by Elia Ben-Ari

A new type of targeted immunotherapy drug shrinks tumors in about one in three patients with small cell lung cancer (SCLC), the most aggressive type of lung cancer, according to results from a clinical trial. Experts say the findings are encouraging, as little progress has been made in treating advanced SCLC.

Most patients with SCLC respond to initial treatment with chemotherapy and immunotherapy. However, despite additional treatment, the cancer usually progresses, and most of these patients die within weeks or months.

The early-stage clinical trial tested two doses of an experimental drug called talutamab in patients with SCLC whose cancer had progressed after at least two lines of treatment — many of whom had already received at least three lines of treatment.

In the trial, tumors shrank in 40 percent of people who received 10 mg of talutamab every two weeks, and in about 32 percent of people who received 100 mg.

Additionally, in more than half of all patients whose tumors shrank with tarlatamab, the treatment suppressed cancer development for at least six months, and in many patients it was maintained for more than nine months.

This last finding is particularly noteworthy, said Dr. Anish Thomas of the NCI Cancer Research Center. The doctor studies SCLC but was not involved in this trial.

“This is probably one of the most promising therapies currently being tested for small cell lung cancer,” said Dr. Thomas. The new discovery offers hope to patients and those who treat them, he continued, “particularly because this disease is so aggressive and there have been few treatment advances since the 1980s.”

The results of the trial, known as DeLLphi-301 and funded by Amgen, which makes tarlatamab, were presented on October 20 at the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) annual meeting in Madrid, the same day. New England Medical Journal (NEJM).

The new study results “support the use of tarlatamab in these previously treated patients,” said Luis, MD, PhD, lead investigator of the trial at Madrid's University Hospital in October 2012, who presented the results at the ESMO conference.・Paz Ares said.

The results are “encouraging,” agreed Pilar Garrido, MD, of Ramon y Cajal University Hospital in Madrid, who spoke about the trial at the ESMO congress but was not involved in it. But she noted that patients needed to be hospitalized to manage serious side effects the first time they received the drug, which poses logistical challenges to its use.

Dr. Garrido also noted the need for more data on the efficacy of talutamab in SCLC that has spread to the brain, as well as biomarkers that can predict which patients will respond to the drug.

Dr. Pazuarez said the drug's manufacturer has already begun a large clinical trial comparing tarlatamab with standard chemotherapy in patients whose SCLC has relapsed after one initial treatment.

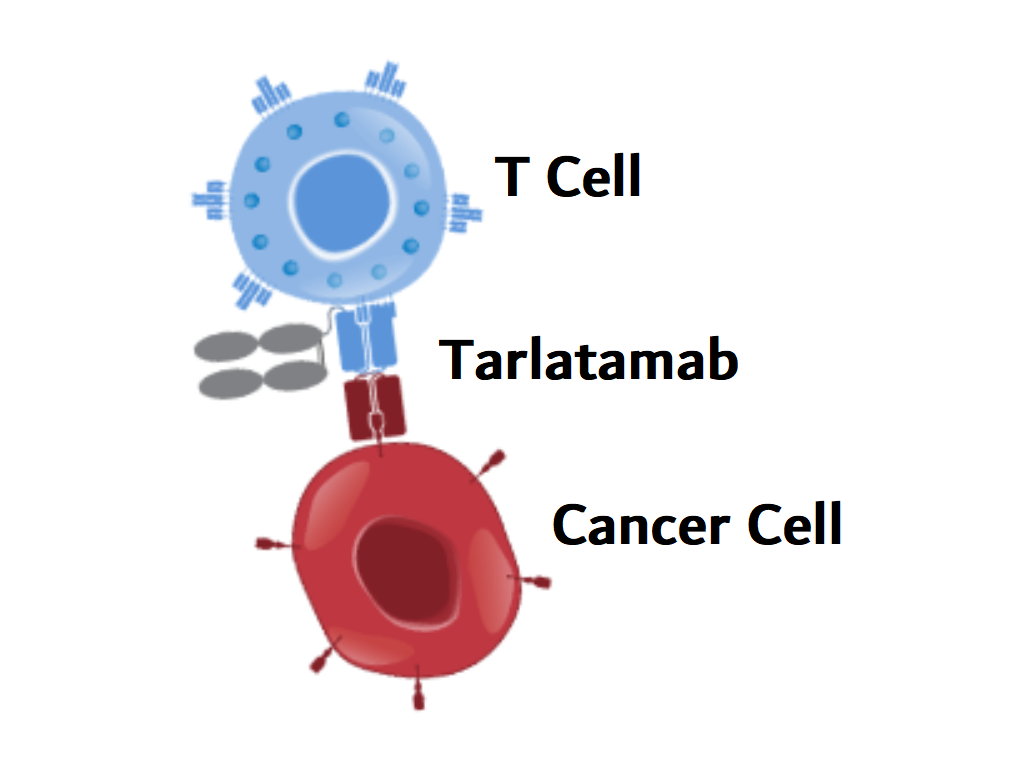

Tarlatamab uses T cells to destroy small cell lung cancer cells

Tarlatamab is a type of immunotherapy known as bispecific T-cell engager (BiTE). These two-armed drugs simultaneously attach to tumor cells and immune cells called T cells. By bringing T cells and cancer cells closer together, it helps T cells recognize and destroy cancer cells.

The arm of tarlatamab, which targets small cell lung cancer cells, binds to a protein called DLL3. Although this protein is normally found intracellularly, it is often present at high levels on the surface of SCLC cells and is recognized by tarlatamab.

That makes DLL3 a “very attractive target in SCLC,” Dr. Garrido said.

The trial enrolled more than 200 patients with advanced or extensive-stage SCLC that had progressed or was no longer responding to treatment. All participants had received previous chemotherapy, and many had also been treated with a different type of immunotherapy drug, an immune checkpoint inhibitor. All participants had received at least two previous treatments, and one-third had received three or more.

The research team analyzed responses to tarlatamab in 100 participants who received 10 mg of tarlatamab intravenously every two weeks and another 88 participants who received 100 mg every two weeks. An additional 34 patients who received 10 mg were included in the analysis of side effects.

The 40% response rate (tumor shrinkage) seen in the 10 mg group was “far superior” to the 15% response rate previously seen in patients receiving standard treatment for relapsed SCLC, Paz said. Dr. Ares and his colleagues write: NEJM.

What's more, in 30 percent of patients who responded to the drug, the response lasted for at least nine months. This finding is “intriguing,” Dr. Thomas said, because cancer typically grows very quickly.

Patients in the 10-mg group survived a median of 14.3 months after starting tarlatamab, compared with 6 to 12 months with current treatment. The researchers are still following study participants to learn more about tarlatamab's side effects and its effect on lifespan.

Based on the early results of DeLLphi-301, future clinical trials will likely use a lower dose (10 mg) of talutamab, Dr. Pasuares said.

Common and Potentially Serious Side Effects of Tarlatamab

Tarlatamab's side effects are generally “manageable,” Paz-Ales said, with only about 3% of patients in the study discontinuing treatment altogether due to side effects. Additionally, 13% of the 10 mg group and 29% of the 100 mg group had to temporarily discontinue treatment, reduce their dose, or both due to side effects.

The most common side effect of tarlatamab was cytokine release syndrome, a potentially life-threatening reaction in which inflammation spreads throughout the body. Other common side effects included loss of appetite, fever, and anemia.

About one-third of patients experienced side effects, including severe cytokine release syndrome. Severe side effects occurred more frequently in patients who received higher doses of talutamab.

Most cases of cytokine release syndrome are “manageable and are usually treated with supportive care such as intravenous fluids and medications to reduce fever and inflammation,” Dr. Passarez said. However, one patient in the 10 mg group died from treatment-induced respiratory failure.

Another potentially serious side effect of tarlatamab is ICANS (immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome), which includes a number of neurological effects such as severe confusion, impaired attention, tremors, and muscle weakness. It will be. ICANS were more common in patients in the 100 mg treatment group, with one patient in each dose group discontinuing treatment completely.

Both ICANS and cytokine release syndrome are commonly seen with other immunotherapies that activate T cells to kill cancer cells, such as BiTE and CAR T cell therapies.

Challenges, concerns and questions remain

Dr. Thomas noted that the trial was not designed to compare tarlatamab with standard treatment for SCLC. “But we have solid historical data on how quickly the disease progresses with standard treatments.”

Another problem, he said, is that current practice requires that all patients with advanced SCLC be treated with chemotherapy and immune checkpoint inhibitors at the time of diagnosis. However, about one in four participants in this trial had not received treatment with an immune checkpoint inhibitor. Therefore, it would be useful to know how effective tarlatamab is in people whose cancer has returned despite previous immunotherapy, he explained.

Possible side effects are also a concern. There were few serious cases of cytokine release syndrome in the trial, and most occurred after the first or second dose of tarlatamab. Still, patients were required to stay in the hospital for a few days as a precaution while receiving their first few infusions of tarlatamab, so the potential risk of side effects from early dosing is “an important consideration,” Dr. Thomas said.

Additionally, people need to be in generally good health to take part in clinical trials, and potentially serious side effects could be more severe in people who are in poorer health, he continued.

For all these reasons, it's important to know “how to best manage side effects so that patients don't have to be hospitalized, how to predict, prevent and treat them,” Dr. Thomas said.

They also noted that some patients died within six weeks of starting treatment, before the research team could assess whether the deaths were due to worsening of the cancer. “We need to better understand whether these early deaths are due to side effects.”

Finally, Dr. Garrido said another challenge is to identify biomarkers that can predict which patients are most likely to respond to tarlatamab. The researchers focused on DLL3 on tumor cells as a potential biomarker, but whether a person responds to the drug does not seem to be related to the presence or absence of DLL3 in the tumor, the researchers reported. .

“Despite many challenges, these results give new hope to patients,” Dr. Garrido said.