at least $8 million directly from the Osage Ward's restricted accounts, which they called “requisitions.” and an orgy of exploitation.”

Most disturbingly, wealthy Osage people were being found dead one after another. From 1907 to his 1923 alone, they died at more than 1.5 times his national rate, author Dennis McAuliffe calculates. The Death of Sybil Bolton: Oil, Greed, and Murder on the Osage Reservation.

It differs from the family murder and subsequent conviction chronicled in Gran's book and dramatized in Martin Scorsese's film. Murderers of the Flower Moon, many similar Osage murders were never investigated or prosecuted. Researchers and tribal officials say the reasons are widespread apathy, corruption and collusion by local white officials.

Police investigations, if they did occur, often blamed the victim, wrote McAuliffe, a former lawyer. washington post journalist. Intentional poisoning is said to be caused by drinking bad alcohol. The shooting was deemed a suicide. His autopsy was often omitted, his burial hurried, and his death certificate falsified. Such was the case with his grandmother, whose mysterious death served as the inspiration for his book.

As for how many Osage people were killed during what came to be known as the “Reign of Terror,” the Fed's official tally ranges from a low of 24 (based on a limited investigation by the Bureau of Investigation) to a high of several hundred. Estimates vary widely. Some, like Osage Nation and National Archives historian Jesse Kratz, estimate the number to be about 60. “The true number may never be known,” McAuliffe wrote. However, according to his calculations, even by conservative estimates, the Osage were not only the wealthiest people per capita at the time, but also the most murdered.

marriage strategy

Molly Burkhart (right) and sisters Anna (center) and Minnie (left). (Credit: David Grann)

The tribe's oil wealth attracted hordes of white suitors seeking marriage. According to McAuliffe, “Osage single women were the subject of hot pursuit,” resulting in a “flood” of letters to the Osage Agency seeking invisible, oil-rich brides. CT Primer of Joplin, Missouri, wrote a typical letter. “I… want a good Indian woman as my wife…for every $5,000 she's worth, I'll give you $25.” If she's worth $25,000, if I get her. , you will receive her $125. ”

According to Gran, one white woman who was married to an Osage man told a reporter how local residents conspired openly. They owned all the officials… They had an understanding of each other. They said cruelly, “You take so-and-so, so-and-so, and I'll take this.'' They brought the Indians with full rights and large farms. I chose it. ”

From 1918 to 1923, Molly Burkhardt's family was murdered one after another, but given her husband Ernest's complicity, it was a horrific case of marital greed and malice. Her mother, her three sisters, her brother-in-law, and a cousin all died at that time by bullets, bombing, or possible poisoning. Molly and her son narrowly escape when her sister's house explodes. Several concerned white locals who had promised to seek help from federal authorities also died, including one thrown from a train and another brutally murdered outside a pool hall in Washington, D.C.

Molly was the only survivor of the family and became the holder of the rights to the head. As she grieves and seeks answers, her husband Ernest, prompted by her scheming uncle and assisted by two unscrupulous doctors, administers her daily insulin injections. Slowly they began to poison it with poison.

The Bureau of Investigation (later renamed the FBI) finally began an investigation and succeeded in unraveling a huge murder conspiracy. In the center stood Ernest Burkhardt's uncle, William K. Hale, a prominent land magnate. Investigations show that the man who described himself as a pillar of the community and a “best friend” of the Osage family secretly hired his nephew and others to execute Molly's relatives and colluded extensively with local authorities over the years. and covered up the incident. He and Burckhardt received life sentences. Both were eventually released on parole.

guardianship strategy

Another way for outsiders to gain access to Osage Money was to secure an appointment as financial guardian. While some administrators were sincerely trying to help their wards overcome the challenges of sudden large amounts of wealth, many were taking advantage of it. According to a 1924 Indian Rights Association report, wealthy Indians in Oklahoma were robbed “in a scientific and ruthless manner, shamelessly and openly.” The conservatorship system was steeped in corruption, and many of the charges were “plums handed out to the judges' loyal friends as rewards for their support at the polls,” the newspaper claimed. In 1924, the Department of the Interior indicted 20 Osage County attorneys and guardians on corruption charges. All cases were resolved by petition.

In an interview with history.com, former Osage chief Jim Gray, a direct descendant of Molly's murdered cousin Henry Roan Horse, says the conservation law was designed to take away the Osage's right to self-governance. “This was a product of policies at the time that stripped the Osage of their right to do whatever they wanted with their money. [And] If you were an Osage woman, you didn't even have any more political rights than a man. ”

Skimming money turned out to be a common strategy, McAuliffe writes. For example, in 1925, quarterly headlight payments averaged $3,350. However, Restricted Osages (those deemed “incompetent” and subject to guardianship) were given $1,000, with the rest pocketed by the guardian. A 1924 report found that parents used other methods, such as withholding funds for necessities, charging exorbitant fees, and receiving kickbacks from sellers of prohibitively expensive goods. But it details story after story of people fleeing from the natives.

But government records suggest an even more sinister act. While researching the Reign of Terror, Grann discovered the Bureau of Indian Affairs journals listing the Osage guardians and their wards at the time, and noted whether the guardians died under their care. One administrator, whose wards included Molly's mother and sister Anna, caused the deaths of seven Osage wards while managing the money. In another patient he had 8 of his 11 wards die, and in another patient he had more than half of his 13 wards die. “The numbers were astonishing and clearly exceeded natural mortality rates,” Gran wrote.

In his book, McAuliffe investigates the death of his grandmother, Sybil Bolton. McAuliffe was shot in the chest in broad daylight while playing with his 16-month-old daughter (McAuliffe's mother) in front of the AT home of his stepfather and guardian. Woodward. Mr. McAuliffe uses the FBI's Osage files, extensive investigative reports and personal family records to present solid evidence that discredits the official determination of suicide as the cause of death. He concluded that she was likely shot and killed by Woodward himself, who discovered the financial wrongdoing. Bureau of Indian Affairs records reveal that Woodward had four other wards, Gran wrote. All four also died under his watch.

Intergenerational trauma caused by the Reign of Terror

McAuliffe shares the experiences of many Osage descendants who have lost family members. They have lived in a nagging certainty of crime, unable to find justice due to non-existent or fabricated records, and a persistent family lie. Both victims and perpetrators were related, and some grew up hearing contradictory stories of their deaths. McAuliffe's mother, who was raised by her white father and stepmother after Sybil Bolton's death, had long been told that her healthy 21-year-old mother had died of kidney disease. McAuliffe writes that when she learned the truth in her 60s, it forever changed her world and the world of her children.

Ora Mae Levard Davis was just two years old when her young Osage mother died in 1918. Since then, Ola Mae has suffered neglect and abuse from those who were supposed to protect and care for her, said her granddaughter, Olivia Gray, who works for Osage Citizens. She fights to recognize the epidemic of missing and murdered Indigenous women.

Abandoned by their white father, Ola Mae and her younger brother were raised by their Osage grandparents. When they died, their white grandmother placed them in an orphanage in Texas, Gray said. history.com“so [the white father and his family] We will be able to retrieve their leader. ''On one splurge, Gray says, her grandmother asked for $20,000 for her furniture alone (the equivalent of about $307,000 today).

Ten years later, their father adopted them from the orphanage, but Gray says it wasn't out of kindness. He and his new white wife were living on his deceased wife's allotment, but the tribe threatened to isolate him and asked about his children. “That's when they went to pick up my grandmother and her brother from the orphanage,” Gray says. “No one loved them.”

Ola Mae, who inherited her headship at the age of two, married her court-appointed guardian, Frank Simpson, at the age of thirteen. “She was probably the closest person to her,” Gray says. She had always thought so highly of him, but she was the victim. ”

“He was her guardian, so he controlled her money and all her affairs,” Gray says. “I can't say enough good things about it.”